Is it ethical or even logical for a teacher to grade herself or himself? How responsive is UP Open University education to the demands of the 21st century workplace? How relevant are our programs to the needs of future employers of our students? Is there a relation between online dishonesty and the way students are being evaluated? This chapter attempts to answer the foregoing questions through an analysis of the dominant assessment models adopted by UP Open University programs, which do not differ much from conventional assessment models of brick and mortar institutions. It traces superordinate and subordinate influential factors of the open and distance e-Learning (ODeL) problematique and argues that conventional assessment models contribute to the problems associated with ODeL pedagogy and delivery. It offers third party or industry-based assessment as more appropriate alternatives for ODeL.

This chapter presents observations, views, and opinions that do not necessarily apply to K-12 basic education. Neither do they pertain to the physical and natural sciences as well as courses with established disciplines and standards (languages, mathematics, etc.). These observations relate to terminal assessments (i.e., end of term assessment/evaluation) that decides whether a student or a candidate will be promoted to the next level, passes or fails. In contrast, non-terminal assessments are those designed to generate feedback (i.e., self-assessment questions). Let me make it clear at the onset that this chapter recognizes the importance of assessment as adjuncts to education and does not disparage the voluminous work done in its name. It is with this belief that the observations and conclusions, views, and opinions contained herein are being shared. That being said, let me begin with my basic argument on why assessment should not be relegated to the online teacher.

In the past decade, there has been a shift in my professional practice. I have been involved in a number of development undertakings for most of my professional life. With my participation in UP Open University administration since 2002, the engagements that I chose tended to be more specialized and focused on what we call short-term monitoring and evaluation (M&E) assignments. These are one-to-three-week assignments where one conducts an ex-ante, midterm, final or ex-post evaluation of a development project. As a rule, evaluations of this nature are not conducted by the project itself nor by the agency that sponsors it. And for good reason. A third party could objectively analyze, assess, or evaluate an undertaking. A third pair of eyes, so to speak (the first being the project implementer and the second being the project beneficiary) leads to independent results. Engaging someone to provide an objective assessment makes good project sense. Let me relate this to the teaching-learning situation where half of the equation is “us,” the teacher. The other half is “them,” the learners. Current assessment practices are actually evaluations of the performance of both learner and teacher. With the latter doing most of the evaluating in class, the teaching-learning situation does not benefit from a third party or a third pair of eyes. Since the score given to students is indicative of the performance of the teacher, would it be ethical or even logical for a teacher to grade herself or himself?

The second argument for external assessment deals with curricular responsiveness. The article by Medina (2016) declared the preference of today’s employers for graduates from Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP) over those coming from the University of the Philippines, Ateneo de Manila University, De La Salle University, or University of Santo Tomas University. The claim, backed up by hard data, came with the remark that unlike students from these top universities, PUP graduates “don’t usually display an attitude of self-entitlement.” Indeed, this pervasive sense of entitlement among millennials, in general, is a universal turn-off not limited to employers. However, this preference may also be attributed to the growing gap between academic priorities and industry expectations.

Figure 1. Screenshot of Cosmopolitan’s frontpage dated 16 March 2017

Is UP Open University education responsive to the demands of the current workplace? We would like to think so. The very basic skills that our students learn are those that are considered very critical in 21st century education, online learning for example. However, let us frame the question in this manner: How relevant are our programs to the needs of future employers of our students?

To highlight my point, I revert to my recent engagements in M & E, something that employers coming from international development agencies would expect a graduate of development communication to be proficient in, especially a graduate of a professional degree such as the Master of Development Communication. Unfortunately, our curriculum at the moment does not include this particular competency. In its place, we offer training in scientific research, not even policy research. Why is it not there? I suspect it is primarily because academics put the curriculum together. It was our predisposition to academic social science research instead of applied developmental research that shaped the courses that we teach.

Figure 2 is a screenshot shared with the FICS faculty in 2014, which eventually became the basis for a chapter in the book, Developing Successful Strategies for Global Policies and Cybertransperency in eLearning (IGI Academic Publishers, 2016).

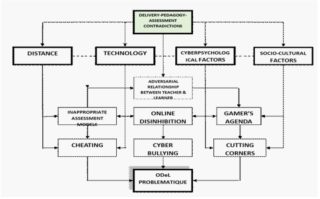

It is the front page of a paid service that offers to take online classes and exams for students leading to excellent grades. This is a classic case of classwork by proxy advertised openly on the Web. Through a grant from the UP Open University Office of the Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs (OVCAA) and the UP Office of the Vice President for Academic Affairs (OVPAA), a colleague and I looked into practices such as this. We were able to trace a problematique map where we clustered dysfunctional digital behaviors under three major categories: cheating, cyber-bullying, and cutting corners. Plagiarism, classwork-by-proxy, and employing ghost writers all fall under cheating. Cyberbullying covers behaviors associated with online disinhibitions. The third category of behaviors, cutting corners can best be understood with what we would like to call, The Gamer’s Agenda.

The Gamer’s Agenda refers to a tendency among some of our students to think of their online experience as a game between herself or himself and the instructor. She or he scores by outsmarting the instructor and overcoming the difficulties posed by cutting corners.

The problematique traces the causal links within this web of influential factors represented by boxes. The box on top embodies contradictions among our online delivery system, online-residential pedagogy and residential assessment practices. These contradictions lead to an antagonistic relationship between the teacher and the learner. Inappropriate assessment models form part of the problematique, which encourage cheating. Also, it influences the participants to assume a gamer’s attitude while online that, in turn, results in cutting corners.

Those of us who are familiar with gaming are aware that one of the primary objectives of the gamer is to look for ‘cheats’ or shortcuts. Once these shortcuts are discovered, one enjoys a bonus of accelerated in-game conquests and actually triumphs over an otherwise extremely difficult sub-routine. Some of our students look for these shortcuts, assuming that these are inadvertently contained within the course site.

Sadly, the problematique develops into a self-perpetuating adversarial system between the learner and teacher, the student and instructor. And it shows in the attitudes that some of us online teachers embrace. We become indifferent to students’ difficulties. We feel vindicated when we catch them in the act of cheating or cutting corners and acquire a sense of fulfillment when we design a solution to foil their shortcuts. The situation reminds me of a theory in the management sciences, MacGreggor’s Theory X – Theory Y. Theory X assumes that the employee, will cheat the employer the first opportunity that she or he gets while Theory Y assumes that the employee will follow the employer if she or he is given the chance to do so. These contrasting perspectives may also be applied to the teaching-learning situation. Should we assume Theory X to be true even among the best of our students? Alternatively, shouldn’t we assume that Theory Y is true even among the worst of our students? Fundamentally, was education meant for the student and the teacher to be on opposite sides of an online game competing against each other?

The grade point average (GPA) system has been adopted in our assessments. This in spite of comments from our master’s students that a difference of 0.25 in their final grade would send them to bouts of depression. ODeL programs, by definition, should be guided by open education philosophies instead of instructional procedures.

Applying conventional grading systems in a situation where the teacher and the learner are separated and have access to technologies is also problematic. Administering tests traditionally meant face-to-face interactions, but since we are separated from our students, it provides plenty of opportunities (and temptation) for hanky-panky. The prevalence of plagiarism is to the cut and paste affordances of technology. Hence, measures of cognitive gain may no longer be appropriate or accurate given this environment.

Instilling GPA primacy among online learners is inappropriate within the ODeL environment, particularly in higher education. This too gives rise to oppositional interactions between teachers and students, which in turn influence students to see the online classroom as an arena for a game. Engaging in this cat-and-mouse struggle has become the preoccupation of both students and teachers perennially sacrificing the primacy of learning and instruction.

To quote one of our honor students in her valedictory address: “Ngayong araw na ito ay patunay na nalusutan natin sila. (Today is proof that we have out-maneuvered them.) To our Professors, you were successful in giving us a hard time. But thank you, we were pressured to be better students. To the graduates, today is definitely a good time to ask for graduation gifts. This is our day. And today we celebrate that in spite of how much our Professors challenged us, we won over them! Congratulations, fellow survivors!”

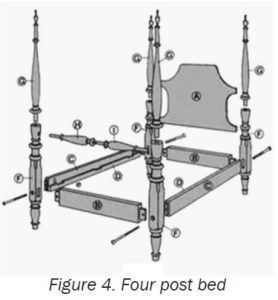

I used the four post bed as an analogy to our educational system that is composed of the following: a delivery subsystem, the curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment. In ODeL, we altered three subsystems, but retained the assessment subsystem of residential institutions. We changed our delivery system when we went online. We adapted our curriculum or content to courses and courseware that were more appropriate to online settings. We adjusted our pedagogies by introducing new tools such as Piazza, Basecamp, and others. But our assessment remained glued to the GPA model. We now have a situation wherein we changed the heights of the three posts but retained the height of one making the bed imbalanced.

We can address this imbalance by instituting policy changes. Firstly, if basic education requires traditional assessment models, then we should discourage ODeL in K-12. Higher education (HE), technical vocational education and training (TVET) and nonformal education (NFE) would profit more from ODeL provided these employ authentic assessments. Alternatively, formal assessments should be divorced from the instruction function. ODeL policy and practice should be made genuinely consistent with openness, independence, and constructivism. This may mean deviating from the traditional GPA. But can we offer a course without the teacher giving a numerical grade?

The fact of the matter is that grades did not always exist. No grades were required when the university system began in the sixth century. Four hundred years later, in the University of Bologna, a grading system was still unheard of. Much later in England, the first grade-based assessments were employed on cohort applications for the bar. The assessment was done by the courts and not by the universities. Grades were instituted just three centuries ago by European universities that fostered competitions among students for prizes and rank order.

Obviously, we cannot try these alternatives in our institution at this time by virtue of our policies. We cannot run a class without having a formal assessment afterwards. According to the UP Code, the University cannot offer a course without a final exam at the end of the term. We also have narrative assessments which are similar to the descriptions written for those who solicit recommendations for admission into graduate schools.

This is not numerical. There are also peer assessments that we conduct in many of our courses. These evaluations do not foster the so-called emphasis on numerical grades or GPAs. Then, there are third party assessments and authentic assessments.

Third party assessment is done neither by the teacher nor the learner or fellow-learners but by a third party organic within the university or affiliated with the industry. The methods could range from tests (scored through quantitative measures), demonstrations and simulations (in the technical or vocational sector, a learner is made to demonstrate how to caponize a chicken or castrate a pig or dismantle an engine) and portfolios.

Consider for instance a student taking Masters in Development Communication here at UP Open University which requires her or him to have academic residency for at least two and a half years or five semesters. If, for every course taken, there were no quizzes, homework, and exams. Instead a student would be asked to produce and write development communication knowledge products to be uploaded in her or his online portfolio. Every semester these portfolios would be populated with knowledge products, textual, or multimedia, learned during the course of the semester. When she or he completes the program, she or he would have an extensive portfolio to present to prospective employers and development agencies.

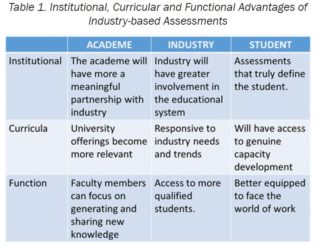

Third party assessments are done internally within the higher education institution or in another office independent from the faculty. It could also be done externally, conducted by a government body or an accredited institution as in the case of TVET in the Philippines. On the other hand, industry-based assessment is done by industry associations (such as chambers of commerce) or by employers themselves. Table 1 gives the institutional, curricular, and functional advantages of industry-based assessment for the academe, industry, and the learner:

Institutionally, the academe will have a more meaningful partnership with the industry, and the industry will have greater involvement in the educational system. As such, students will be subjected to assessments that truly define them instead of being defined by scores and grades. As far as curricula are concerned, university offerings will become more relevant. For industry, curricula will be more responsive to their needs and industry trends. And students will have access to genuine capacity development provided by updated and practical curricula. The Faculty, in turn, can focus on generating and sharing new knowledge. Industry will have access to more qualified students. In the end, students will be better equipped to face the world of work.

As champions of open education, we must take this learner-centered advocacy seriously and apply it to assessment. Otherwise, ODeL institutions exist as mere alternatives to residential education. Given the constraints, ODeL institutions will remain poor alternatives that employ technology to compensate for deficiencies based on standards dictated by traditional universities.

Flor, A.G. & Flor, B.G. (2016.) Dysfunctional Digital Demeanors: Tales from (and Policy Implications of) eLearning’s Dark Side. In Developing Successful Strategies for Global Policies and Cyber Transparency in E-Learning (Eby, G., Yuzer, T. V., & Atay, S., Eds). Hershey, PA: IGI Global Academic Publishers

Maligalig, J.P. (2012.) Employing games in development communication instruction. Professorial Chair Lecture. Los Baños: UPLB College of Development Communication

Medina, A. (2016, March). Employers now prefer PUP over UP, ADMU, DLSU, UST Grads, Cosmoplitan Philippines. URL

Ravasco, G. (2012.) Technology Aided Cheating in Open and Distance eLearning. Asian Journal of Distance Education. 10(2,) pp 71 to 77. ISSN 1347 9008.

Watson, G. and Sottile, J. (2010.) Cheating in the Digital Age: Do Students Cheat More in Online Courses. Retrieved on 8 April 2014 from http:// www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/spring131/watson131.html

Flor, A. G. (2018). Third Party and Industry-based Assessment Models: Remedies to e-Learning’s Dark Side. In M. F. Lumanta, & L. C. Carascal (Eds.), Assessment Praxis in Open and Distance e-Learning: Thoughts and Practices in UPOU (pp. 15-24). Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines: UP Open University