In recent years, there have been calls to incorporate access and equity into quality assurance (QA) frameworks of higher education institutions. Open and distance learning (ODL) institutions have been at the forefront of developing QA frameworks with openness in mind. This chapter discusses how equity of access can be achieved by ensuring that educational opportunities are not only made available to learners but also prepares them to take advantage of such opportunities.

Ensuring quality in education is considered essential in creating sustainable development (United Nations [UN], n.d.), but how quality education is defined and measured varies. The concept of quality is hard and “impossible to define with any degree of universal agreement” (Fallows & Bhanot, 2005, p.1). So far, there is no single definition for quality education that is universally accepted. The notions and standards of quality education are evolving (Pigozzi, 2006). Universities and academic institutions have different ways to measure quality. Ranking appears to be “a simple and easy way to measure and compare performance and productivity” and is claimed to be the ultimate measure of higher education quality; however, global and international rankings are guided by limited indicators, and these may not be appropriate for some conditions and instances as there may be different notions of quality across nations and cultures (Hazelkorn, 2013, Why Rankings section). Some major university rankings, such as the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) and the Times Higher Education (THE), mainly focus on “quality of teaching and quality of research” but fail to incorporate the “service to society” aspect in their quality indicators (Lalic, 2017, para. 3 & 4).

Quality seems “based more on what institutions do, rather than what they are called” (Hazelkorn, 2013, “Because rankings” section). Quality and excellence are regarded as “the main drivers impacting on and affecting higher education, nationally and globally” (Pursuing Quality section), but “which university is best depends upon who is asking the question, what question is being asked”, and why it is being asked, because higher education systems from different societies may have different priorities, thus producing different results depending on what is being measured, and for what purpose (Hazelkorn, 2013, What is Quality section). Existing side by side with the discourse of quality in education is the discourse of equity of access to education. The world we live in is fast-changing, and there is a greater expectation for higher education to respond responsibly to these challenges. It is no longer enough that higher education is of quality, it has to be accessible as well. Globalization has increased the mobility of goods, people, and ideas. While it has spurred economies for a period of time, its unintended consequences are also more apparent now more than ever—slow economic growth, deteriorating inequality between the haves and the have nots, environmental degradation, and the list goes on.

More than ever, education is being seen as “an important vehicle through which economically and socially marginalized adults and children can be empowered to change their life chances, and obtain the means to participate more fully in their communities” (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2005a, p. 28). As people become more mobile, universities are expected to make their education more accessible to different types of learners in different parts of the country and the world. As traditional industries die and new industries arise, the value of re-skilling and consequently lifelong learning becomes more apparent. As workers move from one part of the country or the world to another, the accreditation of educational qualifications across borders becomes more salient. Open and distance learning (ODL) institutions have been in the business of providing accessible education in the past several decades. By adopting technologies to connect teachers and learners, ODL institutions have conquered the tyranny of time and distance in learning. Many ODL institutions have also taken advantage of the affordances of e-learning to enhance the quality of their academic offerings. In recent years, many conventional universities have seen the affordances offered by distance education, including blended learning, in reaching more diverse sets of learners. To ensure the quality of programs, ODL institutions have developed their own quality assurance (QA) frameworks, with special emphasis on ensuring that barriers to effective participation of learners in the university are addressed. While ODL institutions have contributed to making education more accessible to vast numbers of people, there is this pervading yet outmoded notion that access/equity can somehow diminish the quality of higher education. The continuing emphasis by universities on student selectivity in admissions tends to imply that access dilutes quality. In this chapter though, the authors would argue that equity of access and quality in education are not incompatible. Using McCowan’s three dimensions of equity, we shall also discuss the implications of adopting equity of access to quality frameworks. We shall elaborate this idea by looking at the experiences of the University of the Philippines Open University (UPOU) in open and distance e-learning (ODeL).

The relationship between access and quality is not exactly a new idea. Despite varying notions of quality at the level of international debate and action, these three principles tend to be broadly shared: the need for more relevance, for greater equity of access and outcome, and for proper observance of individual rights (UNESCO, 2005b).

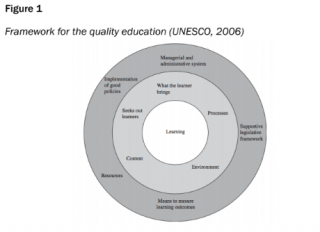

UNESCO cited the dimensions of quality as follows: learners, environments, content, processes, and outcomes, founded on “the rights of the whole child, and all children, to survival, protection, development and participation” (UNICEF, 2000, p. 4), managerial and administrative system, implementation of good policies, supportive legislative framework, resources, and means to measure learning outcomes (Pigozzi, 2006) (see Figure 1).

UNESCO (1998) has referred to quality in higher education as a “multidimensional concept” that encompasses all academic functions and services ranging from “teaching and academic programmes, research and scholarship, staffing, students, facilities, faculties, and services to the community and the academic environment” (Lumanta & Carascal, 2018, p. 184).

For higher education institutions (HEIs) in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) context, the ASEAN University Network (AUN) developed the AUN-Quality Assurance (AUN-QA) Framework which focuses on assessment at the programme and institutional levels (ASEAN University Network, 2016, as cited in Lumanta & Carascal, 2018). The third version of programme level assessment constitutes a total of 11 criteria which include: Expected Learning Outcomes; Programme Specification; Programme Structure and Content; Teaching and Learning Approach; Student Assessment; Academic Staff Quality; Support Staff Quality; Student Quality and Support; Facilities

and Infrastructure; Quality Enhancement; and Output (AUN, 2015).

The second version of institutional level assessment, on the other hand, constitutes a total of 25 criteria which include the following: Vision, Mission, and Culture; Governance; Leadership and Management; Strategic Management; Policies for Education, Research, and Service; Human Resources Management; Financial and Physical Resources Management; External Relations and Networks; Internal Quality Assurance (IQA) System; Internal and External QA Assessment; IQA Information System; Quality Enhancement; Student Recruitment and Admission; Curriculum Design and Review; Teaching and Learning; Student Assessment; Student Services and Support; Research Management; Intellectual Property Management; Research Collaboration and Partnerships; Community Engagement and Service; Educational Results; Research Results; Service Results; and Financial and Market Results (AUN, 2016).

Universities have traditionally been the purview of religious organizations and catered mostly the education of the social elites in the West. In the late 19th century, national states began setting up publicly funded universities to make it more accessible to their citizens. While access to universities has increased over centuries, the concept of open access can be traced back historically to the University External System established by the British government to educate its citizens living all over its empire. Formally speaking, the discourse of openness has been formally linked to the establishment of the United Kingdom (UK) Open University in 1965. Since then, many open universities have been established in different parts of the world to make education accessible, especially to people who cannot access it due to constraints posed by geography, time, economic conditions, etc. These universities have attempted to break down these barriers by adopting the philosophy of openness and the methods of distance learning. ODL is considered “a promising and practical strategy to address the challenge of widening access thus increasing participation in higher education” (Pityana, 2009 as cited by Letseka & Pitsoe, 2012, p. 221).

The ODL, through the use of technologies, such as radio, television, print media, and internet, plays an important role in bridging the gap between the teacher and the learners, giving more flexibility, access, and equity in a learning environment. ODL provides more access to education to more people, who are being denied access to education based on race, religion, language, ethnicity, age, socio-economic status, gender, culture, physical or intellectual capacities, etc. Through ODL, equal access to education is being promoted, thus minimizing inequity relating to gender, income, region, socio-cultural-related, and others. While open universities have made huge strides in making education more accessible to a vast number of people, questions have been raised about the quality of its programs. To address, ODL institutions have developed their own QA frameworks. For open universities in Asia, there is the Asian Association of Open Universities (AAOU) QA Framework (Belawati & Zuhairi, 2007; Darojat, et al., 2015 as cited in Lumanta & Carascal, 2018). The framework sets out important guidelines for each of the ten strategic issues identified in the distance education system: Policy and Planning; Internal Management; Learners and Learners’ Profiles; Infrastructure, Media, and Learning Resources; Learner Assessment and Evaluation; Research and Community Services; Human Resources; Learner Support; Programme Design and Curriculum Development; and Course Design and Development (AAOU, n.d.).

• Policy and Planning. In this component, an ODL institution is expected to have well-defined vision and mission, goals, policies, and strategies; a well-designed monitoring and evaluation system; and a clear policy statement of non-discriminatory stakeholder’s participation and commitment to learners.

• Internal Management. This component looks at the quality, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness in the management and operations of an ODL institution, including its marketing and promotion system, management system for institution and learning, communication system and decision making, student services system, infrastructure and facilities, and internal QA system.

• Learners and Learners’ Profile. This component emphasizes the need to ensure learners’ awareness of an ODL institution’s courses and programs; confidentiality of learners’ database; sufficiency of information on learners’ expectations and profile that may be used in designing learner-centered programs and support services; and provision of learner support services, especially for those who belong to disadvantaged groups.

• Infrastructure, Media, and Learning Resources. In this component, an ODL institution is expected to use a variety of media and technologies that are appropriate, accessible, equitable, and practical. Moreover, this component suggests that adequate training and support for those who will use these media and technologies should be provided. An ODL institution should also undertake research and development related to the use of new technology.

• Learner Assessment and Evaluation. This component suggests an effective assessment of student learning by looking at an ODL institution’s policy on assessment, planning and production of assessment materials, assessment administration, and assessment results processing, dissemination, and utilization.

• Research and Community Services. This component focuses on an ODL institution’s research support system and community service support system, specifically on the sufficiency of qualified staff members and resources for its research projects and its contribution to the community through the promotion and provision of lifelong education.

• Human Resources. In this component, an ODL institution is expected to have sufficient qualified and competent staff members. It should provide a well-defined performance management system and a career development plan for its staff members. Moreover, it should equip its staff members with necessary job skills through training and development programs.

• Learner Support. This component acknowledges the importance of providing learner support services, such as tutorial and counseling, at a distance through the use of various forms of technology.

• Programme Design and Curriculum Development. In this component, an ODL institution is expected to have specific needs assessment and qualified experts and to consider stakeholders’ interests in programme design and curriculum development.

• Course Design and Development. This component is concerned with the effectiveness of courses offered by an ODL institution in meeting the learners’ needs by looking at its courses’ design. It considers the consistency of course content and learning activities and assessments, the clarity of course objectives, the integration of course design with the learning support services, the availability of effective course evaluation system, and the sufficiency of professional and technical support for staff members involved in course design and development.

Currently, the AAOU Accreditation Task Force is developing an accreditation system for open distance education that is targeted to be used in Asian countries and even worldwide. This is an initiative of UPOU Chancellor Dr. Melinda Bandalaria as the AAOU President and Dr. Grace Alfonso as the AAOU Secretary-General from 2017 to 2019. The project aims to ensure the quality of all forms of technology-mediated education as well as to strengthen the image of ODL institutions. The pilot run of the accreditation instrument is planned to be conducted in 2020. There are a number of parallelisms between the QA system of AAOU and the AUN. Both take on a systems perspective of quality, emphasizing the quality of inputs, throughputs, and outputs to ensure the quality of academic programs. In the AAOU QA framework, there is more emphasis on the learners’ profile to ensure that the way teaching and learning is administered to suit the needs and requirements of distance learners.

ICDE QA Initiatives

The International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE) is “the leading, global membership organization that works towards bringing accessible, quality education to all through online, open and distance learning” (ICDE, n.d., “Who We Are” section). With almost 200 higher education and research institutions in over 70 countries and almost 20 organizations around the world, the ICDE aims to contribute to the achievement of the SDG 4, which targets to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.

The ICDE continually builds global networks by facilitating partnerships and cross-border collaborations through events, specialist networks, projects,and task forces. One of these initiatives is the study that looked at different quality models in online and open education around the globe. From this study, the following recommendations were provided for stakeholders:

(1) mainstream e-learning quality into traditional institutional QA;

(2) support the contextualization of quality systems;

(3) support professional development, in particular through documentation of best practice and exchange of information;

(4) communicate and promote general principles;

(5) assist institutions in designing a personalized quality management system;

(6) address unbundling and the emergence of non-traditional educational providers;

(7) address quality issues around credentialization through qualifications frameworks;

(8) support knowledge transfer from ODL to traditional quality systems;

(9) support QA audits and benchmarking exercises in the field of online, open, flexible, e-learning and distance education;

(10) encourage, facilitate and support research and scholarship in the field of quality;

and (11) encourage, facilitate and support implementing QA related to new modes of teaching (Ossiannilsson et al., 2015).

Aside from this first global overview of quality models, the ICDE also created the ICDE Quality Network, in which the Focal Points on Quality (FPQs) were identified to lead and coordinate quality work in their respective regions (Mathes, 2018). This was developed not only to contribute to the SDG 4 but also to support UNESCO’s higher education initiatives in online, open and flexible learning. The ICDE also promotes the use of open educational resources (OERs) through its ICDE OER Advocacy Committee, which works to increase global recognition of OER and to provide policy support for the uptake, use, and reuse of OER. Another QA initiative from the ICDE is the creation of the ICDE Working Group, in which members are invited to submit an Expression of Interest for participating in the Working Group on the Present and Future of Alternative Digital Credentials. The ICDE also ensures the enhancement of quality of student support through its ICDE Quality Review Service.

Access to education has not been a recent pursuit. The urbanization of towns in the Middle Ages and technological innovation (i.e., invention of the printing press) and social and economic ferment of the Renaissance saw the increasing availability of reading materials to the general public (Peter & Deimann, 2013). Compulsory education was initiated in America in the 17th century and in European countries, like France and the United Kingdom, in the late 19th century. In the Philippines, the public school system was born in 1863, with the passage of the Education Reform Act in the Spanish Courts. It was expanded by the Americans with the arrival of the 600 American teachers called the Thomasites during the early days of U.S. colonization.

After experiencing the atrocities committed during the Second World War, the world worked to define human rights and reaffirmed its resolve to respect the dignity of the human person. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966 state that “education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit and individual capability”, and “access to education and learning outcomes should not be affected by circumstances outside of the control of individuals, such as gender, birthplace, ethnicity, religion, language, income, wealth or disability” (Chien & Huebler, 2018, p. 11).

Since then, accessible education has increasingly become a given—an inalienable right every person is entitled to. In 1990, UNESCO even declared the World Declaration on Education for All that promotes education as a right and discusses the role of education in personal and societal development which incorporates: (1) universalizing access and promoting equity to all ages, genders and groups; (2) focusing on learning and continued participation in organized programmes and completion of certification requirements; (3) broadening the means and scope of basic education; (4) enhancing the environment for learning; and (5) strengthening partnerships at national, regional and local levels. Article 3 of the 1990 World Declaration on Education on universalizing access and promoting equity emphasized that quality education should be provided equally to all ages, genders and groups, to reduce disparities, eliminate gender stereotyping, remove any discrimination in access to learning opportunities, and provide equal access to education (UNESCO, 1990). Also, article 5 of the same declaration,

pointed out the need to use a variety of delivery systems and all available instruments and channels of information, communications to convey essential knowledge, and to meet the diverse learning needs of youth and adults (UNESCO, 1990).

With the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Education 2030 Framework for Action in 2015, access to education “has been placed at the heart of the international development agenda”, aiming to “address all forms of exclusion and inequalities in access, participation, and learning outcomes, from early childhood to old age” (Chien & Huebler,2018, p. 11). The SDGs are the blueprint set by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015 for creating a better and sustainable future for all. Focusing on education, SDG 4 aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030” (UNESCO, n.d., para. 3), to address concerns such as: (1) lack of basic elements of a good quality education which are trained teachers and adequate facilities; and (2) low literacy rate involving adults and women.

The ASEAN, of which the Philippines is an active member, has declared its commitment to support the SDG 4 through the promotion of inclusive and equitable opportunities to quality education for all, school safety against disasters, and promote lifelong learning, pathways, equivalencies, and skills development and the use of information and communications technology (ICT).

In recent years, there have been initiatives to make higher education more accessible to Filipinos. The following laws were passed to support this thrust:

1. Republic Act No. 10931 (Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act, 2017)

Approved on the 3rd day of August 2017 is the Republic Act No. 10931, which is “an act promoting universal access to quality tertiary education by providing for free tuition and other school fees in state universities and colleges, local universities and colleges and state-run technical-vocational institutions, establishing the tertiary education subsidy and student loan program, strengthening the unified student financial assistance system for tertiary education.”

2. Republic Act No. 7277 (Magna Carta for Disabled Persons, 1992)

RA 7277 is “an act providing for the rehabilitation, self-development, and self-reliance of disabled persons and their integration into the mainstream of society and for other purposes”, which was approved on the 24th day of March 1992, includes the rights of disabled persons to access quality education.

3. Commission on Higher Education (CHED) Programs and Projects (CHED, n.d.)

In the Philippines, CHED has different programs and projects that help in promoting access and equity in higher education including Student Financial Assistance Programs (StuFAPs), QA Projects, Centers of Excellence and Centers of Development (COEs/CODs), Faculty Development Program (FacDev), Expanded Tertiary Education Equivalency and Accreditation (ETEEAP), Foreign Scholarship and Training Programs (FSTP), Research Development and Extension, National Agriculture and Fisheries Education System (NAFES), and International Collaborations.

4. Republic Act No. 10650 (Open Distance Learning Act, 2014)

Republic Act No. 10650 is “an act expanding access to educational services by institutionalizing open distance learning in levels of tertiary education.” Section 9, states that the mode of delivery of open distance learning (ODL) can be in the form of print, audio-visual, face-to-face sessions, and/or electronic/computer technology and virtual classrooms (e-learning) and section 12 includes the role of the UPOU in the implementation of ODL in the Philippines.

Over the centuries, there has been a move towards democratization of higher education. These efforts towards equity of access have been moving on two fronts—among conventional universities and among ODL universities. Conventional universities have been providing financial support and affirmative action to enable students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Alongside these efforts, ODL institutions have been pioneers addressing traditional barriers to higher education like geography, time, and admission requirements that discriminate against certain groups.

In recent years, e-learning has become an important tool for democratizing higher education. It has been adopted both by conventional universities as well as open universities (most of which started with the print modular or broadcast model of distance education) to further make their courses available to more people. But as McCowan 2016) has argued with his three dimensions of equity of access model, making the courses available does not automatically lead to accessibility given the existing unjust social structures that have prevented certain groups of learning from reaching as well as maximizing the benefits of such learning opportunities. As the experience of UPOU and other universities have shown, accessibility measures have to be put in place not only to encourage disadvantaged groups to avail of these learning opportunities but also to perform well in their academic work in the university.

Increased openness becomes more of a lip service if it is not accompanied by such initiatives. On the other hand, the adoption of e-learning as an instructional approach also adds another layer of complexity to the educational system. While it has opened up opportunities for access, it also becomes a barrier for others. Given that the internet infrastructure is a concern that cuts across many sectors, universities need to partner with other organizations in advocating for greater investments in ICT infrastructure particularly in the rural areas. The idea of horizontality suggests that greater opportunities for disadvantaged or non-traditional learners must not come at a cost of unevenness in the quality of education across the system. For access to be truly equitable, quality has to be maintained within a university and across universities/ educational institutions. While diversity across universities in terms of disciplinary focus or research priorities may exist and even encouraged, we cannot afford to have a system where there are “reputable” universities for the academically prepared and “other” universities for the disadvantaged.

Digital literacy, which comes along with e-learning or technology-enhanced instruction, should not be only for the benefit of the few. Accessibility is a concern that must cut across the higher educational system. Not only is diversity of learners socially beneficial for non-traditional learners, but it also benefits everyone since it allows for the sharing of diverse perspectives and experiences that give learners a more well-rounded view of the world they live in, so quality systems have to be maintained across the system. As educational institutions become more open and/or use e-learning to expand their reach, quality frameworks have to incorporate these principles and values as well. If higher education institutions are indeed committed to the cause of greater accessibility, they should consider educational outcomes, processes, and ultimately inputs that are associated with increased accessibility in their quality frameworks. The adoption of e-learning also augurs well for the use of learning analytics not only to monitor student performance but also to identify challenges faced by non-traditional students, benefits arising from learner diversity, and effects of accessibility measures on learner performance, etc. The key here is to make learning analytics actionable, so it becomes a tool not only for spotting problems and addressing them but also for demonstrating how equity of access could play out in an ODeL environment.

Promoting quality, access, and equity can enhance the quality of education. In this section, we shall discuss these three dimensions—availability, accessibility, and horizontality—and illustrate them by citing some initiatives of the UPOU. McCowan (2016) has argued that these dimensions must work together in ensuring fairness of access to higher education by providing sufficient opportunities with quality to all individuals who are interested and prepared regardless of their status and background.

1. Availability

Availability pertains to the sufficiency of opportunities to access quality higher education, which operationally refers to the “overall number of places available, as well as the existence of adequate facilities, teaching staff, and so forth” (McCowan, 2016, p. 657). These opportunities may include an overall number of avenues of learning, as well as facilities, resources, and teaching staff. McCowan (2016) pointed out that the concept of availability is not only about the existence of opportunities; these opportunities should be adequate for all who are “interested” and “prepared” to access higher education. This means that expansion of availability of opportunities does not have to mean providing “vacancies for 100% of each age cohort”; it means providing sufficient opportunities “for those people who are interested in studying at this level and who have the minimum level of preparation” (McCowan, 2016, p. 657). McCowan (2016) cited instances where the concept of availability is highlighted. In the case of students who are “inadequately prepared by their previous experiences of schooling”, “further free-of-charge preparatory

provision should be made available” (p. 659). For those people who may want to study at university at later stages in life, there should be available and easy re-entry points. Chipere (2017) suggested the use of freely available resources on the World Wide Web, including OERs like open textbooks (Weller, 2014) as a way to ensure that learning opportunities are available to all. Information related to offered courses and programs (such as educational goals), technical assistance, tutors (Marciniak, 2018; Priyogi et al., 2017), physical and digital libraries (Chapman & Henderson, 2010), sufficient finance, resources, and expertise (Altbach et al., 2009; Malik, 2015) are among the so-called “opportunities” that should also be available. The concept of availability does not only promote sufficiency of courses. Campos et al. (2017) argued that there should be diversity of courses available to students. Moreover, the resources made available to students should be of different types (Marciniak, 2018) to cater to various learning

styles. Let us illustrate the concept of availability by looking at UPOU as an example.

UPOU, by virtue of its mission, has sought to provide wider access to quality higher education. Before its establishment in 1995, learners can only access University of the Philippines (UP) education by getting admitted to any of its existing brick and mortar campuses. UPOU’s establishment has provided the opportunity for learners from different parts of the country and the world to access UP education. To enhance the sufficiency of these opportunities, the University adopted ODL as an approach to teaching and learning. As a mode of delivery, ODL enables learners regardless of their location to study at their own pace and place. The delivery of content, as well as the interaction between and among the teacher and the learners, are mediated through technology. Since the students are not required to be physically present in a classroom, the number of students UPOU can admit is not hampered by availability of classrooms

and other physical infrastructure. Availability is also measured in terms of sufficiency of teaching staff. UPOU currently has 36 full-time regular faculty members, 239 affiliate and adjunct faculty members, and 20 lecturers. From here, we can see that the University has relied on its network of part-time faculty members from other UP constituent universities, other educational institutions, and the professional/industry sectors. These part-time faculty members are oriented on the basic principles and practice of ODeL before they teach at UPOU. As previously discussed, availability should also be reflected in the range of courses or programs offered by an educational institution. UPOU currently offers 2 doctoral, 12 master’s, 11 diploma, 2 graduate certificate, and 3 undergraduate programs.

These degree offerings are in the areas of education, information and communication studies, and management and development studies. In addition to these formal programs, the university also offers 11 non-formal courses in the areas of entrepreneurship, environment and natural resources management, education, and health. Through UPOU’s formal academic programs, learners get advanced studies and training in a range of applied professions. Learners who want to acquire practical skills set or individuals who are not yet ready for a full-degree program or those who just want to continue learning and earn certificates and be familiarized with online learning can take any of its fee-based, short non-formal courses or any of its freely available massive open online courses (MOOCs). UPOU has also opened up learning opportunities through the production and distribution of open educational resources. For almost a decade now, UPOU has shared educational videos, e-books, and audio learning resources via an online repository called the UPOU Networks. Released through a Creative Commons license, these learning resources are for use and sharing or re-distribution of everyone. The resources are also promoted via social media for the awareness of the larger public. Providing entry points to the educational system to non-traditional learners is also a means of enhancing availability. In addition to expanding its learner base through the provision of formal courses, non-formal or professional continuing education, MOOCs, and OER, UPOU has also introduced alternative pathways to expand the learning opportunities to its formal academic programs. For example, UPOU instituted the Undergraduate Assessment Test (UgAT) to provide opportunities for other learners who have left the university to pursue tertiary education again. UgAT is one of the filtering mechanisms at UPOU to measure the intellect and competency of an undergraduate applicant who had failed to meet either the minimum number of units in college or general weighted average (GWA), or who neither attended nor finished secondary education in the formal school system but had passed a placement or accreditation and equivalency test such as the Alternative Learning System Accreditation and Equivalency Test and the Philippine Educational Placement Test (PEPT).

UPOU is also providing programs to offer multiple pathways for a more flexible learning experience through the institution of an independent learning track for the Diploma in Science Teaching (DST) program, and the institution of multiple entry and exit degrees. In the independent learning track, students are given the choice to complete their courses anytime within an academic year. In some programs with multiple entrances and exits, students can enter either through a diploma, a master’s program, or vice versa. These programs allow learners to exit to a lower degree if they opt to. This flexibility allows learners to choose a program that suits their needs at the present but also the space to make another choice once their circumstances also change. In this way, higher education becomes more responsive to the changing needs of contexts of learners. The sufficiency of infrastructure for learning is also a major concern in the concept of availability.

Since UPOU delivers its courses at a distance, and in particular through online learning, the University has set up technology infrastructure for learning as well as learner support. In terms of instruction, UPOU has put MyPortal, a learning management system powered by Moodle, where students can access their course, do learning activities, and interact with their teacher and co-learners. Student support services are delivered through Online Student Portal (OSP), which serves as the online gateway of UPOU’s academic operations through which students can register online, view their final grades, pay online, request for documents, view important announcements, and access the online course sites, e-library resources, online order system for learning materials, and student evaluation of teacher (Secreto & Pamulaklakin, 2013). Physical and digital libraries are also available for all students at UPOU. The Examination Unit of the Office of Student Affairs (OSA) administers the conduct of examinations through the university online examination system or through the testing centers located in different parts of the country and accredited examination venues (i.e.,Philippine consular offices) abroad. Inquiries about UPOU program offerings can be accessed through the UPOU Chatbot, known as IskOU-Iska.

2. Accessibility

Provision of opportunities is not enough since learners have different abilities and resources in accessing these opportunities. Accessibility focuses on reduction (if not removal) of barriers that hinder “interested and prepared” but “disadvantaged” individuals from accessing available opportunities. These barriers may include tuition, “competitive exams that disadvantage those with poor quality previous schooling, geographical location of institutions, the opportunity costs of spending years out of employment, as well as a range of other constraints relating to language, culture, and identity” (McCowan, 2016, p. 657). Accessibility is concerned with conditions that support all to access sufficient opportunities. There are several ways that can enhance accessibility in higher education. The most common way that HEIs use to address financial limitation of willing individuals is by offering scholarship grants and loans, such as the university loan system in England and the Prouni initiative and partial loans in Brazil (McCowan, 2016) as well as loan programs in Mexico and Chile (Altbach et al., 2009). While these initiatives address the financial concern of “interested” individuals, there are also technological barriers that hinder them from accessing higher education through ODeL, which is supposedly a way to bring education closer and accessible to everyone. McGill (2010), as cited in Willems and Bossu (2012), acknowledged that “not all learners have access to computers, or to the internet” and suggested the use of “alternative technologies,” which can be mobile learning applications (p. 191). Debattista (2018) emphasized the importance of providing clear instructions on how to access all elements of the online learning environment. Moreover, resources indicated to fulfill the learning outcomes should be open and accessible to all the learners without unwarranted technical, financial, or administrative barriers. OERs and MOOCs can be a good example of this (Debattista, 2018; Priyogi et al., 2017). The virtual learning environment should also be device-/platform-agnostic as much as possible, so that it would be accessible over different software platforms, browsers, and computing devices. Accessibility also pertains to openness of access to education for everyone

on a large scale. Pisutova (2012), as cited in Priyogi et al. (2017), categorized open services as open content, open courseware, open educational resources, and open teaching. Openness is concerned with the accessibility of information that students may need to know and consider in accessing services in higher education, including the defined functions of the online teacher and of the persons involved in the development of the program, the assessment criteria of the learning process, and the detailed criteria to be used to grade the students’ progress (Marciniak, 2018). As previously discussed, availability does not guarantee equity of access since learners are not alike in terms of resources, abilities, preparation, etc. To achieve accessibility, certain barriers to education must be addressed. Going back to the case of the UPOU, we have seen how the University has adapted ODL as a means to make its academic offerings available to more people. By using ODL as its means of instruction, UPOU’s education is made accessible to learners in different parts of the world, those who cannot study in conventional universities due to family, work, and other commitments, or those who are physically unable to do their studies in a brick and mortar campus. Studying at a distance also allows learners to save on costs associated with living in or travelling to and from a campus. In a developing country like the Philippines, economic inequality poses a challenge to accessibility to quality education. To address this barrier, the University has partnered with other organizations and agencies to secure scholarship grants to qualified students, in addition to the student loan program provided to students having financial hardships.

By using online resources, specifically OERs, to deliver content, the University was able to cut down the cost associated with producing and delivering printed learning materials. The University also acknowledges that the issue of digital divide is another hurdle to contend with, and so UPOU has also worked with private and government institutions in the provision of ICT equipment and connectivity in selected areas. As previously mentioned, the university has introduced an entrance examination (UgAT) for students who have not traditionally been able to enter UP for not meeting the usual eligibility requirements for admission or transfer to undergraduate programs. Passers of the UgAT are admitted to the Associate in Arts (AA) program. Graduates of the AA program can apply admission to any of the bachelor’s degrees in UPOU or any UP constituent university (subject to the latter’s admission procedures) and with most of their course credited towards the bachelor’s degree. In recognition that students come from different levels of preparation for university studies, UPOU has also offered free bridging courses in English and Mathematics to those who may need it. Before students are also admitted to the program, they are normally required to take a Distance Education (DE) Readiness Module to orient them to the nature of online earning and also familiarize them with the mechanics of navigating the virtual classroom. The University has also removed some of the usual admission requirements that tend to discriminate against certain types of learners. For instance, for most graduate programs, a bachelor’s degree in any field has become the minimum educational requirement for admission to allow for career shifters to be able to enter their chosen program. In graduate programs where the entrance examination used to be the sole or the major basis for evaluating students, the score for the written test has now become just one of the many criteria considered.

The maximum residency rule (or the maximum number of years given to the student to finish the course) has been practically doubled in the University in consideration of the fact that most of its learners are combining their studies with work and other commitments. The University has also set up a learning support system to address the administrative and learning needs of its students. Aside from the DE Readiness Module that applicants for admissions or newly admitted students need to take, the University has student support staff assigned to address the administrative inquiries of its students. The OSA conducts online and face-to-face orientations to newly admitted students to familiarize them with the university’s academic and program policies and procedures. Part of the orientation is the Grand Sunduan which is an event where incoming learners can meet current students and even alumni. Past students are also invited to share their experiences on being effective online learners. OSA’s Examination Unit administers mock examinations to familiarize students with the use of the Online Examination System before taking their actual online examinations. OSA also arranges the proctored sit-down examinations of students in any of UPOU Learning Hubs, Testing Center, or any accredited venue. Academic advising is provided by the Program Chairs and online psychosocial counseling to students is also accessible through OSA. Students can also email inquiries or talk to a student support staff based in the Faculty Offices or the Learning Hubs. Aside from its online repository of online publications, the Library can send out books to students via courier. At present, the University is also working on making its courses and programs accessible to the differently abled. Starting with redesigning the university website to meet Universal Accessibility requirements and initiating the mobile version of MyPortal, UPOU is now working on applying the same to its courses and learner support systems.

3. Horizontality

Horizontality refers to “the characteristic of even prestige and quality across the system” (McCowan, 2016, p. 657). Horizontality does not assume that all educational institutions need not be the same since there are benefits to having diversity in terms of program focus, ethos, research specializations, etc. It simply means that “this diversity should exist in the context of consistently high quality and recognition of diplomas in the broader society” (McCowan, 2016, p. 657). Horizontality does not preclude differentiation among universities in terms of identities and outcomes but warns against providing access to higher education on the basis of merit or ability to contribute, given that merit is often underpinned by socioeconomic privilege. Horizontality does not subscribe to the idea that elitist admission practices are justified if it would lead to the production of high-level knowledge workers needed by society. If higher education is indeed beneficial not only in economic terms but also in the development of the human potential, horizontality argues that higher education should be made accessible to those who really want it (McCowan, 2016).This concept is applicable in the case of UPOU which is part of the National University of the country and the highest-ranking Philippine university (CNN Philippines, 2020). When it was established twenty-five years ago, it was designed to make “UP quality” education within the reach of learners who cannot normally access it in its existing brick and mortar campuses. The idea was to make UP “more open” to more Filipinos. There was no intention to water down the quality of UP even as it makes its programs available to more people. While it has always been guided by the principles of ODL, UPOU was more focused on distance learning as a means of addressing the barriers of time and geography. As it evolved over the years, UPOU began to incorporate more openness values as it attempts to address other barriers to education like access to learning resources, different levels of academic preparation, exclusionary admission policies, rigid curricular structures, etc. As part of the UP System, UPOU has straddled the realm of a traditional university and that of an open university. It still abides by the same quality framework—Internal Academic Assessment and Development System (iAADS)—used by the UP System to evaluate the quality of its academic programs. It also subscribes to the UP vision of producing graduates who have (1) critical and independent thinking; (2) sense of humanity and justice (or the fundamental respect for others as human beings with intrinsic rights); (3) sense of being Filipino; (4) vocation for service, more specifically, for national service; (5) the value of personal integrity and intellectual honesty; (6) sense of professionalism or the rigor and standards applied to work in particular disciplines; and, (7) the value of enlightened spirituality that is not necessarily based on religion in rendering “considered judgments” (University of the Philippines Office of the Vice President for Academic Affairs [UP OVPAA], 2019).

As discussed above, in adopting ODL, UPOU was able to move away from the “competitive allocation of a fixed (and small) number of places” (McCowan, 2016, p. 651). Even as it opens up opportunities to more diverse learners, it has worked to maintain evenness of quality across the UP system. Since learning materials are the first point of study among distance learners, UPOU has established the Quality Circle, a multiple-expert review mechanism to ensure that course packages are not only relevant and up-to-date and pedagogically appropriate in the context of its distance learners. In its initial years, UPOU delivered its course content primarily through stand-alone modular books in print. As it fully moved to online learning by 2007, UPOU adopted a resource-based approach to course materials development. This approach is based on the principle of resource-based learning (RBL) which encourages the use of multiple learning resources in various formats to promote active learning. While traditional assessments (i.e., examinations) are still done in the university, there is also an emphasis on the use of alternative assessments (i.e., assignments, reports, papers, and projects) and online discussion forums, which promotes co-creation of knowledge. While the academic discourse among learners has been done mostly asynchronously, they are done not only to encourage the development of learners’ analytical and critical thinking skills but also promote openness to multiple perspectives (Garcia, 2020)—skills and values that have been traditionally associated with UP (Dalisay, 2018). Recently, there has also been a move to add thesis as a terminal requirement in all the university’s graduate programs, to make it more aligned with UP’s mission as a research university (UP Charter, 2008). While monthly face-to-face study sessions with students were replaced by online tutorials and discussions when the instruction became fully online, UPOU faculty members have tapped various social media and multimedia technologies to facilitate higher-order learning outcomes through collaborative learning and interactive and multimedia-based learning activities, whether these are done synchronously or asynchronously (UPOU, 2010). The road to greater horizontality is not easy. The evenness in quality across the system that horizontality advocates for cannot be achieved without putting in accessibility measures. To address economic barriers, UPOU, especially in its early years, actively sought the support of various agencies and individuals for the provision of scholarship grants to disadvantaged students. One such initiative was a scholarship program given to selected public school teachers in Quezon province, which also included the provision of digital literacy training, laptop computers, and internet gadgets to the scholars. Furthermore, the University also needed to beef up its financial assistance programs (i.e., low-interest student loans) for such students. There is also the issue of technology access. The Philippines’ internet connection is reported to be lagging behind its neighbors. Many rural areas in the country still do not have stable internet access. On the other hand, Filipinos are the world’s number one social media users in terms of time spent online.

There are 76 million active social media users and 72 million mobile social media users (Seavers, 2019). With over 2.3 Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) living abroad (Philippine Statistical Authority [PSA], 2020), Filipino families also had to rely on the internet to communicate with their loved ones. While the local internet infrastructure is undergoing further development (iGov Philippines, n.d.), Filipinos’ affinity for social media use also indicates that there is a system of technology-mediated communication practices that exist out there. The challenge lies now in how to translate these practices for educational purposes, so more people can be better prepared for an increasingly digital world. Developing competencies in online teaching and learning, as well as setting up web-based student support systems, takes some time. The fact that UPOU took a risk when it adopted a virtual learning environment in 2003 and offered fully online courses in 2007 shows the strategic importance of long-range planning and organizational learning. While economic and technological factors are usually the commonly cited barriers to access, other so-called “soft” issues also need attention. Digital literacy, for instance, varies across sectoral groups. To contribute to the task of preparing future learners, especially those from disadvantaged groups, UPOU has actively partnered with various organizations in the conduct of digital literacy seminars and workshops for thousands of public school teachers. Bridging courses, like those in College English and Mathematics, have also been offered in recognition that opening up the University doors to more diverse students means addressing their different levels of preparation for higher education. The University has also conducted several seminars on universal accessibility as it prepares to make its courses accessible to people of different abilities. Despite these efforts, there is still a lot of work to be done. More learners from marginalized groups need to be attracted. There is still a need to tackle other barriers like cultural issues (i.e., predominance of English in learning materials, the lack of Asian/South/Philippine/Indigenous perspectives in courses, gender issues, etc.). Decolonizing content (Lebeloane, 2017) is a huge concern in itself but is crucial if we are to make our academic offerings truly accessible and relevant to more people. Learning support programs for non-traditional learners also needs to be strengthened.

Worldwide, there is an increasing call for higher education institutions to include fairness and inclusion in their agenda (OECD, 2008; UNESCO, 1990). UNESCO identified ten elements that contribute to quality education which are under two levels—learner and education system levels (Pigozzi, 2006). These elements highlighted the importance of acknowledging the diversity of learners and considering their varying experiences, interests, language, and culture in developing curriculum and learning content as well as in implementing and managing processes across the education system.

In many universities around the world, however, student selectivity has been used as a proxy for quality. It still figures as one of the criteria for university rankings. This idea is based on the systems view of quality that the quality of outcomes (graduates) is dependent on the quality of processes (instruction, programs, and facilities), which in turn is influenced by the quality of inputs (college first-year entrants) (Tan & Decena, 2015). In some cases, participation of disadvantaged students in higher education is viewed as possibly resulting in “higher attrition rates, poor student performance and progression, and significant resourcing of academic support services” (Whiteford et al., 2013, p. 302). There is also this belief that disadvantaged or nontraditional students take longer to complete and would require more assistance from their teachers to the detriment of their high performing counterparts. Contrary to this traditionally held view, however, is a small but growing body of empirical work indicating that social inclusion measures do not lead to deterioration of academic standards (Brink, 2008; Griffin et al., 2010, as cited in Whiteford et al., 2013; Whitla et al., 2003). Among the initiatives instituted by universities that have been successful at diversifying their students include: outreach and transitional programs and alternative entry points for disadvantaged students entering higher education; provision of well-coordinated support services once they enrol; alternate entry opportunities for disadvantaged students; orientation to social inclusion and the access and equity agenda in the university operations (Whiteford et al., 2013).

Horizontality is concerned not only in promoting equity of access to higher education but also in ensuring quality in the education system. QA frameworks in conventional universities have generally focused on assessing teaching and research based on a set of performance indicators. On the other hand, QA frameworks in open universities have mainly focused on the institution’s processes in terms of its policies, management, resources, research, and program and course development. In most open universities, access is already given and so it does not figure much in their QA frameworks.

From the standpoint of horizontality, how should equity of access figure in quality frameworks of higher education in general and ODeL specifically? Opening up universities to a diverse set of learners requires introduction of accessibility measures to ensure that disadvantaged learners are able to actually take advantage of the learning opportunities made available to them and that they do not fall into the cracks of the system. From a QA systems perspective, this may require the inclusion of the following elements:

• Inputs: Diversity of Learners

• Throughput: Accessibility Programs (alternative entry points, learning support programs for non-traditional learners, universal accessibility, etc.)

• Outcomes: Diversity of graduates

As an ODeL institution, UPOU is in the midst of negotiating these multiple goals. In addition to reviewing the current university’s academic evaluation system to make it aligned with its openness mandate, it is looking for alternative means (i.e., learning analytics-based as opposed to performance indicators-based QA) to address learning problems in the online environment. UPOU’s evolving experience in developing and implementing quality management systems in ODeL can be of use not only to open learning institutions but also to conventional universities that are intent on adopting technology-based education or online learning as a means to creating more learning opportunities for students. As an open university that is part of a university system that is largely residential in nature and culture, UPOU straddles both the world of ODL and conventional higher education. Its experiences can, therefore, be a source of lessons for the rest of the higher education sector as well.

higher education: Tracking an academic revolution [Conference

session]. 2009 World Conference on Higher Education – The New

Dynamics of Higher Education and Research for Societal Change

and Development, Paris, France. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/

ark:/48223/pf0000183168

ASEAN University Network. (2015). Guide to AUN-QA assessment at

programme level version 3.0. http://www.aunsec.org/pdf/Guide%20

to%20AUN-QA%20Assessment%20at%20Programme%20Level%20

Version%203_2015.pdf

ASEAN University Network. (2016). Guide to AUN-QA assessment at

institutional level version 2.0. http://www.aunsec.org/pdf/Guide%20

to%20AUNQA%20Assessment%20at%20Institutional%20Level%20

Version2.0_Final_for_publishing_2016%20(1).pdf

Asian Association of Open Universities. (n.d.). Quality assurance framework.

http://aaou.upou.edu.ph/quality-assurance-framework/

Belawati, T., & Zuhairi, A. (2007). The practice of a quality assurance system

in open and distance learning: A case study at Universitas Terbuka

Indonesia (The Indonesia Open University). International Review of

Research in Open and Distance Learning, 8(1), 1–15. https://doi.

org/10.19173/irrodl.v8i1.340

Campos, D.F., dos Santos, G.S., & Castro, F.N. (2017). Variations in student

perceptions of service quality of higher education institutions in

Brazil.Quality Assurance in Education, 25(4), 394–414. https://doi.

org/10.1108/QAE-02-2016-0008

Chapman, B.F., & Henderson, R.G. (2010). E-Learning quality assurance: A

perspective of business teacher educators and distance learning

coordinators. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal, 52(1), 16–31. https://eric.

ed.gov/?id=EJ887220

Chien, C., & Huebler, F. (2018). Introduction. In UNESCO, Handbook on

measuring equity in education (pp. 11–15). UNESCO-UIS. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/handbook-measuring-

equity-education-2018-en.pdf

Chipere, N. (2017). A framework for developing sustainable e-learning

programmes. Open Learning, 32(1), 36–55. http://doi.org/10.1080/

02680513.2016.1270198

CNN Philippines. (2020, February 19). UP among world’s top universities

in emerging economies. CNN Philippines. https://cnnphilippines.

com/news/2020/2/19/Times-Higher-Education-UP-top-universities-emerging-economies-.html?fbclid=IwAR1g2_UwRlNrJuns6mdBZOzvP

M5tY0cXbhIWQQ9TMU7-LkeE4Qcmor1NvU0

Commission on Higher Education. (n.d.). Programs and projects. https://ched.

gov.ph/programs-and-projects/

Dalisay, J.Y., Jr. (2018, October 22). The freedom of intelligence. University of

the Philippines. https://www.up.edu.ph/the-freedom-of-intelligence/

Debattista, M. (2018). A comprehensive rubric for instructional design in

e-learning. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology,

35(2), 93–104.https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-09-2017-0092

Fallows, S., & Bhanot, R. (2005). Quality in ICT-based higher education: Some

introductory questions. In R. Bhanot & S. Fallows (Eds.), Quality

issues in ICT-based higher education (1st ed., pp. 1–6). https://www.

researchgate.net/publication/30067969_Quality_in_ICT-based_

higher_education_Some_introductory_questions

Garcia, P. (2020, January 5). Designing discussion forum [Video]. UPOUNetworks. https://networks.upou.edu.ph/26736/designing-discussion-forum-dr-primo-g-garcia/

Hazelkorn, E. (2013, May). Rankings and implications for quality

assurance in higher education [Paper presentation]. Exploring

Quality Assurance Through the Africa-EU Partnership Policy

Workshop EU-Africa Joint Strategy, Gabon, Africa. https://

arrow.dit.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.

com/&httpsredir=1&article=1057&context=cseroth

Integrated Government Philippines Program. (n.d.). DICT projects to serve citizens in the countryside. https://www.gov.ph/web/integrated-government-philippines-program/news/-/asset_publisher/CkCxB4U3kVLk/content/dict-projects-to-serve-citizens-in-the-countryside

Lalic, A.B. (2017, January 18). How quality of higher education should be

measured by university rankings? IEDC-Bled School of Management. https://www.iedc.si/docs/default-source/Publications/how-quality-

of-higher-education-should-be-measured-by-university-rankings.pdf?sfvrsn=0

Lebeloane, L. (2017). Decolonizing the school curriculum for equity and social

justice in South Africa. KOERS – Bulletin for Christian Scholarship,

82(3). https://doi.org/10.19108/KOERS.82.3.2333

Letseka, M., & Pitsoe, V. (2012). Access to higher education through open

distance learning (ODL): Reflections on the University of South Africa

(UNISA). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263469362_

Access_to_higher_education_through_Open_Distance_Learning_

ODL_reflections_on_the_University_of_South_Africa_UNISA

Lumanta, M.F., & Carascal, L.C. (Eds.). (2018). Assessment praxis in open and

distance e-learning: Thoughts and practices in UPOU. University of

the Philippines Open University.

Malik, S.K. (2015). Strategies for maintaining quality in distance higher

education. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 16(1), 238–

248. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1092842.pdf

Marciniak, R. (2018). Quality assurance for online higher education

programmes: Design and validation of an integrative assessment

model applicable to Spanish universities. International Review of

Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(2), 126–154. http://

www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/3443

McCowan, T. (2016). Three dimensions of equity of access to higher education.

Compare, 46(4), 645–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.201

5.1043237 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2008). Ten

steps to equity in education. https://www.oecd.org/education/

school/39989494.pdf

Peter, S., & Deimann, M. (2013). On the role of openness in education: A

historical reconstruction. Open Praxis, 5(1), 7–14. http://doi.

org/10.5944/openpraxis.5.1.23

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2020). Statistical tables on overseas

Filipino workers. https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/survey/labor-force/

sof-index#:~:text=at%202.3%20million.-,Total%20Number%20

of%20OFWs%20Estimated%20at%202.3%20Million%20

(Results%20from,2017%20Survey%20On%20Overseas%20

Filipinos)&text=April%2027%2C%202018-,The%20number%20

of%20Overseas%20Filipino%20Workers%20(OFWs)%20who%20

worked%20abroad,was%20estimated%20at%202.3%20million

Pigozzi, M.J. (2006). What is the ‘quality of education’? (A UNESCO perspective).

In K.N. Ross & I.J. Genevois (Eds.), Cross-national studies of the quality

of education: Planning their design and managing their impact (pp.

39–50). International Institute for Educational Planning. http://www.

ipz.uzh.ch/dam/jcr:00000000-2029-c978-0000-00002f5210b7/

25-book.pdf#page=34

Priyogi, B., Santoso, H.B., Berliyanto, & Hasibuan, Z.A. (2017). Analysis of open

education service quality with the descriptive-quantitative approach. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 16(3), 23–35.

Republic Act No. 7277: Magna Carta for Disabled Persons 1992 (Phi.). https://

www.ncda.gov.ph/disability-laws/republic-acts/republic-act-7277/

Republic Act No. 9500: The University of the Philippines Charter of 2008.

(2008). https://www.up.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/

RA_9500.pdf

Republic Act No. 10650: Open Distance Learning Act 2014. (2014). https://

www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2014/12/09/republic-act-no-10650/

Republic Act No. 10931: Universal Access to Quality Tertiary

Education Act 2017. (2014). https://ched.gov.ph/wp-content/

uploads/2018/01/20170803-RA-10931-RRD.pdf

Seavers, D. (2019, August 7). Social media statistics in the Philippines. Talkwalker. https://www.talkwalker.com/blog/social-media-statistics-philippines

Secreto, P.V., & Pamulaklakin, R.L. (2013, January). Learners’ satisfaction level

of the online student portal as a support system in ODeL environment

[Paper presentation]. International Conference on Open and Flexible

Education (ICOFE), Open University of Hongkong, Hongkong.

Tan, J.W., & Decena, R.A. (2015). Access-quality model in higher education.

NMSCST Research Journal, 3(1), 157–173. https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/321128961_Access-Quality_Model_in_Higher_

Education

United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable development goals: Quality education.

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/education/

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (n.d.).

Leading SDG 4 – Education 2030. https://en.unesco.org/themes/

education2030-sdg4

United Nations, Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (1990,

March 5-9). World declaration on education for all and framework for

actions to meet basic learning needs [Conference session]. World

Conference on Education for All Meeting Basic Learning Needs,

Jomtien, Thailand.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (1998).

World declaration on higher education for the twenty-first century:

Vision and action. http://www.unesco.org/education/educprog/

wche/declaration_eng.htm

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2005a).

Guidelines for inclusion: Ensuring access to education for all. UNESCO.

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000140224

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2005b).

Understanding education quality. In EFA Global Monitoring Report

2005 (pp. 27–37). http://www.unesco.org/education/gmr_download/

chapter1.pdf

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. (2000, June).

Defining quality in education [Paper presentation]. Meeting of The

International Working Group on Education, Florence, Italy. https://

www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/

resource-attachments/UNICEF_Defining_Quality_Education_2000.

PDF

University of the Philippines Office of the Vice President for Academic Affairs.

(2019). UP statement of the philosophy of education and graduate

attributes. University of the Philippines.

University of the Philippines Open University. (2010). Critical reflections on

teaching online. In P.G. Garcia and P.B. Arinto (Eds.), UPOU in the

digital age 2007–2009 (pp. 12–14). University of the Philippines

Open University.

Weller, M. (2014). The battle for open: How openness won and why it doesn’t feel like victory. Ubiquity Press. http://doi.org/10.5334/bam

Whiteford, G., Shah, M., & Nair, C.S. (2013). Equity and excellence are not

mutually exclusive: A discussion of academic standards in an era

of widening participation. Quality Assurance in Education, 21(3),

299–310. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263731905_

Equity_and_excellence_are_not_mutually_exclusive_A_discussion_

of_academic_standards_in_an_era_of_widening_participation

Willems, J., & Bossu, C. (2012). Equity considerations for open educational

resources in the glocalization of education. Distance Education, 33(2),

185–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012

Garcia, P. G., Almodiel, M. C., & Pisueña, M. V. (2020). Access, Equity, and Quality in Open and Distance e-Learning. In Quality Initiatives in an Open and Distance e-Learning Institution: Towards Excellence and Equity (pp. 23-52). Los Baños, Laguna: UP Open University.