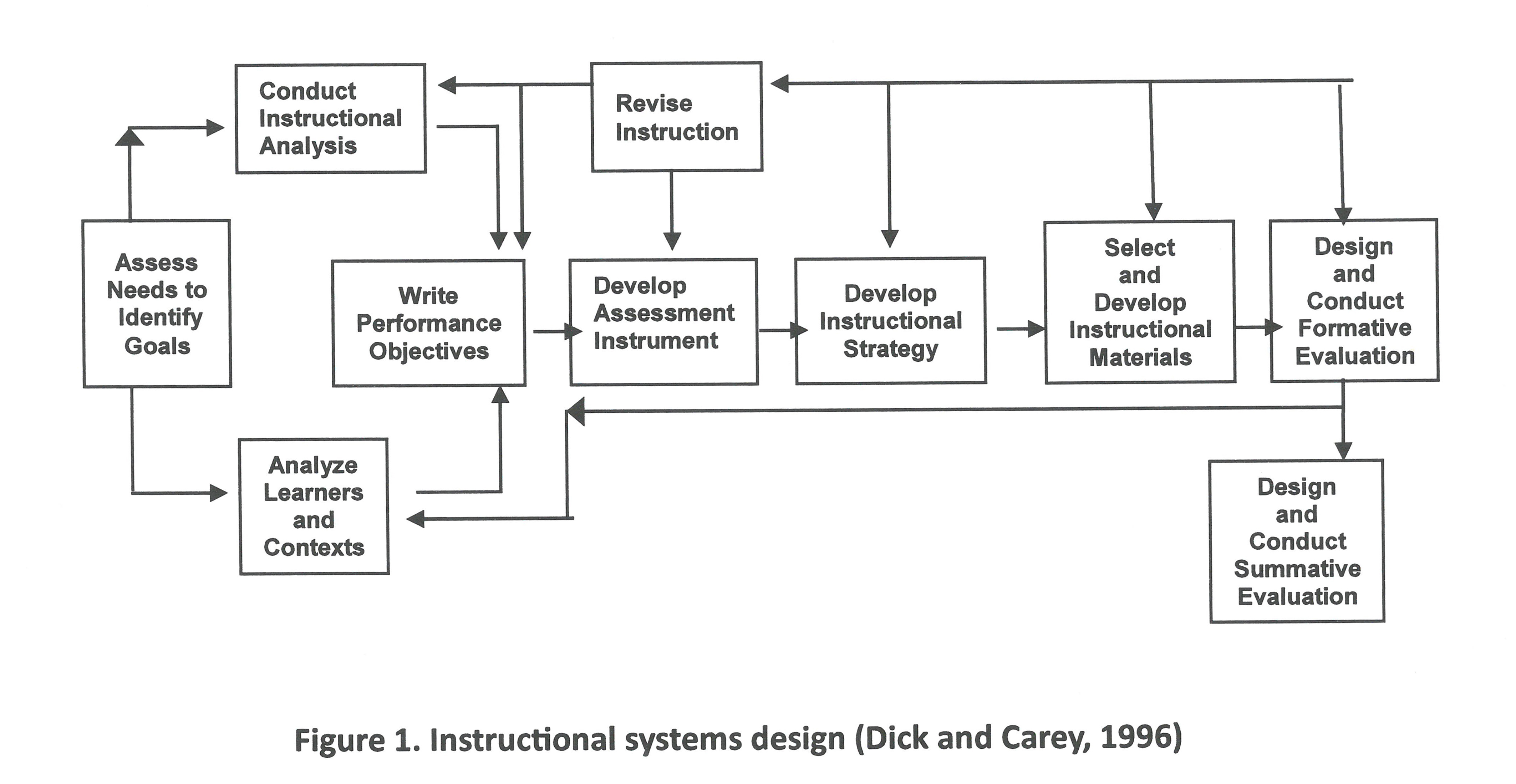

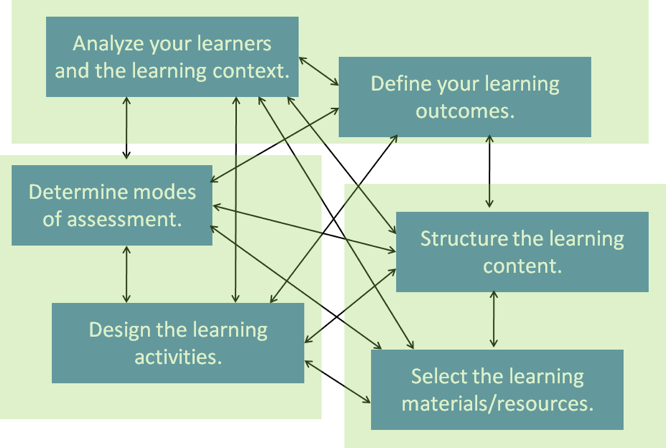

Course design in distance education (DE) has been evolving in the last 15 years as a result of the increasing availability of new information and communication technologies. Traditional DE consisted of print-based materials developed by course teams consisting of subject matter experts, instructional designers, editors, multimedia designers and editors, and library support staff, among others (Calder, 2005; Haughey, 2010; Naidu, 2007). The course teams would take one to two years to develop materials using the systems approach to instructional design (see Figure 1). Because of the number of experts, length of time, and other resources involved, this approach to DE course design and development was “costly” (Naidu, 2007). However, the high costs could be justified by the production of high-quality self-instructional materials that could be “presented to large numbers of students with the support of tutors who are often part-time, contract staff” (Calder, 2005, p. 232) over several course offerings.

Figure 1. Instructional systems design (Dick and Carey, 1996)

The advent of computer and web technologies changed the mode of DE from print-and-post to computer-mediated and online. The change was not only in course delivery but also in course design and development, with the emergence of the resource-based approach as an alternative to the course team approach. In online resource- based courses, learners work with a mix of tailor-made learning resources such as study and activity guides, and existing materials like textbooks, websites, and rich media resources, instead of pre- packaged course materials (Jara & Fitri, 2007; Mason, 1998). Mason calls this the wraparound or 50/50 model in her typology of online DE courses, and she differentiates it from the traditional content + support model of DE and the integrated model. The content + support model is characterized by the separation of the course content, which is pre-packaged and “relatively unchanging,” and tutorial support, which is usually provided by tutors who are not the course authors. In the integrated model, which Jara and Fitri (2007) call the discussion-based model, the course contents are “fluid and dynamic” because they are created during synchronous and asynchronous online collaborative activities. Also, in discussion- based courses the course author and the tutor are the same person. In the wraparound or resource-based model, tutors or teachers have a more extensive role in course design “because less of the course is pre-determined and more is created each time the course is delivered, through the discussions and activities” (Mason, 1998, pp. 6-7).

The involvement in course design of teachers-in-charge (Naidu, 2007) or faculty tasked with course delivery is an important difference between the industrialized print-based model of DE course development and the postmodern, post-industrial, and digital model of DE course development. In the former, course design was undertaken through division of labor among specialists working as a team, and it took place during course development, before course delivery. In the latter, course design is undertaken by “a reduced version… of the course team approach” where faculty members both design and deliver the courses asynchronously online (Power, 2007, p. 65). Course design in the latter also tends to be “ad hoc” rather than “planned” or “centralized” (Davis, 2001, p. 10) and the design process is much more fluid, taking place not just before but throughout course delivery. It is in this context that rapid instructional design is best understood as a course development method in DE.

Rapid instructional design is described by Thiagi (1999, 2008) as “faster” and “cheaper” instructional design that results in “better” learning because it focuses on absolutely essential skills and concepts and it fosters active learning. At the UP Open University (UPOU), rapid instruction design has been adopted as a means of

-

- * developing web-supported DE courses that are learner/ing- centered, knowledge-centered, assessment-centered and community-centered (Anderson, 2008a);

- * engaging Faculty-in-Charge in the design process and helping them to adopt innovative pedagogies; and

- * regular updating of course materials at minimal cost, thereby enabling the ODeL institution to maintain quality in a cost- effective

The open and distance e-learning (ODeL) model being implemented at UPOU is one where students engage in guided independent study of resource-based course packages and online tutorials conducted through a Modular Object Oriented Dyanmics Learning Environment (Moodle) – based virtual learning environment (VLE). This open source VLE allows for the creation of courses featuring two types of content: resources and activities (Blin & Munro, 2008). Resources are usually digital materials like webpages, PowerPoint presentations, and files in portable document format that are created outside of the VLE and uploaded or linked to the course site on Moodle. Activities include discussion forums, chat rooms, and online quizzes that are generally created directly on the Moodle system to enable interaction and dialogue among learners

Training workshops on how to use Moodle are conducted regularly for all of UPOU’s Faculty-in-Charge (FIC). In addition, FICs may request individualized tutorials from techsupport staff. However, although UPOU shifted to the use of Moodle in 2007 and online tutorials were adopted at UPOU in 2001, we noted the persistence of the following issues in faculty use of the VLE:

-

- *Some course sites or virtual classrooms are not prepared for student use before the semester begins. Thus, upon entry, students find these course sites bare, without basic resources such as a course guide to give students an overview of the course, an introductory message or instructions from the FIC, and an introductory forum where students might at least introduce themselves.

- * Many of the functionalities of the online learning platform are not sufficiently utilized to engage learners, to facilitate and enhance learning, and to foster dialogue and collaboration. For example, few FICs have tried out the online quiz tool, the use of chats, and the use of the blog and wiki

- * The most used functionality or feature of the learning management system (LMS) is the discussion forum. However, there is minimal and sometimes no teacher moderation of or participation in these forums beyond setting the forum

- * In many cases, faculty do not give timely feedback on student assignments.

Analysis of these issues led us to conclude that a basic workshop on how to use Moodle is inadequate for faculty to learn how to design online courses well. To be able to teach effectively with technology, faculty members need to develop not only the requisite technology skills (i.e., skills in the use of particular hardware and software) but also a deep understanding of how using particular technologies might change the dynamics of teaching and learning (Arinto, 2008). As Mishra and Koehler (2006, p. 1030) put it, “The addition of a new technology is not the same as adding another module to a course. It often raises fundamental questions about content and pedagogy that can overwhelm even experienced instructors.” Indeed, using a VLE like Moodle, especially in a DE context (i.e., where teachers and students do not meet face-to-face in a physical classroom), requires teachers to think carefully about how they would chunk and sequence course content, what types of learning resources to make available, and what mix of individual and collaborative activities to provide in order to foster deep and active learning. In short, FICs using Moodle need to do instructional design.

Following this analysis, we designed a workshop on rapid instructional design for FICs that is based on Anderson’s (2008b) conceptualization of the roles of the online teacher, and a framework for designing online courses derived from Anderson’s (2008a) attributes of effective online DE, Beetham’s (2007) approach to e-learning activity design, and Thiagi’s (1999 and 2008) rapid instructional design methodology.

According to Anderson (2008b), the online teacher’s roles include designing and organizing the learning context, supporting learning and facilitating discourse, assessing learning, and providing direct instruction. The rapid instructional design workshop highlights the online teacher’s role as course designer, which according to Anderson (2008b) involves developing, updating, and/or customizing course content; and designing learning activities that maintain a balance between independent study and community building, facilitate deep exploration of content, and provide for effective assessment of learning. Anderson’s (2008a) model of online learning shows high levels of interaction among the learner, the content, and the teacher made possible by effective use of web-based learning resources and communication tools. Thus, for Anderson (2008a) effective online DE is learner- or learning- centered, knowledge-centered, assessment-centered, and community-centered. This online learning model is compatible with Beetham’s (2007) principles of effective e-learning design, namely: (1) design for learning outcomes; (2) design for learners; (3) design with digital tools and resources; and (4) design for interaction with others. These principles can be applied at any of four levels of design—course design, session planning, activity design, and learning object design (Beetham, 2007).

Anderson’s description of what online teachers do when they engage in design work matches Thiagi’s rapid instructional design methodology which aims to ensure that the three components of effective learning are present:

-

-

- Content related to the instructional objectives;

- Activities that require learners to process the content and to provide a response; and

- Feedback to learners to provide reinforcement for desirable responses and remediation for undesirable responses.

-

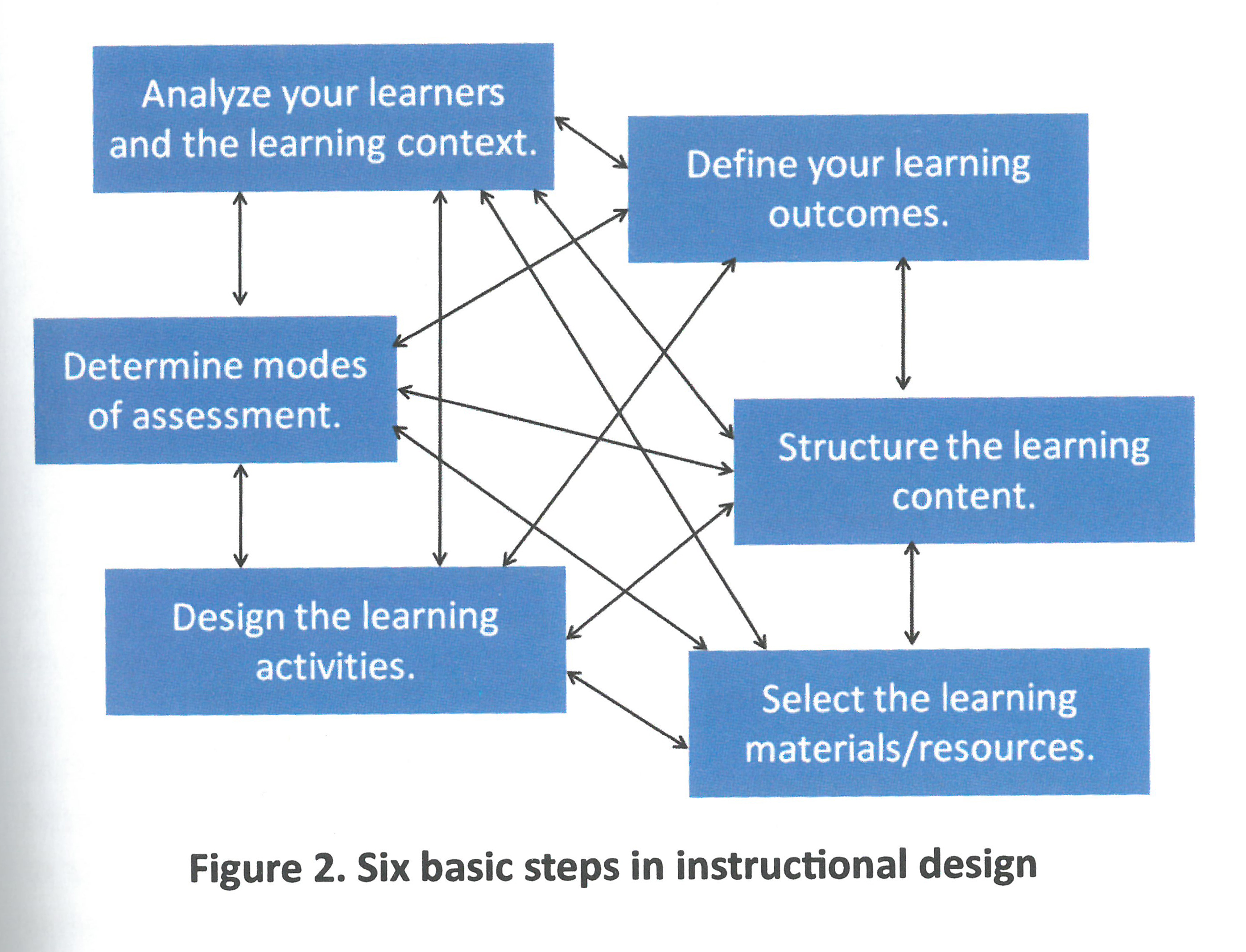

Thiagi’s methodology is called rapid instructional design because it involves significantly fewer steps than the steps in traditional instructional design shown in Figure 1. Traditional instructional design is a lengthy process but FICs usually have little time to prepare for course delivery (although course assignments are given at least one semester ahead, FICs often have to juggle teaching as well as research and administrative loads within a semester). Thus, it is necessary to adopt a more streamlined approach to traditional systems design (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Six basic steps in instructional design

We can then map Thiagi’s method of rapid instructional design on to the streamlined approach to reduce the six steps to three (Figure 3).

We propose further that since learner demographics are already available at the program level and since the course objectives are already set and not normally changed during course delivery, it is possible for FICs to focus on just two steps. These two steps are: (1) selecting existing content and customizing it; and (2) designing learning activities around this content.

Figure 3. Grouping steps in instructional design

The rapid instructional design methodology described in the preceding section is both content-driven and activity-focused. The focus on content is significant because, as Anderson (2008a) reminds us, “[e]ffective learning does not happen in a content vacuum.” This means that people develop thinking and other skills within the context of particular knowledge domains or disciplines. Thus, for example, people learn how to write in an academic way by being exposed to examples of academic writing, rather than to written resources in general. Our rapid instructional design methodology in a web-supported environment allows DE teachers to prepare a menu of content-rich resources in various formats and diverse contexts that learners can explore in order for them “to grow their knowledge and find their own way around the knowledge of the discipline” (Anderson, 2008a, p. 49).

The activity-focused aspect of rapid instructional design, on the other hand, is important in helping faculty to design online learning environments that are “rich in resources, tools, and learning materials, and that offer ample opportunities for social interaction and collaboration… [and] extensive opportunities for practice with the different categories of knowledge and skills” (de Corte, 1996, 124, in Calder, 2005, p. 232). Such learning environments are underpinned by a social constructivist perspective on learning, or the view that learning is a process of constructing knowledge through social interaction and application in authentic contexts (Anderson & Dron, 2011). In social constructivist learning, students are fully engaged and they are active participants in a learning community. Especially in DE contexts, this represents an ideal of sorts, indicating successful negotiation of the transactional distance (Moore, 1997) between learner and teacher and among learners that is inherent to the teaching-learning transaction and exacerbated by physical distance.

The rapid instructional design methodology described in this paper also has the added advantage of increasing the level of engagement of the ODeL teachers themselves. One of the negative aspects of the traditional content + support model of DE was the feeling of alienation it engendered, especially among faculty in-charge of course delivery. This alienation came from a loss of autonomy and control over the teaching process which was cut into various phases and “distributed” (Guri-Rosenblit, 2009) among the senior academics who planned the courses and developed the course materials, the junior faculty who planned assessment activities and served as course coordinators during the course offering, and mostly part-time lecturers who served as tutors and counsellors (Arinto, 2007). In contrast, in online DE the boundaries between course development and course delivery are blurred and there are opportunities for increased faculty control of courses (Abrioux, 2001). Mason (1998) and Jara and Fitri (2007) refer to the increased role of tutors in the design of online resource-based courses. Tait (2010) refers to the expansion of the mediating role of online teachers to include helping learners “to make sense of the wealth of resources which they can, with guidance, find themselves” (pp. x-xi).

A fourth advantage posed by our rapid instructional design methodology is that it is a relatively inexpensive way of “updat [ing] the study materials on an ongoing basis” (Guri-Rosenblit, 2009, p. 106). In the industrial model of DE course development, the revision and redevelopment of course materials is not easily managed as it requires the (re)constitution of course teams, the (re)organization of faculty workloads, and the (re)allocation of time and other resources. In contrast, the rapid instructional design methodology presented here is parsimonious: it involves only the course faculty and it can be implemented quickly.

Rapid instructional design poses a number of advantages, as discussed in the previous section. However, certain conditions need to be met for these advantages to be realized. First, faculty need to undergo training in design for learning. The training should be a holistic program in teaching effectiveness in ODeL. Thus, it should highlight the principles of effective learning discussed previously, and not be narrowly focused on design as a technological skill. Second, faculty should be provided tools and resources to guide them in their design work. Examples of these are frameworks, models, and templates, as well as standards, guidelines, and procedures that the faculty can use as reference points for their work.

For the institution as a whole, these quality standards and systems would be an important means for gauging success in ODeL. This is the third condition for rapid instructional design to improve the quality of online teaching and learning. More specifically, institutions should put in place a system for regular and timely review of both the process and outcomes of course design. This system should aim to implement the appropriate standards for the design of online DE courses, such as accessibility for all students, appropriate types and levels of interactivity, and relevant and up-to-date content, as well as appropriate use of proprietarial and open educational resources. The standards to be implemented are in a sense the principles of effective instructional design which, following the process of instructional design, should also underpin the training and support programme for faculty as course designers.

Abrioux, D. (2001). Guest Editorial. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 1, 2. Retrieved from http://www. irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/issue/view/10

Anderson, T. (2008a). Chapter 2 – Towards a theory of online learning. In T. Anderson (Ed.). The theory and practice of online learning (pp. 45-74). Athabasca University Press.

Anderson, T. (2008b). Chapter 14 – Teaching in an online learning context. In T. Anderson (Ed.). The theory and practice of online learning (pp. 343-365). Athabasca University Press.

Anderson, T. & Dron, J. (2011). Three generations of distance education pedagogy. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12, 3, 80-97. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl. org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/890/1826

Arinto, P. (2008). What and How Teachers Know When Teaching with Technology: The Perspectives of Four Filipino Teacher Educators. Unpublished EdD Institution-focused Study Report, Institute of Education, University of London.

Arinto, P. (2007). Going the Distance: Towards a New Professionalism for Full-Time Distance Education Faculty at the University of the Philippines. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 8, 3. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/ irrodl/article/view/409/941

Beetham, H. (2007). An approach to learning activity design. In H. Beetham & R. Sharpe (Eds.). Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age. London and New York: Routledge.

Blin, F. & Munro, M. (2008). Why hasn’t technology disrupted academics’ teaching practices? Understanding resistance to change through the lens of activity theory. Computers & Education, 50, 475-490.

Burge, E. J. & Polec, J. (2008). Transforming learning and teaching in practice: Where change and consistency interact. In T. Evans; M. Haughey; & D. Murphy (Eds.). International Handbook of Distance Education. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.

Calvert, J. (2005). Distance education at the crossroads. Distance Education, 26, 2, 227-238.

Davis, A. (2001). Athabasca University: Conversion from traditional distance education to online courses, programs and services. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 1, 2. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/issue/ view/10

Guri-Rosenblit, S. (2009). Distance education in the digital age: Common misconceptions and challenging tasks. Journal of Distance Education/Revue de L’education a Distance, 23, 2, 105-122.

Haughey, M. (2010). Teaching and learning in distance education before the digital age. In M. F. Cleveland-Innes & D. R. Garrison (Eds.). An introduction to distance education. Understanding teaching and Learning in a new era. New York and London: Routledge.

Jara, M. & Fitri, M. (2007). Pedagogical templates for e-Learning. London: Institute of Education. Retrieved from http://www. wlecentre.ac.uk/cms/files/occasionalpapers/wle_op2.pdf

Mason, R. (1998). Models of online courses. ALN Magazine, 2, 2. Retrieved from http://www.old.sloanconsortium.org/publications/ magazine/v2n2/mason.asp

Mishra, P. & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A new framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108, 6, 1017-1054.

Moore, M. (1997). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.). Theoretical principles of distance education (pp. 22-38). Routledge. Retrieved 12 October 2009, from http://www.aged.tamu. edu/research/readings/Distance/1997MooreTransDistance.pdf

Naidu, S. (2007). Instructional designs for optimal learning. In M. G. Moore (Ed.). (2007). Handbook of distance education. New York and London: Routledge.

Power, M. (2007). From distance education to e-learning: A multiple case study of instructional design problems. E-Learning, 4, 1, 64- 78.

Power, M. & Gould-Morven, A. (2011). Head of gold, feet of clay: The online learning paradox. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12, 2, 19-38. Retrieved from http:// www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/916/1785

Tait, A. (2010). Foreword. In M. F. Cleveland-Innes & D. R. Garrison (Eds.). An introduction to distance education. Understanding teaching and learning in a new era. New York and London: Routledge.

Thiagi. (2008, May). Integrate content and activity. Thiagi Gameletter. Retrieved from http://www.thiagi.com/pfp/IE4H/ may2008.html#99WordsTip

Thiagi. (2008, February). Rapid instructional design: Learning activities that incorporate different content sources. Thiagi Gameletter. Retrieved from http://www.thiagi.com/pfp/IE4H/ february2008.html#RapidInstructionalDesign

Thiagi. (1999). Rapid instructional design. Retrieved from http:// www.thiagi.com/article-rid.html

Suggested citation:

Arinto, P. B. (2014). Rapid Instructional Design for ODeL Course Development. In G. J. Alfonso, & P. G. Garcia (Eds.), Open and Distance eLearning: Shaping the Future of Teaching and Learning (pp. 69-82). Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines: UP Open University and Philippine Society for Distance Learning.