Quality has been a long-standing issue in open and distance education. This chapter ventures to identify some pressing issues faced by open and distance learning (ODL) institutions in efforts to achieve quality through an appropriate quality assurance (QA) approach. It traces the evolution of the concept of quality and QA in higher education, how it has been applied in open and distance education and identifies current quality and equity issues such as widening access, digital inclusion, contextualization, and partnerships taking place in the context of a technology-enhanced education system. The chapter sets the stage for the succeeding chapters of the book which deal with initiatives of an open and distance e-learning (ODeL) institution driven by the requirements and demands of Industrial Revolution 4.0, Web 4.0, and Education 4.0.

While the concepts of quality and quality assurance (QA) originated from the manufacturing sector, its application has become imperative in the field of education. Recent literature shows various scholarly reviews (Allais, 2009;Harvey, 2005; Kanwar, 2013; Mishra, 2007; Vidovich, 2001) that describe the evolution of the concept of quality and related terms such as total quality management, accreditation and certification, and QA and how the education sector has adapted the concept, approach, and measurement of quality and QA.

In higher education, quality as a concept has been considered to be multi-dimensional and ever-changing (Vidovich, 2001), often encompassing all academic functions and services such as “teaching and academic programmes, research and scholarship, staffing, students, infrastructure and the academic environment” (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 1998, p. 1). QA, on the other hand, has been defined as the means to achieving quality using quality standards in assessing and ensuring the potential of educational institutions to effectively perform and deliver these functions and services (Friend-Pereira et al., 2002) and is often conducted either through internal self-evaluation or by an external review body (UNESCO, 1998). In the past, QA was imposed through a set of fixed criteria that was applied to the entire educational system. However, as the concept of learning itself evolved and institutions began to realize that quality for higher education is a continuous process of adjustments, reflections, and reforms, the approach to QA slowly shifted towards using a set of more flexible criteria that recognizes the individual experiences of institutions (Reisberg, 2010). As higher education institutions (HEIs) became diverse in terms of their systems, traditions, and identities, scholars argue that the set of criteria used for QA should be more “constructively ambiguous” and should allow for different interpretations of quality (Sobrinho, 2008, as cited in Reisberg, 2010, p. 19).

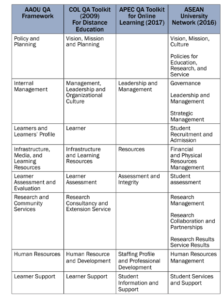

In line with the development of the concept of quality, models, and frameworks to ensure quality education in HEIs and evaluation of these models and frameworks were conducted. Some of these frameworks include the Asian Association of Open Universities (AAOU) framework, Commonwealth of Learning (COL) QA toolkit, and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) University Network (AUN) QA model. In 2015, Ossianilson et al. provided a global overview of the existing quality models in online and open education.

With the introduction of distance education (DE), new conditions and structures have emerged in higher education, necessitating alternative ways of conceptualizing and measuring quality. For instance, faculty roles, course development and delivery, student support, and use of learning resources in DE could be far different from traditional classroom-based education. In these digital times, DE, which includes online or e-learning, largely relies on an information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure to backstop academic and non-academic operations of the institution. Needless to say, new and emerging conditions presented by DE, as a modality of teaching and learning, challenge the validity of existing QA systems in higher education.

While there are those who argue that DE is already being considered as a long-established form of higher education and thus can be treated in the same way as traditional education, there are also those who assert that, with the uniqueness in its mode of educational delivery, DE might find existing QA mechanisms insufficient (Stella & Gnanam, 2004). Moreover, under an open and distance learning (ODL) set up, where the inclusion of the open philosophy in all aspects of teaching and learning is emphasized (e.g., open admissions, open curriculum, open educational resources), quality and QA concepts continue to be challenged which has triggered changes in the

education sector as made apparent in the so-called Education 4.0 scenario.

In this chapter, we venture to identify some pressing issues faced by ODL institutions in their efforts to achieve quality through an appropriate QA approach, setting the stage for the succeeding chapters of the book which deal with initiatives of an open and distance e-learning (ODeL) institution. We begin with the evolution of the concept of quality and QA in higher education and how it has been applied in open and distance education. Relevant quality issues in a technology-enhanced/mediated education system driven by the requirements of Industrial Revolution 4.0, Web 4.0, and Education 4.0 are identified.

Early literature noted that the quality movement started during the pre-1900s with “quality as an integral element of craftsmanship” evolving to a “total quality management system” during the 1990s (Sallis, 1996, as cited in Mishra, 2007). Some of the influential thinkers of quality included Edward Deming, Joseph Juran, and Philip Crosby, among others.

Deming(1982), considered as the father of the quality movement, published a book containing the “theory of quality management” in which he stressed on “prevention rather than cure as the key to quality” (p. 18). On the other hand, Juran (1989) defined quality as “fitness for purpose” while Crosby (1984) defined quality as “conformance to customer requirements” (Mishra, 2007, pp. 18–19).

Quality first started as a concept in the industry and the field of management during the 1920s (Mishra, 2007). Whereas, QA traces its origin in the industry during the second half of the twentieth century in which large-scale manufacturing organizations monitor the quality of their product to prevent having defective ones through the establishment of QA of systems and processes in all steps of the production, known as “quality control” mechanisms (Allais, 2009).

Quality is known to be a subjective, elusive, and complex term. Schindler et al. (2015) expounded on three challenges in defining quality as a concept. Primarily, quality is an elusive concept that connotes different meanings for different stakeholders. Quality is also a multidimensional concept which entails defining it as one-dimensional will result in a “lack meaning and specificity or are too general to be operationalized” (p. 4).

Lastly, quality is a “dynamic” concept that must be viewed in a larger context in the educational, economic, political, and social landscape. A definition of quality is a requirement in constructing definitions of QA as one should understand quality before acting on assuring it (Schindler et al., 2015).

By the 1970s, as influenced by business models, QA, as a concept, was disseminated in different sectors, including the government which is closely associated with education. This was prompted by the shift in the focus of quality management, a concept associated with QA, to the systems and processes from merely ensuring quality at the product level (Allais, 2009). In the Australian context, Vidovich (2001) is credited with having studied the discourse on the history of QA in relation to educational policies. There have been multiple and contradictory discourses on quality but the concept of quality as “excellent standards” prevailed. Moreover, internal stakeholders were given greater emphasis than external stakeholders. Prevalence of qualitative peer judgements is also evident.

By the mid-1990s, the approach to quality started in HEIs. In this time period, the concept of “QA” prevailed over “excellent standards”. Quality was further recognized by institutions as it has policy implications. Qualitative and quantitative data were also supplied by institutions, although the latter was dominant since quantitative performance indicators were emphasized. It can also be noted that external stakeholders were driving the quality agenda in this period (Vidovich, 2001). Towards the end of the decade, Vidovich (2001) recorded that QA in higher education was more focused on outcomes and external stakeholders. Institutions were also expected to have “improvements” as quality assessments have shifted from “reviews” to “audits.” In terms of discussions on its policy implications, institutions were in a dilemma between institutional autonomy and the need for accountability. The prospective balance of qualitative and quantitative assessments was scantily discussed. Differences between DE and traditional classroom were also discussed by Stella and Gnanam (2004) in their study, where they cited a number of existing QA policies and practices in higher education from various sources and argued that QA in DE has to be approached differently. The study of Thurab-Nkhosi and Stewart (2009) analyzed the QA processes of an evolving and dual mode university, the University of the West Indies Distance Education Centre (UWIDEC), in relation to conventional approaches to QA in higher education. For quality, defined as “fit for purpose” (p. 264), to be attained at the course level, the organization needs to ensure: institutional support, effective course development, earner-centered interactive delivery, support for students, support for faculty and a system of evaluation.

Kanwar (2013), in a brief overview of DE’s history, cited that when the first known distance teaching and open universities, the University of South Africa in 1946 and The Open University in the United Kingdom (UK) in 1969, respectively, “there was no discussion of QA as it is understood now” (p.xvii). Citing Mills (2006), Kanwar mentioned that “standards” or “objective measurable outcomes” in the form of faculty, infrastructure and facilities, entry requirements, prescribed curriculum, attendance, and evaluation procedures were used to assess an institution’s performance during the period of 1960s to 1970s. Soon after, as the concept of DE further developed, these standards got refocused to course preparation, quality of materials, feedback, and interactivity. With the emergence of information communication technologies (ICTs) in the 1990s, these quality standards were once again expanded to include personalization and interactivity (Kanwar, 2013).

Uses of e-portfolio, blogs, or wiki are examples of integrative assessment where the focus is on quality of analysis of approaches to learning (rather than learning itself). Asking students to reflect on what they have learned also adds to their understanding of the lesson as well as its application to their future learning (See Figure 4).

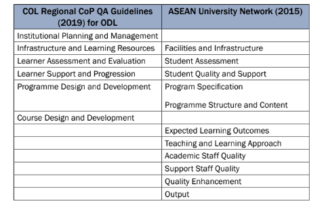

Jung (2007) acknowledged that based on a 2005 survey, a culture of quality was observed to be emerging or has been fully integrated in ODL institutions, with some of them having a central QA unit. There was also an apparent desire not only for internal but also for external accreditation. Belawati and Zuhairi (2007) described Universitas Terbuka’s innovative QA system, which adhered to the concept of quality as a continuous improvement rather than an end state. It contextualized the AAOU QA Framework for a mega university such as the Universitas Terbuka. In 2010, the University of the Philippines Open University (UPOU) participated in the Round 1 Delphi Study in improving the draft AAOU QA Framework (AAOU 2010 Annual Report, 2011). Among the notable QA frameworks and models for ODL institutions and programs are the AAOU QA framework, the Commonwealth of Learning (COL) Regional Community of Practice (CoP) QA Guidelines in ODL, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) QA of Online Learning Toolkit. The COL has its QA toolkit at the institutional level that is dedicated to DE. In the ASEAN Region, the ASEAN University Network’s (AUN) QA framework is the most widely used QA framework of HEIs; however, it is not specifically designed for ODL institutions. At the institutional level, the COL QA Toolkit for DE and AAOU QA Framework exhibits identical QA standards/criteria. In comparison to the two, the APEC QA toolkit adds emphasis on review and improvement, student experience, and learning outcomes. By contrast, the AUN-QA covers a more comprehensive list of QA standards/criteria (Table 1).

Table 1

Comparison of QA frameworks and models at the institutional level

Both the APEC and AAOU have no QA framework/model at the programme

level. The AUN-QA Framework consists more standards/criteria than the

COL Regional CoP QA guideline. Nonetheless, the two frameworks/models

are similar in four aspects—facilities and infrastructure, student support,

program design and structure, and assessment (Table 2).

Table 2

Comparison of QA frameworks and models at the program level

By the start of the millenium, approaches in dealing with the QA of open and

distance education developed, especially with the emergence of electronic

learning or e-learning. Kidney et al. (2007) identified eight (8) strategies

in a QA approach in e-learning courses to include instructional design,

web development, editing, usability and accessibility, maintainability,

copyright, infrastructure impact, and content and rigor. Frydenberg (2002)

presented nine (9) sets of standards that must be explored in the case

of quality standards for e-learning. This includes institutional parameters

such as (1) executive commitment; (2) technological infrastructures; (3)

student services; (4) design and development; (5) instruction and instructor

services; (6) program delivery; (7) financial health; (8) legal and regulatory

requirements; and, (9) program evaluation.

Holistic approach to QA began to develop since QA encompasses all aspects

of education. For e-learning development and delivery, Abdous (2009)

proposed a framework to enable institutions of higher learning to integrate

QA into e-learning development and delivery using a life-cycle model. Jara

and Mellar (2009) presented the results of case studies that looked into the way HEIs in the UK apply internal QA procedures in their e-learning courses.

It was found that the organizational position of the courses, distributed

configuration of course teams, disaggregated processes that characterize

e-learning, distant location of students were major factors that impact on

QA at the course level. QA also accounts for the roles and perspectives of stakeholders (e.g.,students, faculty, and administrators), as pointed out by Garcell et al. (2007). They further argued that agreements on quality standards among the different constituencies are the responsibility of the institution.

Kunz and Cheek (2016) traced the efforts to address QA for online offerings

in higher education over the past decade and reviewed the current position

of the online venue in higher education. Through examining the increase

in online education and how Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of

Business (AACSB)-Accredited Business Schools have been addressed, they

have concluded that online education will grow and increase its demand for

quality. Therefore, professional development programs must develop quickly

through the inclusion of effective instructional techniques, assignments,

assessment tools and activities. In simple terms, universities must learn to

adapt.

Currently, there are already a number of accrediting bodies, institutes,

consortiums, and trade associations for distance learning in higher

education worldwide. With the common goal of ensuring quality in DE, they

are the ones in-charge of developing sets of standards, criteria, guidelines,

or benchmarks which may vary in terms of their “scope, depth, emphasis,

and review components” (Southard & Mooney, 2015, p. 56).

Ossiannilson et al. (2015) under the International Council for Open and

Distance Education (ICDE) project, provided an overview of the existing

standards, guidelines and benchmarks for quality in open, distance, flexible

and online education, including e-learning and analysis was done among the

quality systems. In the report, findings of the study were further divided into

quality spectrum, quality standard models, quality matrix, characteristics

of quality systems, nature of quality interventions, and stakeholder

perspectives.

Quality spectrum discusses quality as a concept that can be viewed from

three levels—macro (national/global dimensions), meso (institutional matters), and micro (course/module). It can also be categorised based on Software Engineering Institute’s Competency Maturity Model’s (SEI-CMM) five levels—state, repeatable, defined, managed, optimized. In addition, quality systems can be further characterized whether they are accreditation-based systems, norm-based systems, maintenance of standards, QA-based systems, or mature enhancement-based systems. Quality standard models were found to be mostly related to these three to six main dimensions: staff support (services), student support (services), curriculum design (products),

course design (products), course delivery (products), and strategic planning

and development (management).

Quality matrix classified the quality standard models reviewed based on

what it covers, target groups, scope, intended use, and authority body. The

characteristics of quality systems in the field are found to be multifaceted,

dynamic, mainstreamed, representative, and multifunctional. In terms of

the nature of quality interventions, the institution’s maturity with e-learning

processes was found to be the determining factor of the type of quality

system applied or the way in which the quality system is applied. Stages in

the matrix are categorized as initial/early stage, developing, mature, and

evolving.

In essence, most of the systems reviewed gave importance to a holistic

approach in dealing with quality, even though some of the accreditation

systems give emphasis on baseline staffing and resource requirements.

A variety of quality tools has been created depending on the context to

which it can be applied. There has been no gap in terms of analysis of

institutional systems, but all quality systems suffer certain deficiencies.

Lastly, the report recommended that there is a need to provide a register of

good quality systems and a guide, addressing common issues for providers

of quality systems, provide a harmonized regulatory environment ensured

by international organizations, and an assured engagement of students in

determining quality standards by international organizations.

Despite the development of these QA initiatives, open and distance education is still somehow seen by the public as being of lower quality than that of traditional education (Hope, 2014). This could be partly driven by the fact that a number of governments have yet to develop a national policy for QA in DE, and that QA is not fully integrated yet into the planning and operations of DE institutions (Jung, 2013). In addition, technological

disruptions have impacted the educational landscape in recent years, which in turn have presented new challenges to conceptualizing and measuring quality in ODL. Below, we present some universal declarations and review major disruptions that impact quality issues in the field of education.

The right to education is one of the basic rights of a person and is an integral part in the plan of action or development of a specific area—whether in the international, regional, or national level. One of the earliest recognition of the right to education was promulgated in 1948 under Article 26 of the General Assembly Resolution 217-A entitled, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations [UN], n.d.a). This declaration had become the basis of any educational reforms in the world, such as the World Declaration on Education for All (EFA) (UNESCO, 1990) and the United Nations 2030 Agenda on Education for Sustainable Development (specifically the Sustainable

Development Goal [SDG] 4) in 1990 and 2015, respectively (UN, n.d.b). The EFA and SDG present an expanded version of the UN Declaration in consideration of the current global needs and situation. Both international declarations not only promote equitable access to quality education and lifelong learning but also identify the necessary support services needed in the pursuit of their respective goals.

In support of the international declarations on education, the ASEAN formulated its work plan on education for 2016-2020 aligned with the SDG 4 of “inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (Lanceta, n.d., slide 11). The work plan covers the SDG targets in terms of equitable access to quality education at all levels, enhancement/development of one’s understanding towards socio-cultural aspects through education, and education support services such as facilities, scholarships, and human resources (teachers).

Given that the promotion of equitable access to quality education and lifelong learning has already been promulgated through these declarations, achieving these goals lies in the active participation of the stakeholders involved. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2012) stated that the “highest performing education systems are those that combine quality with equity” (p. 3), in which equity in education is defined in terms of fairness and inclusion. Hence, educational institutions continuously

aim for academic excellence and equity even in the presence of educational reforms accompanied by changes in learning approaches and technological advances. In recent years, these disruptions, which include the arrival of Industrial Revolution 4.0, the inception of Web 4.0, and the eventual emergence of Education 4.0, have likewise given rise to new challenges and issues that traditional and open and distance education institutions have to face in its pursuit of quality.

The fourth industrial revolution or IR 4.0 is marked by technological breakthroughs that bring together the physical, digital, and biological spheres (Schwab, 2014) and is characterized by “deep integration of intelligence and networking system” (Zhang, 2014 as cited in Guoping et al., 2017, p. 626). Guoping et al. (2017) enumerated the technological drivers that prompted the IR 4.0. These are the internet of things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, big data and cloud computing, and digital platform for digital drivers; the autonomous cars and 3D printing for physical drivers; and the genetic engineering and neurotechnology for biological drivers.While the authors have mainly discussed the industrial (manufacturing) and economic implications and coping strategies, they acknowledge that IR 4.0 has an impact in “all aspects of the society” (Guoping et al., 2017, p. 627), which includes the education sector.

The developments in the World Wide Web (WWW) was also seen as one of

the disruptions affecting the educational landscape. The web had developed

from the Web 1.0 or the “read-only” web to the most recent Web 4.0. As a

recent development, it is known for its several definitions, among others,

being the “ultra-intelligent electronic agent, symbiotic web, ubiquitous web,

and read-write-execution-concurrency” driven by the synergistic interaction

between humans and machines (Choudhury, 2014).

Given such advancements, Demartini and Bennusi (2017) profiled the

evolution of education. Compared to Education 1.0 to 3.0, Education 4.0

will be relying more on AI applications in terms of the different attributes of

education – teacher, content delivery, learning process, learning organization,

student, and means. The emerging era of education, Education 4.0, gives

us a profile of the current or possible educational reforms that are currently

happening or may happen in the near future. These reforms call forth

quality, as a moving target, to advance its direction giving rise to new issues of equity and quality.

Due to realities brought about by shifting paradigms and technological advancements, some emergent issues come to the fore which, we argue, have to be at least in our consciousness as we conceptualize and operationalize quality in the realm of education. Based on a cursory review of the literature as well as experiences on the ground the following general issues are forwarded. Issues on massification, including open admissions and reaching out to marginalized groups, could have implications on quality.

Similarly, issues on digital inclusion is seen to have ramifications not just on equity but also on quality. In a networked environment as in IR 4.0, in a symbiotic web as in Web 4.0, and given the affordances of AI in Education 4.0, stakeholder requirements that determine quality in education have likewise to be considered. Massification was known to develop from the concepts of globalization and internationalization and has forced higher learning institutions to adapt to the challenges and opportunities that come with it (Bamdas, 2014; Altbach et al., 2009). In terms of post-secondary education, massification generally pertains to widening access (Kajubi, 1997 as cited in Lam, 2020). Altbach et al. (2009) noted that widening access to higher education had challenged universities on quality concerns (teaching, learning, and management).

As an example, open admission allows multiple entry and exit levels to students that were not necessarily the target recipient. Weller (2014) noted that open education does not cater to the marginalized group as statistics showed that the majority of massive open online courses (MOOCs) and open educational resources (OERs) users are experienced learners, well-educated, well-qualified, employed informal and formal learners.

On the other hand, massification also denotes the condition of a decline in quality and standards when the class number is not complemented by the availability of

educational resources (Mohamedbhai, 2008, as cited in Lam, 2020). Additionally, it has consequential quality issues such as increase in attrition rate as ODeL institutions have lower retention rates than campus-based education. Such is caused by additional external pressures and academic reasons. Thus, it is argued that students in ODeL enroll for courses to meet their particular needs, which can be their general interest or in connection to their profession. It was also emphasized that student success or failure

does not necessarily equate to the quality of the university or its students but it denotes the risks and challenges of openness and inclusion (Gaskell & Mills, 2014). Similarly, Naidu (2017) noted that one of the challenges faced by an open educational environment is student persistence and/or attrition which is attributed to “the minimalist nature of this form of educational provision and learning goals and aspirations of students”(p. 2).

Although expanding access to online education has been a promising move of educational institutions, literature has shown that it is not sufficient to address equity and quality concerns. Willems and Bossu (2012) critically evaluated OERs and argued that OERs do not always support equity as there have been access issues that continue to emerge from the implementation of OERs. Primary issues in adopting OERs include “the language of instruction, contextualization and localization, technological applications, and access in regional and remote regions around the globe”(p. 186). Other issues on the adoption of OERs include cultural and institutional issues such

as intellectual property rights and insufficient financial and support staff provision; the questionable quality as OERs are provided for free; and the one-way collaborative development (Willems & Bossu, 2012). In efforts to provide an understanding and future directions of open education ecosystems, Zhang et al. (2020) examined several OER and open educational practice (OEP) literature in relation to the accessibility

and functional diversity that is aligned with the equity aspect of SDG 4.

The authors encourage the researchers, educators, and practitioners to generate studies on the use and effectiveness of OER and OEP, to “develop authoring tools with features to create accessible content”, and to “consider different accessibility guidelines while developing their OER platforms, tools, and devices” (p. 16). Apart from massification, digital inclusion is another concern relevant to the stakeholders of e-learning institutions as it is the means for quality teaching and learning management. Bull and Brown’s (2012, as cited in Weller, 2014) study in Australia documented that technology access is lacking for those who really need access to higher education. Nonetheless, access was considered to be a major issue in DE especially for countries struggling with poor infrastructure in terms of internet access and postal services (Gaskell & Mills, 2014). In addition, OERs must be accompanied by actions in providing digital access that goes beyond physical tools, which means digital content and digital literacy must be accounted for as well (Bandalaria, n.d.). One of the characteristics of digital access was digital content which considers the educational context of students. Contextualization in education, specifically in OERs produced, not only involves the consideration of language to be used but also socio-cultural factors. A study of Mittelmeier et al. (2018) that assessed the applicability of the Open University Learning Design (OULD) of the Open University of the United Kingdom in a diverse context, arrived at a suggestion to incorporate locally-relevant content which is also seen as an important factor to produce graduates who are productive members of their own society. Correspondingly, it was noted that there is aneed for OERs to be translated to local language and be contextualized to local culture and dynamics (UPOU Networks, n.d.).

Solutions to these barriers may include tapping telecommunication companies, academic and government institutions to provide training on digital literacy especially with the marginalized sectors of society; making digital content available in various format by integrating Web Content Accessibility Guidelines or WCAG in online platforms to address the needs of physically-challenged individuals; and policies that can mobilize resources and facilitate implementation of concrete programs to remove the barriers

(Bandalaria, n.d.). Another approach to be considered in allowing local dynamics to be inculcated in OERs is the concept of personalization. An article by Aoki (2013) emphasized the importance of a shared database of learners in establishing a personalized learning environment, data mining, and QA or enhancement of an institution. However, the personalization of learners is only possible through appropriate learning analytics and data mining of the big data gathered from the learners.

Lastly, quality in education is also determined by the needs and requirements of various stakeholders. Wagner et al. (2008) indicated that the success of e-learning in higher education is dependent on how the needs and concerns of stakeholder groups are addressed by e-learning institutions. Similarly, Primrose et al. (2013) emphasized that ODL stakeholders are important in the improvement of educational quality. However, in a disruption era, these requirements adjust as the stakeholders adapt to new changes brought by technological advancements. Hence, educational institutions must likewise, keep pace with the technological changes to match the stakeholders’ needs and requirements. This will require an extensive stakeholders’ consultation as well as adjustments in the QA systems and processes.

Beyond identifying emerging quality concerns is the struggle to address and integrate it in a QA framework. However, for open educational institutions, such concern is coupled by the lack of a QA framework that is suitable in its context. Majority of the existing QA frameworks are challenged by technological advances (Mabuza, 2014), therefore deemed inappropriate for open education institutions whose operation is grounded by the affordances of ICTs. In addition, the lack of quality models in Asia was documented by consolidating the most used quality models in DE and e-learning (Ossiannilsson, 2015). This is further supplemented by a regional report conducted by Mathes (2018) under the ICDE claiming that there is a “lack of QA instrument and framework specifically designed for DE and online learning in Asia and existing government QA frameworks for higher education do not specifically address distance and online learning” (p. 8).

Tracing back the concepts and issues of quality and QA gives an overview of the position of ODL and ODeL institutions in quality education. While there are efforts demonstrating quality in online learning, these are often disconnected and not integrated into a holistic framework. However, the need to assure that quality education is being provided, albeit the lack of a QA framework, poses a challenging situation, especially in the presence of the changing education landscape caused by disruptions and growing demand for online learning.

model. Quality Assurance in Education, 17(3), 281–295. http://doi.

org/10.1108/09684880910970678

Allais, S. M. (2009). Quality assurance in education. Issues in education policy,

5. Centre for Educational Policy Development.

Altbach P., Resiberg L., & Rumbley L. (2009). Trends in global higher education:

Tracking an academic revolution. United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://www.cep.edu.rs/public/Altbach,_Reisberg,_Rumbley_Tracking_an_Academic_ Revolution,_UNESCO_2009.pdf

Aoki, K. (2013, June 06). Paradoxes between personalisation and massification

[Paper Presentation]. International Conference on the Future of

Education 2013, Florence, Italy. https://conference.pixel-online.net/

conferences/foe2013/common/download/Paper_pdf/197-ENT14-

FP-Aoki-FOE2013.pdf

ASEAN University Network. (2015). Guide to AUN-QA assessment at

programme level version 3.0. http://www.aunsec.org/pdf/Guide%20

to%20AUN-QA%20Assessment%20at%20Programme%20Level%20

Version%203_2015.pdf

ASEAN University Network. (2016). Guide to AUN-QA assessment at institutional

level version 2.0. http://aun-qa.org/views/front/pdf/publication/

Guide%20to%20AUNQA%20Assessment%20at%20Institutional%20

Level%20Version2.0_Final_for_publishing_2016%20(1).pdf

Asian Association of Open Universities. (n.d). Quality assurance framework.

Asian Association of Open Universities. (2011). AAOU annual report 2020.

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. (2019). Quality assurance of online learning toolkit. https://www.apec.org/Publications/2019/12/APEC-Quality-Assurance-of-Online-Learning-Toolkit

Belawati, T., & Zuhairi, A. (2007). The practice of a quality assurance system

in open and distance learning: A case study at Universitas Terbuka

Indonesia (the Indonesia Open University). International Review

of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 8(1). https://search.

proquest.com/docview/1634488781?accountid=47253

Choudhary, N. (2014). World wide web and its journey from web 1.0 to web

4.0. International Journal of Computer Science and Information

Technologies, 5(6), 8096–8100. http://ijcsit.com/docs/

Volume%205/vol5issue06/ijcsit20140506265.pdf

Commonwealth of Learning. (2019). The regional community of practice (CoP)

quality assurance guidelines in Open and Distance Learning (ODL).

http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/3126

Darojat, O., Nilson, M., & Kaufman, D. (2015). Perspectives on quality and

quality assurance in learner support areas at three Southeast Asian

open universities. Distance Education, 36(3), 383–399. https://doi.

org/10.1080/01587919.2015.1081734

Demartini, C., & Benussi, L. (2017). Do Web 4.0 and Industry 4.0 Imply

Education X.0? IT Professional, 19(3), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/

MITP.2017.47

Friend-Pereira J.C., Lutz K., & Heerens N.. (2002). European Student Handbook

on Quality Assurance in Higher Education. ESIB – The National Unions

of Students in Europe. http://www3.uma.pt/jcmarques/docs/info/

qaheducation.pdf

Frydenberg, J. (2002). Quality standards in e-learning: A matrix of analysis. The

International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning,

3(2), 1–15 . https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v3i2.109

Garcell, E., García, M. R., Glogauer, N., & Hobson, D. (2007).

Quality in distance education: A triple perspective. Distance

Learning, 4(4), 19–28. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/

download?doi=10.1.1.364.445&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Gaskell, A., & Mills, R. (2014). The quality and reputation of open, distance

and e-learning: What are the challenges? Open Learning, 29(3), 190–

205. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2014.993603

Guoping L., Yun H., & Aizhi W. (2017). Fourth industrial revolution: Technological

drivers, impacts and coping methods. Chinese Geographical Science,

27(4), 626–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-017-0890-x

Harvey, L. (2005). A history and critique of quality evaluation in the UK.

Quality Assurance in Education, 13(4), 263–276. https://doi.

org/10.1108/09684880510700608

Hope, A. (2014). Review of quality assurance in distance education and

elearning: Challenges and solutions from Asia. Open Learning, 29 (1),

86–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2014.882254

Jara, M., & Mellar, H. (2009). Factors affecting quality enhancement

procedures for e-learning courses. Quality Assurance in Education,

17(3), 220-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684880910970632

Jung, I. (2007). Changing faces of open and distance learning in Asia.

International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning,

8(1). https://dx.doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v8i1.418

Jung, I. (2013). Concluding remarks: Future policy directions. In Jung, I. Wong,

T.M. & Belawati, T. (Eds.), Quality assurance in distance education

and elearning: Challenges and solutions from Asia (pp. 275-

288). International Development Research Centre. https://dx.doi.

org/10.4135/9788132114079

Kanwar, A. (2013). Foreword. In Jung, I. Wong, T.M. & Belawati, T. (Eds.),

Quality assurance in distance education and elearning: Challenges

and solutions from Asia (pp. xxi–xxiv). International Development

Research Centre. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9788132114079

Kidney, G., Cummings, L., & Boehm, A. (2007). Toward a quality assurance

approach to e-learning courses. International Journal on E-Learning,

6(1), 17–30. https://www.learntechlib.org/j/IJEL/

Kunz, M. B., & Cheek, R. G. (2016). How AACSB-accredited business schools

assure quality online education. Academy of Business Journal, 1(1),

105–115. https://search.proquest.com/openview/ad22a76e32574

ca3cd27f1cb07fd918c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2044545

Lam, J. L. (2020). ICT in teaching and learning and management of

massification. In D.Z. Atimuni (Ed.), Postgraduate research

engagement in low resource settings (pp. 16–35). IGI Global. https://

dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-0264-8.ch002

Lanceta A. (n.d.). ASEAN Cooperation on education and the SDG 4 [Powerpoint

slides]. https://bangkok.unesco.org/sites/default/files/assets/ article/Education/files/session-2asean-cooperation-education-

sdg-4.pdf

Mabuza, L. (2014). Unpacking quality assurance issues in distance

education, using the University of South Africa, a mega open

distance learning university as an example. International Journal of

Information and Education Technology, 4(6), 513. http://ijiet.org/

papers/461-H00005.pdf

Mathes, J. (2019). Global quality in online, open, flexible and technology

enhanced education: An analysis of strengths, weaknesses,

opportunities and threats. International Council for Open and Distance Education. https://www.icde.org/knowledge-hub/report-

global-quality-in-online-education

Mittelmeier, J., Long, D., Cin, F., Reedy, K., Gunter, A., Raghuram, P., &

Rienties, B. (2018). Learning design in diverse institutional and

cultural contexts: Suggestions from a participatory workshop with

higher education professionals in Africa. Open Learning: The Journal

of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 33(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/

10.1080/02680513.2018.1486185

Mills, R. (2006). Quality assurance in distance education – Towards a culture of

quality: A case study of the Open University, United Kingdom (OUUK).

In B.N. Koul, & A. Kanwar (Eds.), Perspective on distance education:

Towards a culture of quality (pp. 135–148). Commonwealth of

Learning.

Mishra, S. (2007). Quality assurance in higher education: An introduction.

National Assessment and Accreditation Council, India.

Naidu, S. (2017). Openness and flexibility are the norm, but what are the

challenges? [Editorial]. Distance Education 38(1), 1–4. https://doi.or

g/10.1080/01587919.2017.1297185

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2012). Equity and

quality in education: Supporting disadvantaged students and schools.

OECD Publishing. http://doi.org/10.1787/9789264130852-en

Ossiannilsson,

E., Williams, K., Camilleri, A. F., & Brown, M. (2015). Quality

models in online and open education around the globe. State of the art

and recommendations. International Council for Open and Distance

Education. https://www.pedocs.de/frontdoor.php?la=de&source_

opus=10879

Primrose, K., Paul, M., & Chrispen, C. (2013). Unmasking the role of

collaboration and partnerships in open and distance learning systems.

World Journal of Management and Behavioral Studies 1(2), 36–43.

Rama, K., & Hope A. (Eds.). (2009). Quality assurance toolkit for distance

higher education institutions and programmes. Commonwealth

of Learning. https://open.saide.ngo/repository/opensaide/1.%20

COL%20HE_QA_Toolkit_web.pdf

Reisberg, L. (2010, April 12–15). Quality assurance in higher education:

defining, measuring, improving it [Powerpoint presentation]. University

Center of Boston for International Higher Education. http://www.

gr.unicamp.br/ceav/pdf/unicamp_qa_day1_final[1].pdf

Schindler, L., Puls-Elvidge, S., Welzant, H., & Crawford, L. (2015). Definitions

of quality in higher education: A synthesis of the literature. Higher

Learning Research Communications, 5(3), 3–13. http://doi.

org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i3.244

Southard, S., & Mooney, M. (2015). A comparative analysis of distance

education in quality assurance standards. Quarterly Review of

Distance Education, 16(1), 55–68. https://go.gale.com/ps/

Stella, A. & Gnanam, A. (2004). Quality assurance in distance education:

The challenges to be addressed. Higher Education, 47(2), 143–160.

http://doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000016420.17251.5c

Thurab-Nkhosi, D., & Stewart, M. (2009). Quality management in course

development and delivery at the University of the West Indies Distance

Education Centre. Quality Assurance in Education, 17(3), 264–280.

http://doi.org/10.1108/09684880910970669

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (1990).

World declaration on education for all and framework for action to

meet basic learning needs. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/

pf0000127583

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (1998,

October 9). World declaration on higher education for the twenty-first

century: Vision and action and framework for priority action for change

and development in higher education [Conference Session]. World

Conference on Higher Education Higher Education in the Twenty-First

Century: Vision and Action, Paris, France. https://unesdoc.unesco.

org/ark:/48223/pf0000141952

United Nations. (n.d.a). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.

un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

United Nations. (n.d.b). Take action for the sustainable development goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-

development-goals/

UPOU Networks. (n.d.). Digital access beyond the physical tools by Melinda dP Bandalaria [Video]. https://networks.upou.edu.ph/23285/digital-

access-beyond-the-physical-tools-dr-melinda-dp-bandalaria/

Vidovich, L. (2001). That chameleon ‘quality’: The multiple and contradictory

discourses of quality policy in Australian higher education. Discourse:

Studies in the cultural politics of education, 22(2), 249–261. https://

doi.org/10.1080/01596300120072400

Wagner, N., Hassanein, K., & Head, M. (2008). Who is responsible for

e-learning success in higher education? A stakeholders’ analysis.

Educational Technology & Society, 11(3), 26–36. https://www.

researchgate.net/publication/220374509_Who_is_Responsible_

for_E-Learning_Success_in_Higher_Education_A_Stakeholders’_

Analysis/link/541ff6340cf2218008d42655/download

Willems, J., & Bossu, C. (2012). Equity considerations for open educational

resources in the glocalization of education. Distance Education,

33(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.692051

Weller, M. (2014). The battle for open: How openness won and why it doesn’t

feel like victory. Ubiquity Press. https://doi.org/10.5334/bam

Schwab, K. (2016, January 04). The fourth industrial revolution What it means,

how to respond. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/

about/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-by-klaus-schwab

Zhang, X., Tlili, A., Nascimbeni, F., Burgos D., Huang, R., Chang, T., Jemni, M., &

Khribi, M. (2020). Accessibility within open educational resources and

practices for disabled learners: A systematic literature review. Smart

Learning Environments 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-019-

0113-2

Lumanta, M. F., Garcia, P. G., Lapitan, A. S., Ortiguero, I. G. (2020). Situating Quality Concepts, Issues, and Measures in Open and Distance Education. In Quality Initiatives in an Open and Distance e-Learning Institution: Towards Excellence and Equity (pp. 1-22). Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Open University