In this culminating chapter, it is suggested that quality considerations in every aspect of an assessment system in an open and distance e-Learning (ODeL) institution be incorporated in a multi-level, multi-function assessment framework. Levels of assessment are often discussed as assessment at course level, assessment at programme level, and assessment at institution level. Assessment at each level serves various and distinct purposes often referred to as, but not limited to, assessment of learning, assessment as learning, and assessment for learning.

Quality assessment is a process, engaged in by an institution, of evaluating its activities with the end in view of continuous improvement. In higher education, assessment, as concept and practice, may be viewed from a multi-level and multi-functional perspective to include assessment of learners within the course, assessment of programme and its alignment with mission of the institution, and assessment at the institution level as it addresses the needs of its various stakeholders. In this chapter, the authors attempt to identify dimensions that may lead to the development of a quality assessment system in the context of ODeL.

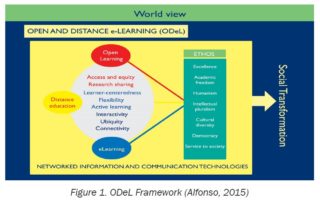

Assessment in its various forms has traditionally been discussed in the context of classroom-based education. More recently, however, with the introduction of open and distance e-Learning (ODeL), greater focus has been directed at quality considerations of an assessment system brought about by the unique circumstances of openness, distance, and technological advances. Variously referred to as distance education, open learning, distributed learning, flexible learning, and e-Learning (Alfonso & Garcia, 2015; Keegan, 1980), this teaching and learning approach capitalizes on independence of learners and increased flexibility in teaching methodologies necessitating greater openness in assessment at various levels. While in the past, quality assessment was based on a set of “fixed criteria” applied to the entire educational system, there is greater recognition now for a more adaptable set of “flexible criteria” (Reisberg, 2010).

In ODeL, the issues related to quality assessment are usually addressed in terms of technological innovations that impact on the teaching and learning process. The affordances of open learning, distance education and e-learning combined in the ODeL framework (Figure 1) include: “access and equity, resource sharing, learner-centeredness, flexibility, active learning, interactivity, ubiquity, and connectivity” (Alfonso, 2015). It becomes imperative, therefore, that in a quality assessment framework these are taken into consideration.

Levels of assessment often refer to the course, programme, and institutional levels. Miller and Leskes (2005) conceptualized levels of assessment from student to institution resulting in five levels of assessment. The first three of these refer to student and course level assessment where summative and formative assessment are employed. The authors discussed assessing student learning within courses, assessing student learning across courses, and assessing courses.

Evidence–based practice in teaching and learning engages various assessment information to monitor and/or assess student achievement and effectiveness of teaching, instructional programmes, or even the entire institution. These assessments provide guidance for possible adjustments in future instructional decisions, can be categorized into multiple types and levels, and can be considered in the University’s comprehensive assessment system. Currently, data-driven decision making as an ongoing process of analyzing and evaluating data informs educational decisions related to planning and instructional strategies at various levels. However, institutions would also use information that are not directly linked to student learning (e.g., teaching load, facilities, external collaboration) and include them in a comprehensive analysis of the academic environment, particularly at the programme and institutional levels.

In assessing student learning within courses, formative assessment is utilized in determining the students’ individual learning while summative assessment is used to identify how well they are meeting the goals of the course (Rahman & Ramos, 2003). Data gathered are usually sequential, since evidence is collected during and at the end of the course to monitor progress, thereby summing up a semester of learning. Evidence of student learning can be used for feedback to the course instructor’s ability to communicate with and motivate her or his students. The instructors’ duty also extends to assessing the quality of their teaching and evaluating the effectiveness of the pedagogical theories that they utilize (Rahman & Ramos, 2003). Although grades are used to evaluate students’ work, these only represent average estimates of the overall quality and provide negligible information about students’ strengths, weaknesses, or ways to improve. Analytical assessment, which can be structured through different tools such as using detailed rubric and written audio or video feedback, can reveal the exact concepts a student finds challenging. In ODeL, software systems (e.g., Learning Management Systems) are often used to support flexible learning and to perform a variety of functions such as designing assessment tools, marking rubrics, assessment feedback, and timetable of course activities, among others.

In assessing student learning across courses, summative and formative assessments would address how well students are learning during the progression of a particular programme or over the years of offering at the college or faculty. Evidence is sourced from the embedded work in individual course, student e-portfolios that assemble student work in a number of courses, projects, or even relevant external exams such as a licensure exam. Given the requisite formats and data, students may be able to collect the progress of their own learning across courses (Miller & Leskes, 2005). Assessment results are useful as summative or formative feedback for students to understand their progress over time. Likewise, these are also used as feedback to programme faculty on how well the students are meeting the goals and expected outcomes.

In assessing courses, data gathered from course assessments could be seen as formative feedback for instructors to make adjustments in their teaching, or summative feedback to help the instructor or the committee in charge of the course to make informed planning strategies (Rahman & Ramos, 2003). Instructors and committees are expected to set expectations, establish common standards for multi-section courses, understand how the course fits into a cohesive learning continuum, and use the evidence to improve teaching in the context of ODeL environment, including course design.

Programme level assessment is defined as “the systematic and ongoing method of gathering, analyzing, and using information from various sources about a programme and measuring programme outcomes in order to improve student learning as it aligns with the institution’s mission and goals” (University of Central Florida, 2008). Assessment at this level intends to focus on the learning, growth, and development of the students not as individuals, but rather, as a group. Similarly, programme level assessment looks into whether the programme fulfills its aim for the curriculum by providing an understanding of what the graduates know, what they can do with this knowledge, and what they value as a result of this knowledge.

In an ODeL context, a number of factors (e.g., selection and/or production of assessment instruments, conditions for assessment, supervising and authenticating, and managing procedures for possible revision and re-assessment) should be considered when doing programme level assessment. Particularly useful and important is the end point data as a summative gauge to determine how well the programme achieves its goals and objectives. Evidence of student learning from multiple sources (e.g., at admission, programme midpoint, or at the end of the programme) and levels also contribute to programme level assessment. In some ODeL institutions, selected assignments are re-scored (second reading) by programme faculty to assess the general education programme’s success in achieving institutional goals, such as communication skills, critical thinking, and ethical responsibility, among others.

Finally, institutional level assessment is undertaken either for improvement of internal operations and management (i.e. resource allocation, faculty hiring, faculty and staff development, collaborating, and networking) or fulfilment of external accountabilities. Results of the former can often also serve the latter purpose. According to Morgan and Taschereau (1996), assessment at this level is a comprehensive approach for profiling institutional capacity and performance as various factors come into play in this level of assessment. These factors are: 1) “the forces in the external environment (administrative and legal, political and economic, social and cultural)”; 2) “institutional factors (history and mission, culture, leadership, structures, human and financial resources, formal and informal management systems, and an assessment of performance)”; and 3) “inter-institutional linkages” (Morgan & Taschereau, 1996).

At institutional level assessment, a significant body of evidence coming from multiple sources are necessary to address questions such as: “What do the institution’s academic programmes add up to in terms of student learning?,” “How well are the goals and outcomes for student learning achieved?,” and “How can institutional effectiveness be reported to the external stakeholders?” (Miller & Leskes, 2005).

These evidence can come in the form of documentation that show how well the students are meeting institution-wide goals. Summarized data aggregated by course, by programme, or by student cohort, supplemented by results from relevant exams (admissions exam, licensure, etc.) would largely contribute to the institution-wide assessment. Hence it is important for institutional leaders to work in close collaboration with the faculty and staff, student affairs, and other professionals when designing a comprehensive programme of institutional assessment that address the following concerns: 1) the mechanisms being used to gather evidence of student learning and to provide feedback to students; and 2) the system of communication made to provide students’ access to needed resources and others.

Assessments in ODeL are no less valid and reliable than assessments in the traditional setting. The assessment instruments are expected to be appropriate and the criteria clearly defined and capable of generating evidence for the objectives and outcomes to be assessed. However, identifying or creating assessment tools for O-DeL can be quite challenging, considering that assessors are not in direct contact with the student whose performance is the most valid method of assessment. To ensure the reliability of the flexible learning provision of ODeL, assessment decisions must be as consistent as possible, subject to some internal checking, both in the course and programme levels. Moreover, appropriate training of the people involved in the assessment should be required (SQA, 2000). Support for student assessments should also integrate a variety of approaches such as flexipacks, scheduled tutorials, electronic-support modes, tutor-marked assignments, supervised workplace, or testing center assessments. With the introduction of information and communications technology (ICT) to student assessment, flexible learning programmes, which involve educators from both the conventional and ODeL modes, find enhanced flexibility, authentication, and security. Issues on communication, delivery, and administration, are also addressed. However, the concern with flexible learning environments is it has been constantly changing and responding to global initiatives and the advances in technology.

Quality has always been a concern of higher education institutions. UNESCO (1998) has referred to quality in higher education as a “multi-dimensional concept” that encompasses all academic functions and services ranging from “teaching and academic programmes, research and scholarship, staffing, students, facilities, faculties, and services to the community and the academic environment”.

Quality assurance in higher education, on the other hand, has been characterized as a continuous improvement of academic processes. It is the means towards assessing the potential of educational institutions in effectively performing and delivering these functions and services (Friend-Pereira, Lutz, & Heerens, n.d). Conducted either through internal self-evaluation or an external review body (UNESCO, 1998), quality assurance uses a set of agreed upon standards which may vary in terms of scope, depth, emphasis, and review components (Southard & Mooney, 2015).

In the literature, several quality assurance frameworks have been articulated. Often, these are associated with assessment and accreditation. Currently, there are several accrediting bodies, institutes, consortiums, and trade associations established especially for distance learning in higher education worldwide (Southard & Mooney, 2015). With the common goal of ensuring quality in distance education, they take initiatives in developing sets of standards, criteria, guidelines, or benchmarks which can address the uniqueness brought about by distance education in higher education.

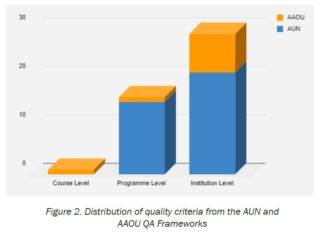

For higher education institutions in the ASEAN context, the ASEAN University Network (AUN) developed the AUN-Quality Assurance Framework which focuses on assessment at the programme and institutional levels (ASEAN University Network, 2016). Programme level assessment constitutes a total of 15 criteria which include: Expected Learning Outcomes; Programme Specifications; Programme Structure and Content; Teaching and Learning Strategy; Student Assessment;Academic Staff Quality; Support Staff Quality; Student Quality; Student Advice and Support; Facilities and Infrastructure; Quality Assurance of Teaching and Learning Process; Staff Development Activities; Stakeholders Feedback; Output; and Stakeholders Satisfaction. Institutional level assessment, on the other hand, constitutes a total of 22 criteria which include the following: Vision, Mission, and Culture; Governance; Leadership and Management; Strategic Management; Policies for Education, Research, and Service; Human Resources Management; Financial & Physical Resources Management; External Relations & Networks; Internal Quality Assurance System; Internal & External QA Assessment; IQA Information Management; Quality Enhancement; Student Recruitment and Admission; Curriculum Design and Review; Teaching and Learning; Student Assessment; Student Services and Support; Research Management; Intellectual Property Management; Research Collaboration and Partnerships; and Community Engagement and Service.

In the field of open and distance learning, the Asian Association of Open Universities (AAOU) Quality Assurance Framework has been developed (Belawati & Zuhairi, 2007; Darojat, et al, 2015). The framework sets out important guidelines for each of the ten strategic issues identified in the distance education system: Policy and Planning; Internal Management; Learners and Learners’ Profiles; Infrastructure, Media, and Learning Resources; Learner Assessment and Evaluation; Research and Community Services; Human Resources; Learner Support; Programme Design and Curriculum Development; and Course Design and Development.

A cursory glance at these existing quality criteria shows that there are obvious commonalities and overlaps when categorized along the levels of assessment (Figure 2). Most quality assessment criteria are concentrated at the institutional level suggesting the importance of institutional leadership and the organization’s commitment to ensuring quality.

And while these have been shown to be sufficient for most teaching and learning situations, the evolution of higher education institutions coupled with technological advances highlights the need for quality considerations appropriate in a networked and digital environment.

With the changing concept of higher education, new conditions and structures have been introduced in teaching and learning. In distance education, Kanwar (2013) observed that quality standards got refocused to course preparation, quality of materials, assessment in the form of feedback and interactivity from earlier emphasis on faculty, infrastructure and facilities, entry requirements, prescribed curriculum, attendance and evaluation procedures to assess the institution’s performance. Moreover, with the emergence of information and communication technologies in the 1990s, these quality standards were once again refined resulting from personalization and interactivity features of distance education.

Faculty role, course management, coursework, and even library and learning resources in distance education could be entirely different from traditional education, as the former makes use of and requires more electronic access than the latter (Stella & Gnanam, 2004). As a result, this range of new conditions presented by distance education has cast doubts on the validity of existing quality assurance systems in higher education. While there are those who argue that distance education is already being considered as a long established form of higher education and thus can be treated just the same as traditional education, there are also those who assert that with the uniqueness in its mode of educational delivery, distance education might find existing quality assurance mechanisms insufficient (Stella & Gnanam, 2004).

In the case of an ODeL institution, the affordances of open learning, distance education, and e-learning bring to the fore the need to include the influence of the technology dimension in a quality assessment framework. Further, we venture to say that these have to be incorporated at all levels of assessment.

To get an indication of the inclusion of such dimension, we reviewed the existing quality assessment criteria by locating the words “access and equity,” “resource sharing,” “learner-centeredness,” “flexibility,” “active learning,” “interactivity,” “ubiquity,” and “connectivity” in their descriptions. Initial appreciation of the results reveal that these affordances are present to some extent in the various criteria and across assessment levels. The affordances related to access and equity, resource sharing, learner-centeredness, flexibility, and active learning are reflected in quality criteria at programme and institution levels. Interactivity, ubiquity, and connectivity, which are associated with e-learning as in the ODeL framework (see Figure 1), have not been found to be explicitly reflected in the criteria we examined.

Indicative of these initial results is a need for greater focus to be given to the influence of technology on quality assessment criteria at course, programme, and institution levels. As technology permeates all levels of assessment, more so in an ODeL context, it is proposed that future quality assessment framework development include the potential influence of technological affordances.

Alfonso, G.J.A., & Garcia, P.G. (2015). Open and distance eLearning: New dimensions in teaching, learning, research, and extension for higher education institutions. International Journal on Open and Distance eLearning, 1(1-2). Retrieved from http://ijodel.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/001_Alfonso_Garcia.pdf

Alverno College. (n.d.). Student assessment as learning. Retrieved from depts.alverno.edu/saal/essentials.html

ASEAN University Network. (2016). Guide to AUN-QA assessment at institutional level. Retrieved from http://aunsec.org/pdf/Guide%20to%20AUNQA%20Assessment%20at%20Institutional%20Level%20Version2.0_Final_for_publishing_2016%20(1).pdf

Asian Association of Open Universities. (2017). Asian Association of Open Universities. Retrieved from http://aaou.upou.edu.ph/

Barrette, C. Program Assessment: Purposes, Benefits and Processes [PDF document]. Retrieved from https://wayne.edu/assessment/files/1_introduction_to_program_assessment.pdf

Baume, D., & Yorke M. (2010). The reliability of assessment by portfolio on a course to develop and accredit teachers in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 27 (1). Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03075070120099340

Belawati, T., & Zuhairi, A. (2007). The practice of a quality assurance system in open and distance learning: A case study at Universitas Terbuka Indonesia (the Indonesia Open University). International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 8 (1). Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1634488781?accountid=47253

Brookhart, S.M. (2010). Formative assessment strategies for every classroom: An ASCD action tool (2nd ed). Alexandria, VA: USA.

Carey, J. O., & Gregory, V. L. (2003). Toward improving student learning: Policy issues and design structures in course-level outcomes assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28 (3), 215-227.

Cîrneanu, N., Chiriţă, M., & Cîrneanu, A. (2009). The quality of the educational services offered by the military organization. Revista Academiei Fortelor Terestre, 14(4), 7-12. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/ 89154071

Darojat, O., Nilson, M., & Kaufman, D. (2015). Quality assurance in Asian open and distance learning: policies and implementation. Journal of Learning for Development, 2 (2). Retrieved from http://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/105/96

Dellwo, D. R. (2010). Course assessment using multi-stage pre/post testing and the components of normalized change. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10 (1), 55-67. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ882126

Dochy, F., Sergers, M., & Sluijsmans, D. (1999). The use of self-, peer and co-assessment in higher education: A review. Studies in Higher Education. 24 (3). 331- 350. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline. com/doi/abs/10.1080/03075079912331379935

Friend-Pereira, J.C., Lutz, K., & Heerens, N. (n.d.) European Student Handbook on Quality Assurance in Higher Education. Retrieved from ttp://www.aic.lv/bolona/Bologna/contrib/ESIB/QAhandbook.pdf

Jamornmann, U. (2004). Techniques for assessing students’ elearning achievement. International Journal of The Computer, the Internet and Management, 12(2). Retrieved from http://www.ijcim.th.org/ past_editions/2004V12N2(SP)/pdf/p26-31-Utumporn-Techniques_ for_assessing-newver.pdf

Johri, A. (2006). Interpersonal assessment: Evaluating others in online learning environments. In Roberts, T. S. (Ed.). Self, Peer, and Group Assessment in E-Learning. 259-278. Retrieved from http://go. galegroup.com/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=T003&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&searchType=BasicSearchForm¤tPosition=13&docId=GALE%7CCX2581700018&docType=Topic+ overview&sort=RELEVANCE&contentSegment=&prodId=GVRL&contentSet=GALE%7CCX2581700018&searchId=R5&userGroupName=phupou&inPS=true

Kanwar, A. (2013). Foreword. In Jung, I. Wong, T.M. & Belawati, T. (eds.), Quality assurance in distance education and elearning: Challenges and solutions from Asia, pp. xxi – xxiv. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

Keegan, D. (1980). On defining distance education. Distance Education, 1(2), 13-36.

Maki, P.L. (2004). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Stylus Publishing LLC. Sterling, Virginia: USA

Miller, R. & Leskes, A. (2005). Levels of assessment: From the student to the institution. Association of American Colleges and Universities. Washington DC: USA

Morgan, P. & Taschereau, S. (1996). Capacity and institutional assessment: Frameworks, methods and tools for analysis. Canadian International Development Agency. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.119.7536&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Rahman, H & Ramos, I. (Eds.) (2003). Ethical Data Mining Applications for Socio-Economic Development. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Reisberg, L. (2010). Quality assurance in higher education: Defining, measuring, improving it. Retrieved from http://www.gr.unicamp.br/ceav/pdf/unicamp_qa_day1_final[1].pdf

Scottish Qualifications Authority. (2000). Assessment and quality assurance in open and distance learning. Hanover House, Glasgow: UK

Silva, M. L., Delaney, S. A., Cochran, J., Jackson, R., & Olivares C. (2015). Institutional assessment and the integrative core curriculum: Involving students in the development of an ePortfolio system. International Journal of ePortfolio, 5 (2), pp 155-167. Retrieved from https://eric. ed.gov/?id=EJ1107858

Southard, S. & Mooney, M. (2015). A comparative analysis of distance education quality assurance standards. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 16 (1), pp 55-68.

Stella, A. & Gnanam, A. (2004). Quality assurance in distance education: The challenges to be addressed. Higher Education, 143-160.

Suzuki, L.A., Kugler J., & Ahluwalia M.K., (2005). Teacher assessment. In Farenga S.J. & Ness, D. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Education and Human Development. 106-109. Retrieved from <http://go.galegroup.com/ps/retrieve.do tabID=T003&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&searchType=BasicSearchForm¤tPosition=6&docId=GALE%7CCX2652800043&docType=Chapter+topic&sort=RELEVANCE&contentSegment=&prodId=GVRL&contentSet=GALE%7CCX2652800043&searchId=R5&userGroupName=phupou&inPS=true>

UNESCO. (1998). World declaration on higher education for the twenty-first century: Vision and action. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/educprog/wche/declaration_eng.htm

University of Central Florida. (2008). Program assessment handbook: Guidelines for planning and implementing of program and student learning outcomes. Retrieved from https://oeas.ucf.edu/doc/acad_assess_handbook.pdf

Lumanta, M. F. and Carascal, L. C. (2018). Towards an Assessment Framework for ODeL: Surfacing Quality Dimensions. In M. F. Lumanta, & L. C. Carascal (Eds.), Assessment Praxis in Open and Distance e-Learning: Thoughts and Practices in UPOU (pp. 179-191). Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines: UP Open University