Assessment is an important measure of learners’ construction of knowledge as contextualized by personal experiences and the environment. Digital assessments can be incorporated in the learning modules, happen in real time using various modes, enhance test items with embedded multimedia materials, be accessed anytime and anywhere with specific restrictions, and garner immediate or real-time feedback. Moreover, statistics generated from quizzes implemented within MyPortal provide student performance data that can serve as points for reflection and correction. This chapter aims to analyze current practice in online assessment using MyPortal, UP Open University’s learning management system. These statistics in MyPortal are divided into two sections: the quiz information and the quiz structure. These are the important quiz information statistics: average and median grade, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, coefficient of internal consistency, error ratio, and standard error. Quiz structure statistics pertain to statistics on each test item such as facility index, standard deviation, random guess score, intended weight, effective weight, discrimination index, and discrimination efficiency. The statistics provided for each test item can contribute to the overall improvement and effectiveness of the online assessment considering that the quiz statistics are available in real time. These data must be recognized as important inputs especially if the assessment contributes to measuring learners’ ability and skills. These are important features of a digital assessment that should be harnessed for quality assurance.

Technology-assisted learning allows learners and teachers to navigate and choose relevant topics related to the course. The constructivist approach to learning recognizes that learners do not acquire knowledge, but rather construct it. It is knowledge that is contextualized which means it is based on their personal experiences and continuous construction of hypotheses about their environment. Therefore, the constructivist approach to learning can be applied in the construction of online assessments. This forms part of reflective learning, a process where instructors look back on their teaching style; its effect on their students; and how their practice can be improved for better learning outcomes. This chapter aims to analyze current practice in online assessment using MyPortal, UP Open University’s learning platform that uses the MOODLE learning management system (LMS). It begins with an overview of assessment, then describes online assessment using quizzes in MyPortal, explains the models of reflection in online assessments, and gives in-depth insights into constructivist reflections on assessment using online quizzes. The availability of quiz statistics in MyPortal provides an opportunity for feedback assessment and continuing improvement of test items.

Overview of Assessment

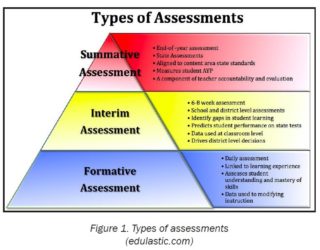

Generally, there are three types of assessment: assessment for learning (formative), assessment as learning (interim), and assessment of learning (summative) (Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education, 2006). There are various methods to provide diagnostic feedback to determine end-of-course achievement. They have a more narrowly defined focus on specific knowledge or skills and are designed to give an analysis of a student’s specific strengths and weaknesses, suggest causes for their difficulties, and offer recommendations regarding instructional needs and available resources. Figure 1 shows some examples of these types.

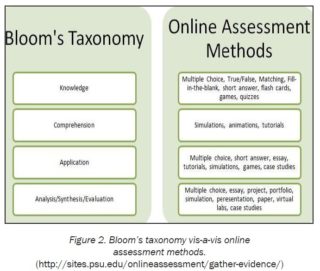

When online assessment is used, there is a foundational need for extensive stakeholder inquiry, understanding, professional growth, and cost analysis of information technology (IT), as identified in research (Howell & Hricko, 2006). Assessment is no longer limited to being just a tool for measuring a student’s knowledge of a course content. In addition, assessment is now also seen as essential in the wider scope of the learning process. These new methods make it possible to assess student performance before, during, and after a course is conducted. Figure 2 shows how Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning is used as a guide in choosing the appropriate online assessment method. It is arranged according to the level of difficulty – from simple knowledge acquisition, to comprehension, to application, and to complex analysis, synthesis, or evaluation.

Another key feature of effective online assessment designs is its need to use multiple measures through time. Doing a wide range of assessment methods gives students a chance to be evaluated holistically. It decreases the probability of penalizing students who happen to be weak in responding to just one or two teacher-preferred assessment forms. Technology in online assessment also offers greater quality than (F2F) assessments. Figure 3 highlights the benefits of online assessment: it is embedded in learning (timing), is universally designed (accessibility), is adaptive (pathways), is in real time (feedback), and enhanced (item types).

Online Assessment using Quizzes in MOODLE (MyPortal)

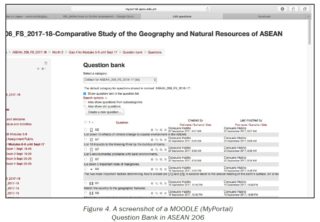

MOODLE provides a wide range of options for designing, constructing, and implementing online assessment. This section focuses on the use of quizzes in MOODLE. Quizzes are effective ways of formative and summative assessments. In MOODLE, test items for the course can be stored in a question bank (Figure 4). This can easily be accessed by the teacher in creating quizzes for specific lessons or modules.

New questions can be easily formulated from a drop-down list of examination types. These can be in the form of drag and drop onto image, essay, matching type, multiple choice, select missing words, short answer, true or false, and other types (Figure 5).

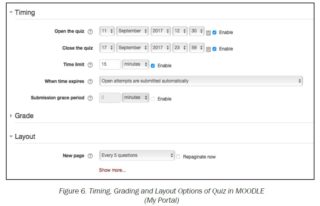

MyPortal affords the teacher the flexibility to set various options for the administration of the quiz. For instance, the date and time when the quiz is opened and closed, the total grade and number of attempts allowed, layout of the quiz, and question behaviour of the quiz can be modified according to the requirements of the teacher (Figure 6). However, the teacher must prepare the test items in advance and store them in the question bank. Test items can then be added to the quiz bank as needed.

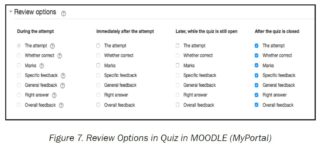

Another key feature of the MyPortal is the opportunity for students to receive immediate feedback after a quiz or assessment is completed. As the test question is being constructed, the answers to the test items are also provided by the teacher. Hence, the students get immediate feedback on their performance. Learners can also get feedback from objective type questions with choices ranging from during the attempt, immediately after the attempt, later when the quiz is still open, and after the quiz is closed (Figure 7).

Aside from objective type test items, essay questions can be formulated with the same options as objective test questions. Response options of students can range from the type of response format, whether students are required to enter text or text input is optional, input box size (5-40 lines), to whether attachments are allowed or required. However, based on experience, one hour and a half is the maximum time limit for an essay type of examination. Technical difficulties have occurred when an essay type of examination is set beyond one and a half hours, as this can cause the computer to go on sleep mode or being logged out from the course site. If only one attempt is allowed, then the student is barred from re-opening the quiz.

Models of Reflection in Online Assessment

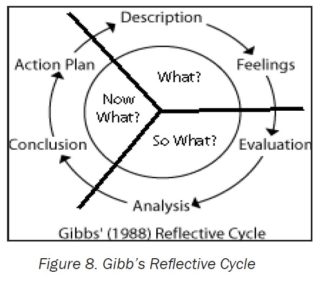

Online assessments like MOODLE (MyPortal) is still fairly new as it only started in 2002. Due to the novelty and newly-developed online assessment options, it is important to pause and reflect on their advantages, disadvantages, and future possibilities. “Reflection involves taking our experiences as a starting-point for learning. By thinking about them in a purposeful way—using reflective processes— we can come to understand them differently and take action as a result” (Jasper, 2003). The Reflective Cycle proposed by Gibbs (1988) is a never-ending process where theory and practice constantly interact with each other (Bulman & Schultz, 2013). It evokes autonomous reflexes to challenge suppositions, explore novel approaches and ideas, link practice with theory, and utilize critical and analytical thinking skills. When applied to reflections in online assessments, the Reflective Cycle encourages systematic thinking about the phases of online learning. It also allows for multiple perspectives on a given feature of online modes, thereby providing equilibrium and accurate judgment. The key questions it poses – “What?”, “So What?”, and “Now What?”—offer an opportunity for the teacher for reflection, analysis, and improved action (i.e., better assessment questions for students).

Applying Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle, the constructivist nature of online quizzes is shared from a practitioner’s point of view. In F2F modes of instruction typical in traditional university settings, formative and summative assessments are a major part of the requirements for a student to pass the course. In large classes consisting of about 80-100 students, it is very challenging for a teacher to mark essay questions or even to manually check a 100-point objective type of examination of all the students in the class. Thus, objective types of questions are more commonly used than essay questions due to the relative ease in marking. In practice, constructing and implementing exams for F2F classes are rarely evaluated on their appropriateness or relevance nor assessed in terms of difficulty and their use to differentiate strong from weak learners. Their usefulness is often considered achieved once the examination is marked and recorded. On the other hand, statistics generated from quizzes implemented within MyPortal provides student performance data that can serve as points for reflection and correction. Did the quiz achieve its purpose? Is the result of the quiz due to differences in ability of the students or is it due to chance effects? Did the grades from the quizzes indicate the true abilities of the learners? Quiz statistics generated by MyPortal offer a wealth of information that can be used and analyzed by teachers. These statistical data in MyPortal are divided into two sections: the quiz information and the quiz structure. The following are part of the list of important quiz statistics report: average and median grade, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, coefficient of internal consistency, error ratio, and standard error. The quiz information statistics recommends ideal standards. For example, kurtosis, which is measure of the flatness of the distribution of scores, should be in the range of 0-1. A value higher than 1 means that the quiz cannot distinguish poor from excellent students. A coefficient of internal consistency (CIC) value of more than 75% and an Error Ratio (ER) of less than 50% would indicate that on the whole, the quiz can distinguish poor from excellent students and is a good measure of their abilities. To improve the quiz overall, the teacher must look at the quiz structure statistics and perform the necessary correction. Statistics for quiz structure pertain to statistics on each test item such as facility index, standard deviation, random guess score, intended weight, effective weight, discrimination index, and discrimination efficiency. Thus, improving each test question can redound to the quality of the quiz as a whole. There are two important statistics for each test item. These are the facility index and the discrimination index. The Facility index (F) shows the mean score on each test item. If the facility index score ranges from 35-64%, the test item is about right or suitable for the average student. If F is more than 80%, the question is easy and if it is less than 20%, the question is difficult. F scores are indicative of the overall difficulty of each test item in the quiz. Given this F score, the test item can be changed or modified in order for it to be just right, and not too easy nor too difficult to answer. The other important measure of a test item is the discrimination index (DI). DI is defined as “the correlation between the weighted scores on the question and those on the rest of the test”. It can distinguish weak from proficient students. This analysis helps teachers to identify poorly-written questions or items and replace these with better-crafted questions.

In applying the Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle, the “What?” recognizes the existence and usefulness of online assessment in the form of quizzes in MyPortal. Assessment is an important measure of a learners’ construction of knowledge as contextualized by personal experiences and the environment.

The “So What?” presents a reflection on the overall quality of the online quiz in MyPortal in the form of quiz statistics. Data as revealed in the quiz statistics can now be used as part of a feedback loop to improve the quality of the quiz and likewise enhance the learning process. This feature is a big advantage over the pen-and-paper type of examination as practiced in F2F instruction typical of traditional universities.

The “Now What?,” online quizzes and the quiz statistics can form part of big data, and its usefulness in the analysis improvement of learning cannot be over emphasized. While quiz statistics may vary from one student cohort to the next, the statistics provided for each test item can contribute to the overall improvement and effectiveness of the online assessment. These data must be recognized as important inputs especially if the assessment contributes and measures learners’ abilities and skills.

Library/E_Books/Files/LibraryFile_151614_52.pdf Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. London: Further Education Unit (FEU).

Howell, S. & Hricko, M. (2006). Online assessment and measurement: case studies from higher education, K-12 and corporate. Hershey: Information Science Publishing.

Jasper, M. (2003). Beginning reflective practice. Nelson Thornes, Cheltenham. In Pearson, 2012). HCAs: Developing Skills in

Reflecting Writing. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants, 06 (03), 140-142.

Johns, C. (2000). Becoming a reflective practitioner: A reflective and holistic approach to clinical nursing, Practice Development, and Clinical Supervision. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Mehrotra, C., Hollister, C.D. & McGahey, L. (2001). Distance learning: principles for effective design, delivery, and evaluation. California: Sage Publications.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D. & Jasper, M. (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: A user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Walvoord, B. & Anderson, V.J. (1998). Effective grading: A tool for learning and assessment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education (WNCPCE). (2006). Rethinking classroom assessment with purpose in mind : Assessment for learning, assessment as learning, assessment of learning. Retrieved from http://www.wncp.ca/media/40539/rethink.pdf

Habito, C. dL. and Ealdama, S. J. G. (2018). Constructivist Reflections on Online Assessment. In M. F. Lumanta, & L. C. Carascal (Eds.), Assessment Praxis in Open and Distance e-Learning: Thoughts and Practices in UPOU (pp. 113-125). Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines: UP Open University