I joined the UP Open University as a faculty member in 2001, six years after the university was established and six years since I left the teaching profession. Joining UPOU was my return to the academe. After graduating from college, I immediately taught undergraduate courses at another constituent unit of the University of the Philippines (UP). After a three-year teaching stint, I worked in research and development in a couple of development organizations for a few years. UPOU, being an open university but still part of UP, was both familiar and strange. The emphasis on academic excellence and academic freedom was evident but I also felt that it was more open in many ways.

Obviously, the mode of teaching and learning took into consideration the students’ context. I understood that distance education was designed to help students who for one reason or another cannot study in the conventional educational system. I was also unaware that our students are mostly professionals and may have different goals than the full-time graduate students I have encountered in my graduate studies.

Being a teacher at UPOU was quite novel to me. Having been educated in the traditional system, I had some questions and doubts: Will my students actually learn? Is it possible to teach with minimal interactions between and among my students? Will I actually thrive in this environment? Just as I had concerns, I also believed that education should be made more accessible and equitable. I was also drawn to the fact that as UPOU teachers, we were exposed to a variety of tasks including curriculum development, course writing, production of audio-visual materials, and the like. To prepare us for these roles, the university provided various training programs to its faculty members. Things were moving fast. We had to learn fast.

Over the years, advancements in web-based technologies have altered the way we teach at the university. My exposure to other schools of thought in my discipline has widened my idea of what my students should learn. As the university underwent organizational changes, so did our institutional practices. This is a narrative (Stanley, 1993) of my shifting identities as a teacher at UPOU.

“Online tutoring is more difficult than I initially expected. While certain behavior and teaching styles in face-to-face tutoring also apply in the online setup, the absence of social cues and the asynchronous mode of communication call for a different approach. The fact that this is all taking place in a distance education mode adds another dimension to the teaching context.”

These statements were articulated in a paper that I presented in a national e-learning conference in 2002. A year earlier, I joined the UPOU as a faculty member. In the first term of my work in the university, I primarily taught through the course manuals written by other authors and the monthly face-to-face tutorials conducted at the Learning Centers. Student attendance to these tutorials was optional.

A term later, the university decided to introduce online learning into the teaching and learning mix. Monthly face-to-face tutorials were still available but online tutorials were also offered for the first time. A Learning Management System was put in place for discussion forums, submission of assignments, and emailing of students.

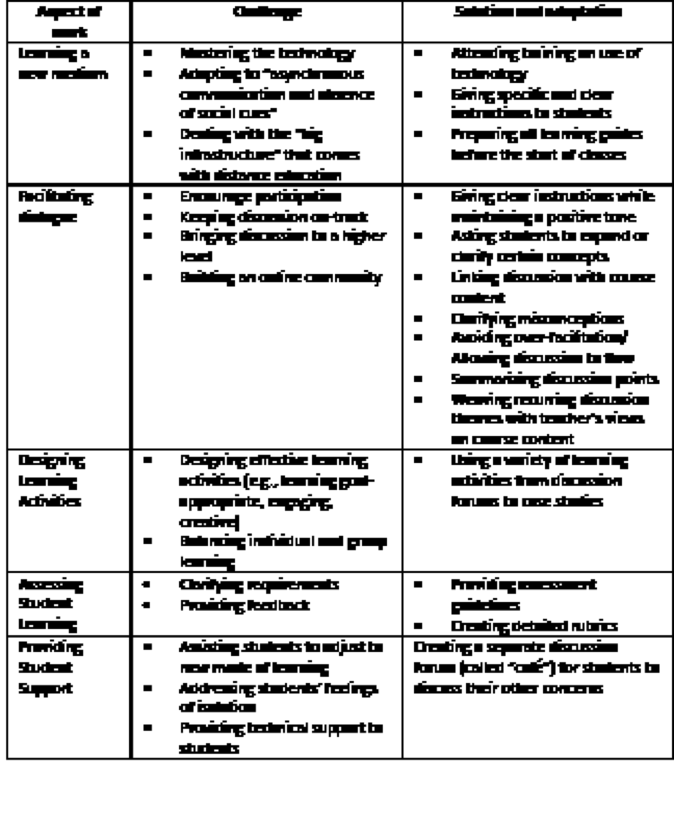

As a novice online teacher, I faced a number of challenges (see Table 1) that shaped the way I saw myself as an academic—both as a teacher and a researcher. Having previously taught in a conventional campus, my experience as a teacher has mainly revolved around delivering content (i.e., lecturing). Learning activities such as class discussions and examinations were basically there to test my students’ mastery of content I transmitted. Upon entering the UPOU, my role as a source of knowledge was transformed to that of a “guide on the side.” I came to the university at the tail-end of a distance education mode that is heavily focused on the use of carefully prepared print modules. Regular training programs were conducted to teach content experts to design and write course modules. These materials were subjected to the review of a quality assurance team composed of the author, an instructional designer, a reader, a media specialist, and a language editor. The modules are supposed to be written in a conversational manner and “talk” to the learners. At that time, it is not unusual to hear the phrase “the module is the teacher.” As a Faculty-in-Charge (as the teachers are called in UPOU), my function was to assist the students understand the modules and acquire mastery of the concepts and other skills through the learning activities designed by the course author.

At first, my interaction with my students was limited to the monthly face-to-face study sessions. In addition to handling one class, I was also supervising two other tutors for the two other sections in the introductory postgraduate course I was handling. In our tutors training, we were reminded not to do “lectures” at the study sessions, which must be supposedly spent on clarifying concepts that students find incomprehensible, addressing learner difficulties, and conducting learning activities to deepen students’ understanding of the content. Tutorials fell under the jurisdiction of a student support services unit, which also took care of tutors training and the collection and distribution of assignments from the students to the tutors.

The move to online tutorials has retained the centrality of the printed modules in the teaching and learning process but has opened up more spaces for interaction between and among my students and myself. Students who cannot attend the face-to-face study sessions now have another opportunity to participate in the discussions. The virtual classroom has enabled me to engage with my students more frequently. However, it also brought a number of challenges, particularly in the areas of learning a new medium, facilitating dialogue, designing learning activities, assessing student learning, and providing support in the online environment (Table 1).

Table 1. Challenges experienced as an online teacher and the solutions adopted

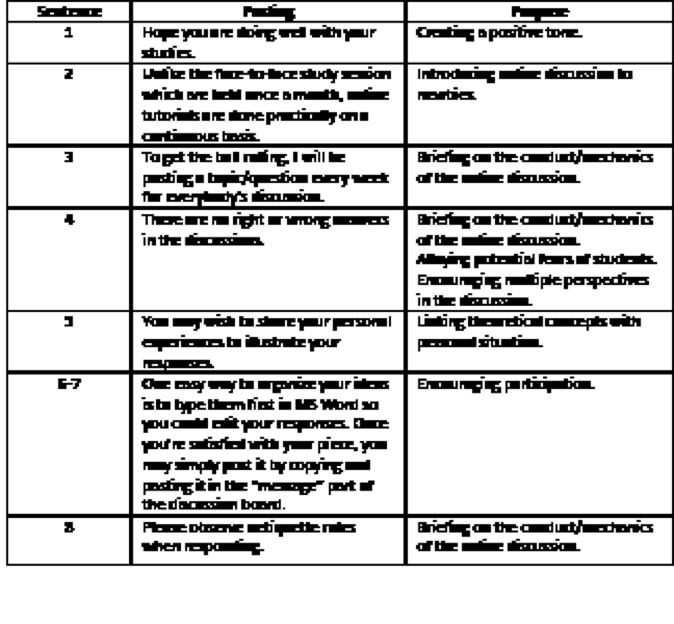

The online discussion forums were a new approach for us to conduct tutorials. At this point, participation in the online tutorials was still optional just as it was in the face-to-face study sessions. It was at this time when the word “online” began pervading our discussion at training and informal discussions in addition to words like “connectivity” and “interactivity.” But for the most part, “online” more or less referred to the online discussion forums. The other course requirements like tutor-marked assignments can now be submitted online but many of us still printed the downloaded assignments or asked our students to send in their requirements in print. And so, of all the challenges cited above, designing and facilitating online discussion required the greatest amount of thinking and planning on my part. To encourage the students to participate, I tried to come up with discussion questions that could elicit multiple answers and perspectives. On the topic of the nature of management, for instance, I asked them to answer the question “Is Management an art or a science?” To ease our foray into this asynchronous and technology-mediated mode of communication, I adopted some strategies like creating a positive tone, encouraging participation, and laying down the mechanics of the activity, as shown on Table 2.

I managed to sustain and direct the flow of the discussions by doing some follow-up postings, asking students to clarify their contributions, and encouraging other students to participate. In other instances, my time as an online tutor was spent on mediating discord in the discussions and setting ground rules to address conflict among the learners, as illustrated below:

Much as I want to encourage open and lively discussion at the Integrated Virtual Learning Environment (IVLE), there are certain standards of behavior that we need to uphold. Hence, I will be posting a set of ground rules at our course’s site to prevent such occurrence again. Attached herewith is a copy of those ground rules.

Table 2. Sample Faculty-in-Charge (FIC) introductory posting in an online forum (2002)

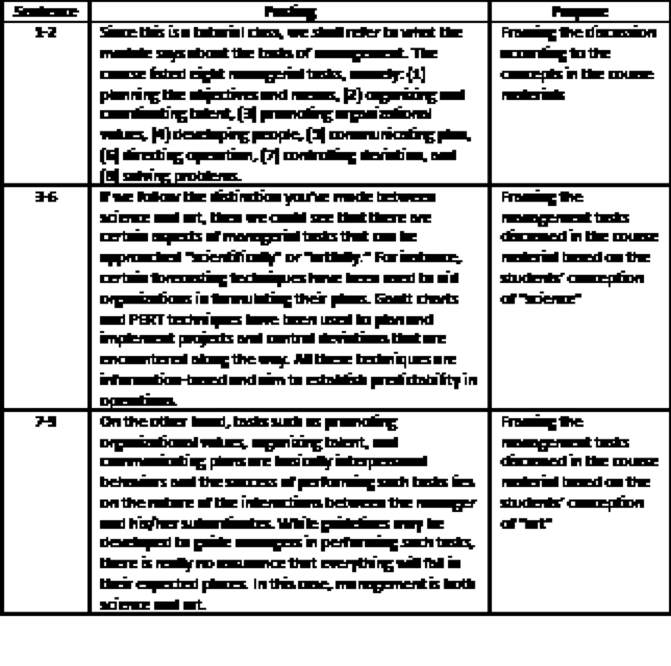

At the end, my primary contribution as the online tutor would be my synthesis of the discussion, which primarily consisted of summarizing the main points raised by the students and connecting the discussion with the theoretical concepts. In the following excerpt from my synthesis of the online discussion on the nature of management (Table 3), one can see how the ideas shared by the students were framed by the concepts provided in the prescribed course material, and vice versa.

Table 3. Sample FIC synthesis of an online discussion (2002)

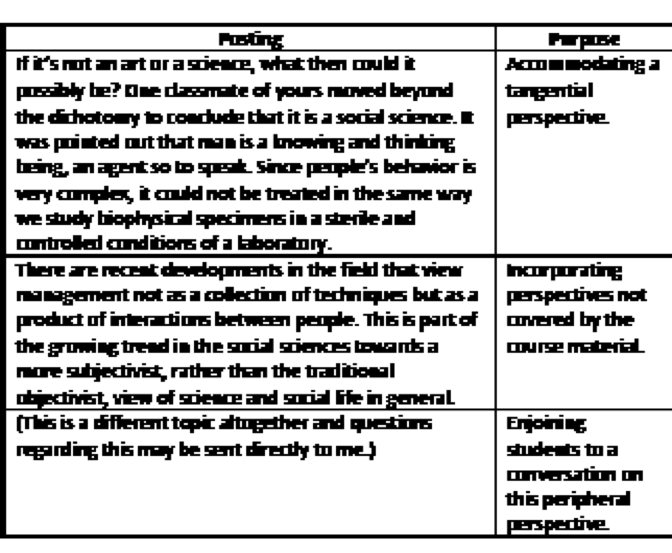

In spite of the guidelines and structure provided by the teacher, there were times when students would bring in ideas that may not fit with those of their classmates or the teacher. Depending on the relevance of the posting, my role as a teacher was to find ways of using the student’s contribution in bringing the discussion to a higher level (Table 4).

Table 4. Sample FIC’s treatment of a peripheral perspective in the online discussion (2002)

While I believed that the online discussions have opened up more space for learner-learner and learner-teacher interaction, I thought that the discussions were still strongly tied up with the print modules prescribed by the university. There is a growing realization that the materials were somewhat inadequate to create a fuller learning experience for the students. Referring to the third sentence in the posting shown in Table 2, there was an attempt on my part to open up the discussion to other perspectives by encouraging the students to cite other sources (and perspectives). In my posting in Table 4, I incorporated a tangential perspective in the discussion. In spite of these, the nature of the online tutorials at that time and the primacy of the perspectives presented in the course material meant that marginal perspectives remain as such.

This hankering for a wider range of perspectives came at a time when my views on research were also being challenged. It was during this time that I began collaborating on a research with a former colleague in the university where I used to work. (This university is also a constituent campus in the UP System.) Having been introduced to qualitative research in my master’s studies, I started to develop a huge interest in the methodology. I learned that this former colleague was doing her doctoral dissertation using qualitative research methodology. She shared her research experiences with me and this encouraged me to learn more about it.

In 2002, my colleague and I were invited to facilitate a roundtable discussion on the use of qualitative research in research and development (R&D) management studies. It was organized by the academic center where I was previously employed. The discussions turned out to be quite interesting, if not impassioned, so we decided to analyze the transcription of the discussions and publish our findings in a qualitative research journal. The study basically focused on our construction of qualitative research and our quantitative counterparts’ construction of the same. As we began to engage in more discussions about our study, I began to understand more how knowledge is basically a product of people’s interactions. After our article was published, we decided to work on a bigger study and this time problematize the centered and muted discourses in the field of R&D management, in particular R&D management research, R&D governance, and R&D management education.

Two other colleagues joined our team to tackle the other aspects of the study. I was assigned to examine the discourses in the teaching of R&D management by analyzing the texts in the course modules. It was not an easy task but it confirmed my growing realization: the course materials were quite effective in presenting the concepts and approaches in managing R&D organizations but there were aspects of R&D organizational life that seemed to have been marginalized in the modules—the socially constructed and artful nature of management and the role of power in managing organizations.

As I was contemplating on the nature of R&D management, the UPOU was also examining its status and future. The UP System was undertaking re-organization at that time and there were streamlining efforts in various parts of the University System. There were talks about realigning the functions and structure of UPOU. Efforts to expand curricular programs were put on hold. The emphasis was on improving the current offerings. There were also questions about the adequacy of the printed modular course materials in teaching graduate students. As have been argued, graduate students need to be exposed to a variety of reading materials and a wider range of perspectives than the ones being provided in the course manuals. While I appreciated the amount of effort put into the production of the reader-friendly manuals, a part of me seemed to agree with the contention.

Amidst this situation, I had also been working on securing a scholarship grant to be able to pursue my PhD studies abroad. In late 2003, I applied for a study leave from UPOU to pursue my doctoral studies in Australia.

I spent my succeeding three and a half years working on my PhD in organizations studies at Melbourne University. My doctoral thesis was a discursive study on the social construction of an Australian University’s organizational identities in the context of organizational change. As part of my study, I was exposed to the different schools of thought in organization and management.

In late 2007, I returned to UPOU. In spite of the downsizing of some offices, the university has succeeded in maintaining its mission and functions as an autonomous university offering distance education programs.

There were new faces and new systems. For one, we have moved on from a licensed Learning Management System (LMS) to an open source. I thought that the old LMS had a better environment but the new one has more features—online quiz, blogs, chats, and a host of other applications.

While the new LMS took some adjustments, the biggest change that struck me most was the university’s adoption of resource-based approach to teaching and learning. Instead of the usual printed course manuals, the university was now promoting the use of learning resources—including online articles, website, digital audio files, videos, and study guides—to promote higher thinking skills. The university has actually experimented on this approach even before I left for studies abroad. The main difference is that it has now become the standard approach to course material development for newly instituted courses. Faculty members and lecturers were still being trained in instructional design, but this time, the emphasis was on developing courses using online resources, including online articles, videos, and interactive sites and applications. More and more faculty members were also incorporating games, social media, blogs, and other web 2.0 technologies into their courses to promote interactivity, particularly in terms of collaborative learning.

In addition, FICs are expected to update the course materials of existing courses using the same approach. Whereas in the past, a course development team was organized to revise the old course manuals, FICs can now compile their own set of course materials as they see fit. The dictum “the module is the teacher” was no longer in fashion.

At first, I felt nostalgic about the familiarity of the old way of doing things. Having been away for almost four years, I had to familiarize myself with my familiar but equally strange environment. As expected, I was not alone in my uneasiness. There were other people in the university who were also concerned about this change. Some felt that in moving away from the course manuals, the university could lose the branding it had built with its printed modules.

It was quite ironic that I had these nostalgic feelings when I had actually conducted a research arguing the limitation of the printed course manuals. Having said this, any ambivalence I was having was replaced by what I believed to be the advantages of this approach. First, online resources are easier to source and organize which makes updating of course content faster as compared to the printed course manuals, which may be reader-friendly but were too costly to revise. Second, online resources come in various formats, which make them easier to disseminate and apply for different learning purposes. These were probably the same reasons why the university decided to go in this direction.

I was assigned to a course in R&D organizational structure, relations, and processes. Having been trained in organization studies for my PhD, I was excited to handle this course. Much as existing course manuals were quite effective in presenting the systems and functionalist perspectives on management, they need to be supplemented with other lenses for looking at organizations. I believed that this would not only enhance the students’ analytical skills but also make them better practitioners—managers who can think creatively and not be calcified by predictable ideas, respond to shifting and contesting organizational realities, and reflect on their relationship with and impact on their co-workers in their respective organizations.

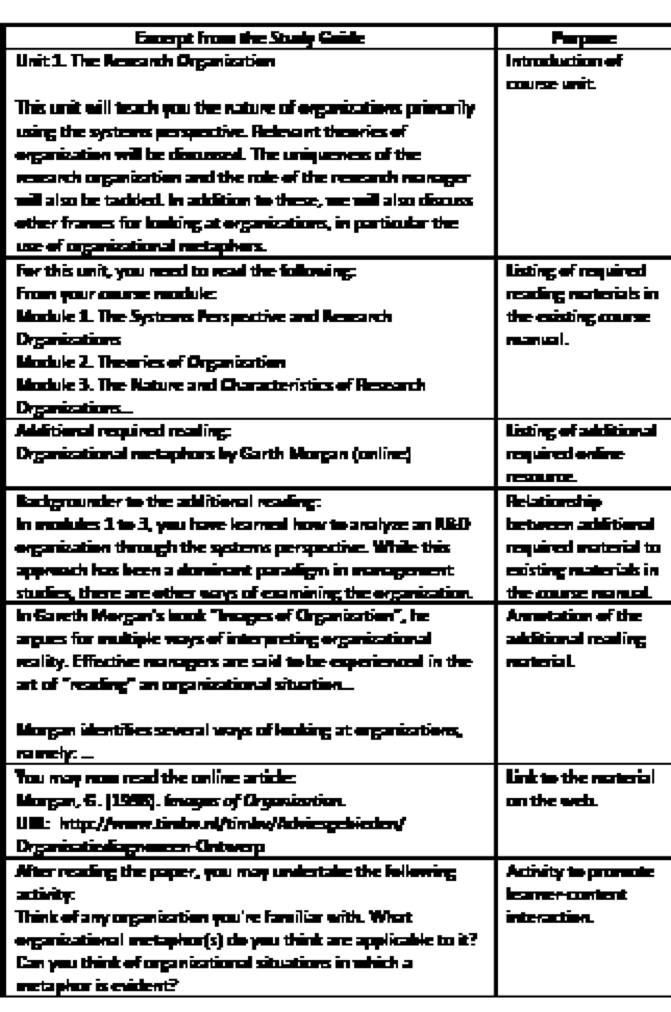

To expand the perspectives covered in the course material, I decided to include Gareth Morgan’s Organizational Metaphors as one of the required reading materials for the course unit on “The Research Organization.” While in graduate school, I bought a copy of Morgan’s book “Images of Organizations” which argued that organizations can be read as metaphors. I did not have to condense his ideas from the book, as there were quality online resources on the web tackling the same topic.

As a distance education teacher, I was aware of the unique context of my learners. I believed that while the course manuals had it limitations, the students benefit from the structure they provide. In other words, students do not get easily “lost” while reading the modular manuals. And so when I combined this new material with the existing ones (i.e., course manuals), I made sure that I explained the relationship between the two in the Study Guide that I prepared (Table 5). I believed that it was important for me to provide the students with enough scaffolding as they interact with this learning material.

Table 5. Supplementing the course manual with online resources

As part of the requirements in this module, I asked my students to participate in online discussion forum wherein they used any of Morgan’s metaphors to describe their own organizations. While a few students seldom used metaphors like “cultures” and “instruments of domination” to examine their organization, most still preferred to use the “machine” and “organism” metaphors which are associated with the systems and functionalist perspectives that were emphasized in the existing course manuals.

The second module of the same course covered the relationship between the R&D organization and its environment. In the existing course material, the “environment” is presented as a separate entity to which organizations must adapt in order to survive. Just like in the first module, I drew on Gareth Morgan to supplement the existing perspectives. According to Morgan, there are three schools of thought on the organizational environment—adaptationist, natural selection, and social constructionist. Just like in the previous example, most of my students related well with the adaptationist perspective, which is the commonly accepted view in management. In these cases, I will have to come in at the end of a discussion forum to clarify some of the misconceptions by expounding on the ideas presented in the learning material and relating them to the students’ postings, as shown below:

In the discussion, it was also argued that enactment is exhibited when managers/organizations come up with decisions based not on what is out there but on the former’s willful acts. There were some pretty good examples of companies that introduced new and innovative products (e.g., iPhone, news programs on primetime) that did not exist in the market but through the sheer creativity and tenacity of the organization’s leaders, new markets and industries were created, thus altering the environment forever. This is an example of people making sense of what the environment needs or wants and acting upon these interpretations. In this sense, the environment did not act upon these organizations. Instead, the organizations enacted it.

However, it has also been mentioned that enactment could be an “aggressive” form of adaptation. According to this perspective, we can see that the enactment process precedes adaptation. Adaptation is therefore a retrospective act—it comes after the fact. The managers’ actions can be explained not by the environment but their interpretations of it. From the enactment perspective, the environment is enacted or constructed as people make meanings about it (i.e., it does not precede or exist outside the meaning making).

From the enactment point of view, managers supposedly act in the now (whether or not they see this act as an adaptation or something else) and interpret this action later or in retrospect. It is only after the fact that those managerial actions are re-interpreted as “adaptation.”

Judging by the posting from a student as shown below, such discussion notes posted at the end of the forum help students gain a better understanding of the lesson:

Thank you Sir for the summary notes specifically for clarifying the difference between adaptation and enactment.

In some instances though, students are able to grasp the concepts as well as the interrelationships between these concepts. In this passage from an online discussion, notice how a student (who, by the way, chose to describe his organization as a “machine”) saw the relationship between the metaphorical lenses he chose and the way he perceives an organization should relate to the environment:

Student A:

Hi classmates. I realized that the concepts of organizational metaphor and the three schools of thought that we just read are very much related and complement each other. The organizational metaphor that one uses to compare his/her organization has a big influence on what school of thought he/she will use to analyze it. For example, I compare the milling plant of our company to a machine, whose parts can be replaceable to satisfy needs. Because of this, I think that our plant is best seen as an adaptive organization; changing its metal flow sheets and reorganizing people depending on the buyers’ demands. Also, one may believe in the enactment theory if he sees his organization as a brain!

Student B:

Hi [Student A]! I love your idea. This is what I am trying to drive at in my post. Keep up your good work…

It is moments like this when a teacher remembers why he/she got into teaching in the first place.

The use of online materials available on the web extends beyond the course materials. I have also used it as a springboard for my students to do written assignments. In the module on the culture of organizations, for example, I required my students to describe and analyze the culture of their organization using The Cultural Web, which I found on the web (Mind Tools, n.d.). I thought that the framework could help the students surface the values that are embodied in their stories, rituals and routines, symbols, organizational structure, control systems, and power structures.

Despite having a relatively specific set of guidelines for this assignment, I have observed that there were some students who still cannot seem to identify the “values” behind the practices and artifacts in their organizations. In the succeeding semester, I made my guidelines more structured by providing them a sample matrix to help them delineate those “values.”

Since I returned from my PhD studies several years ago, I experimented with some teaching and learning strategies, including collaborative learning, online assessment, and peer assessment. I was also given an opportunity to handle another graduate course where I personally assembled all the online course materials and designed all the learning activities.

In 2010, the university organized a series of colloquia on the relationship between distance education and the disciplines that we teach. I was one of the faculty members who were invited to give a talk. In one of those discussions, somebody asked whether there were fundamental differences between online teaching at UPOU and face-to-face teaching. Some believe that there was not much difference while others argued that the asynchronous and textual nature of the interaction makes the facilitation in online classes more difficult and laborious. I am aware of these challenges and there were times that I have struggled to tackle these challenges.

I can understand why people see the gap between online teaching at UPOU and residential teaching closing more than ever. As a former teacher in a residential university, I appreciate the leeway given to teachers in the way they handle their classes. In recent years, UPOU teachers have been given greater freedom to select and design their own learning materials given the limits of the approved course description and learning goals and guided by the instructional design training they have received. But as a teacher in an open university, I also recognize the importance of providing structure to the learning experience. While I am given a greater role in deciding what to impart to learners, I am also aware that this content is still delivered through technical media. As a teacher, it is my role to guide my students engage with this content and be clear about the requirements they are expected to meet.

Looking back, I can say that my role as an ODeL teacher can be summarized as follows: facilitating discourse, encouraging participation, developing content, designing learning activities, assessing student learning, and providing student support. These roles are not much different from those of a teacher in a conventional classroom. While the time and space difference between and among the teachers in distance learning adds another layer of complexity to the teaching and learning context, ODeL and face-to-face teachers share the same vision—to see their students achieve their full potential as learners and professionals in their chosen fields.

I am not sure how teaching and learning at UPOU will evolve in the future. The possibilities appear to be endless. New technologies will be developed and bring ODeL to a new level or direction. In the end, the community of scholars and stakeholders that comprise UPOU would continue to construct and re-construct their narratives and enact their teaching and learning realities in this constantly adaptive worldview that is ODeL.

Morgan, G. (1986). Images of organizations. Beverly Hills, California: Sage Publications.

Stanley, L. (1993). On Auto/Biographies in Sociology. Sociology, 27, 1, 41-52.

Suggested citation:

Garcia, P. G. (2014). Becoming an ODeL Teacher at UP Open University: An Auto-Narrative. In G. J. Alfonso, & P. G. Garcia (Eds.), Open and Distance eLearning: Shaping the Future of Teaching and Learning (pp. 51-68). Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines: UP Open University and Philippine Society for Distance Learning.