This cross-sectional study explored Connected Knowing and Separate Knowing in web-learning as an approach in evaluating the learning of online Diploma in International Health (DIH) students in IH 213 (Health Promotion for Equity and Sustainable Development) course at the UP Open University. Among the objectives of the study was to evaluate their learning in the course by determing their learning style — the use of Connected Knowing and/or Separate Knowing in web-learning. A total of 80 DIH students accomplished the questionnaire online via Google Forms from August 2014 to April 2015. Results point to the need for professors to encourage the use of integrated approach — both Separate Knowing (detached and critical) and Connected Knowing (attached and appreciative) in studyng their lessons and discussing subject matter with their professors and co-learners. To achieve this, the professor herself or himself must also use the approach and design appropriate assessment techniques that would not only gauge students’ learning but would also help them grow and be proficient in both modes of learning.

It is essential for teachers to know the ways by which students learn, and adjust their techniques in teaching and assessing the learning of students. Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule (1986) examined the epistemology, or “ways of knowing”, of a diverse group of women, with focus on identity and intellectual development across a broad range of contexts including, but not limited to, the formal educational system. While conceptually grounded originally in the work of William G. Perry (1970) in cognitive (or intellectual) development and of Carol Gilligan (1982) in moral or personal development in women, the authors discovered that existing developmental theories at that time did not address some issues and experiences that were common and significant in the lives and cognitive development of women (Love & Guthrie, 1999). In this study, the epistemology concept of Connected and Separate Knowing is not only confined to addressing women’s learning but also applied to men’s learning as there are very limited studies in the area. Specifically, the study sought to:

- determine the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents;

- evaluate the learning of respondents using connected and separate knowing; and .

- correlate the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents to their learnings.

Clinchy (1989) explains that the heart of Separate Knowing detachment. Furthermore, separate knowers are aloof from the object being analyzed. Separate knowers take an impersonal stance; they follow certain rules or procedures to ensure that judgment is unbiased. In contrast, connected knowers easily recognize disagreement but do not deal with disagreement by arguing. They are not dispassionate, unbiased observers. The heart of Connected Knowing is imaginative attachment. Connected knowers are uncritical. Generally, women are connected knowers while men are separate knowers.

Separate and Connected Knowing are classified as procedural knowledge. Procedural knowledge reflects recognition that multiple sources of knowledge exist, and that procedures are necessary for evaluating the relative merit of these sources. Procedural knowers focus on methods and techniques for evaluating the accuracy of external truth and the relative worth of authority. The transition to procedural knowledge was experienced by many women in the study, initially, as a regression or crisis of confidence, as the inner voice of subjective knowing became critical both of external authorities and internal subjective knowledge (Love & Guthrie 1999). However, what followed was the recognition that insights and information outside of personal experience could have a bearing on knowledge. Procedural knowers sought to understand authorities, focusing on reasoned reflection rather than absolutism, (Love & Guthrie, 1999) and evaluate information that could be interpreted in multiple ways through the use of context-specific procedures (West, 2004). Belenky, and colleagues (1986) describe two alternative modes of procedural knowledge: Separate Knowing and Connected Knowing. Separate knowers tend to be adversarial and focused on critical analysis that excludes personal feelings and beliefs. Academic environments often favor this form of procedural knowledge. Connected knowers, on the other hand, seek to understand others’ ideas and points of view, emphasizing the relevance of context in the development of knowledge and the fundamental value of experience. Most procedural knowers in the study were economically privileged, Caucasian, young college students or graduates.

Marrs and Benton (2009) studied the relationship between Separate and Connected Knowing and approaches to learning. In their study, they found out that connected and separate ways of knowing were related to deep and achieving approaches to learning. Two hundred forty-one (72 men and 169 women) white or caucasian and Mexican-American community college students in the Southwestern and Midwestern United States completed the Attitudes Towards Thinking and Learning Survey (ATTLS) and the Shortened Study Process Questionnaire (SSPQ). No significant differences in Separate Knowing and Connected Knowing were found between White and Mexican-American students. However, men scored higher than women on Separate Knowing and lower on Connected Knowing. In addition, both Connected Knowing and Separate Knowing were significantly related to a deep approach to learning while only CK was significantly related to achieving approach.

Relationship of Connected Knowing. and Separate Knowing to the learning styles of Kolb, formal reasoning, and intelligence was studied by Knight and colleagues (1997). The study which was composed of three separate studies revealed the following: study 1 (126 females, 117 males) found that males who were more connected were more likely to describe their style as emphasizing feeling rather than thinking (i.e., scored higher on Concrete Experience). Study 2 (59 females, 39 males) and study 3 (56 females, 58 males) found no relationship between Connected or Separate Knowing and formal reasoning and vocabulary or abstract thinking ability, respectively.

A study by Enns (2012) on Integrating Separate and Connected Knowing: The Experiential Learning Model explains that there are differences between Separate and Connected Knowing as previously explained by Belenky, and colleagues (1986). It also suggests that the Experiential Learning Model (Kolb, 1981, 1984) is a useful framework for integrating traditional, separate knowing, and connected, collaborative learning. The strengths of the model and a list of activities and examples associated with various learning positions were also identified.

Eighty (80) Diploma in International Health (DIH) students who served as respondents of the study were selected through cluster sampling. To collect data from the respondents, an online survey via Google Forms was carried out from August 2014 to April 2015. The questionnaires used for Connected and Separate Knowing were tested for validity and reliability resulting in Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8. Analysis of data was done using SPSS version 20. Mean and frequency were computed and relationships of the variables were determined using Spearman’s rank correlation.

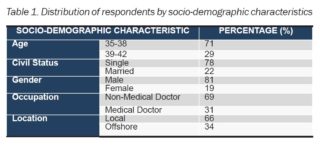

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic profile of the respondents and their percentage distribution. Seventy-one percent (71%) of the respondents were between 35-38 years old, and 29% were between 39-42 years old. 78% were single while 22% were married. There were more male respondents (81%) and more who were non-medical doctors (69%). Respondents were mostly pharmacists, nurses, or therapists. Lastly, 66% of them are based in the Philippines (local).

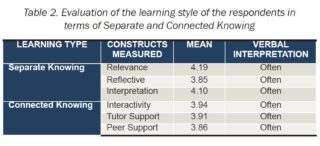

Evaluation of the Learning Style of the respondents in terms of Separate and Connected Knowing is shown in Table 2. Constructs measured in this study were relevance, reflective, and interpretation for Separate Knowing; and interactivity, tutor support, and peer support for Connected Knowing.

Results of the study revealed that students are often either separate and/or connected knowers. It can be implied from the results that more women use Connected Knowing while more men use Separate Knowing in online learning. Studies revealed that men are more comfortable than women with the adversarial style. Some men’s responses to questions about Connected Knowing reflect an ambivalence similar to the women’s attitudes toward argument. They ought to try harder to enter the other person’s perspective, but it is difficult and uncomfortable for them so they do not do it much (Clinchy, 1989).

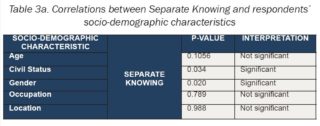

Table 3a shows the correlations between Separate Knowing and socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. Study reveals that among the socio-demographic characteristics, civil status and gender have significant correlations to being a separate knower. In terms of gender, the finding is similar to other studies which revealed that males are more of a separate knower while females are more of a connected knower Clinchy, 1989; Marrs & enton, 2009). Separate Knowing often takes the form of an adversarial proceeding. The separate knower’s primary mode of discourse is the argument. Separate knowers think of contrasting position and then argue it. In a class discussion, however, female students often refuse to argue with their teacher or classmates (Clinchy, 1989). A possible reason for this is that women have been taught since early childhood to speak in “small, soft voices” (Rich, 2012.). Rich (2013.) says women are taught about unfemininity of assertiveness. They are uneasy with the prospect of having to defend their opinions against each other. In terms of civil status, it can be implied from the result that single students can be more of a separate knower than the married ones since their limited life experience can lead to their being argumentative rather than being more understanding and empathic (Knight et al, 2000).

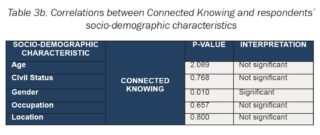

Table 3b shows the correlations between Connected Knowing and socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The study reveals that among the socio-demographic characteristics, only gender has significant correlations to being a connected knower. According to studies, women tend toward Connected Knowing, while men tend toward Separate Knowing (Clinchy, 1989; Marrs & Benton, 2009). A connected knower believes that in order to understand what a person is saying, one must adopt the person’s own terms and refrain from judgment. Women could recognize disagreement, but they do not deal with disagreement by arguing separate knower’s mode of discourse. When a woman disagrees with someone, she does not start arguing in her head, instead she tries to imagine herself into the person’s situation; she allies herself with the other person’s position even when they disagree with it. Instead of looking for what is wrong with the other person’s idea, women usually look for why it makes sense, how it might be right. While the voice of Separate Knowing is argument, the voice of Connected Knowing is narration (Cinchy, 1989).

Results revealed that the two ways of knowing are gender-related with more men than women showing a propensity for Separate Knowing and more women than men showing a propensity for Connected Knowing.

This goes to show that the students in the course, both men and women, must be encouraged to use the integrated approach—both Separate Knowing (detached and critical) and Connected Knowing (attached and appreciative). According to Clinchy (1989), this integral approach helps students develop systematic, deliberate procedures for understanding and evaluating ideas, and developing new ones. It makes them think and creates a learning situation that is more meaningful to them. Teachers would play an important role in helping their students develop this flexible way of knowing that is both connected end at separate.

According to studies, to help students achieve this learning approach, teachers or professors must also use an integrated approach — they should first be more liberal in terms of student’s ideas, rather than be excoriating. Teachers must first make connections with their experiences (e.g., their own failures) and the students’ efforts. Once the teacher had established a connection, the student could tolerate or even welcome the teacher’s criticism. Criticism will then become collaborative rather than condescending. This approach would help students adopt both Connected and Separate Knowing in studying their lessons and discussing subject matter with their professors and co-learners.

Considering men’s inclination toward separate knowing and women toward connected knowing, the professor of the course could also design appropriate assessment techniques which will not only gauge students’ learning, but would also help them grow and be proficient in both modes of learning–they will be critical and at the same time understanding or emphatic. Assessment tools such as online discussion forums and debates, among others, can be used to encourage discussion among students regarding the topics in the course. The discussion in a form of conversation and exchange of ideas or debates will serve as a perfect platform for students to freely narrate or argue their ideas and positions and exercise their use of both connected and separate ways of knowing.

Both teachers and students must value Connected Knowing, as well as critical thinking. Separate Knowing is of great importance. It allows people to criticize their own and other person’s thinking. On the other hand, Connected Knowing allows people to understand first the context of the knowledge source before thinking critically or evaluating the statement. Separate Knowing and Connected Knowing are both powerful ways of knowing.

Belenky, M.F., Clinchy, B.M., Goldberger, N.R., & Tarule, J.M. (1986). Women’s ways of knowing: The development of self, voice, and mind. Retrieved from https://cjsae.library.dal.ca/index.php/cjsae/article/viewFile/2341/2052

Clinchy, B.M. (1989). On critical thinking and connected knowing: Introduction to service learning tool. Liberal Education, 75: 14-19. Retrieved from http://capstone.unst.pdx.edu/sites/default/files/Critical%20Thinking%20Article_0.pdf

Enns, C. (1993). Integrating Separate and Connected Knowing: The Experiential Learning Model. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s15328023top2001_2

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Knight, K.H., Elfenbein, M.H., & Capozzi, L. (2000). Relationship of connected and separate knowing to parental style and birth order. Sex Roles, 43(3-4). Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1007080914728

Knight, K.H., Elfenbein, M.H. & Martin, M.B. (1997). Relationship of connected and separate knowing to the learning styles of kolb, formal reasoning, and intelligence. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1025605523940

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.ph/books?hl=en&lr=&id=jpbeBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&ots=Vn3ToR1USi&sig=jnkBVtCrdVLDcKF4Ukveh1j1Pqc&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Love, P.G. & Guthrie, V.L. (1999). Women’s Ways of Knowing. New Directions for Student Services. 1999: 17–27. doi:10.1002/ss.8802

Marrs, H. & Benton, S.L. (2009). Relationships between separate and connected knowing and approaches to learning. Sex Roles, 60 (1-2). Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11199-008-9510-7

Perry, W. (1970). Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED424494

Rich, A. (2012). Taking Women Students Seriously. Retrieved from http://www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/c/a/caw43/behrendwriting/Rich_women_students.pdf

West, E. (2004). Perry’s legacy: Models of Epistemological Development Journal of Adult Development. 11(2): 61–70

Oruga, M. D. & Bagos, J. R. Saludadez, J. A. (2018). Connected and Separate Knowing as an Assessment Framework in Evaluating the Online Learning of Diploma in International Health Students . In M. F. Lumanta, & L. C. Carascal (Eds.), Assessment Praxis in Open and Distance e-Learning: Thoughts and Practices in UPOU (pp. 77-85). Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines: UP Open University