The colloquium, as a class format, has been widely used in graduate programs where experts present their views on a specific topic normally held in a class setting where face-to-face interaction can be observed and monitored. This chapter is an exploratory study that assessed student interaction in an online graduate colloquium class. It used a combined methodology of applying network analysis that looks into the interaction patterns and a self-report questionnaire on the students’ preparedness for an online colloquium course, their role as moderator and participant in the colloquium, and their perceived overall usefulness of the colloquium approach.

The use of the colloquium as a class format has long been used in residential learning. In the field of open and distance e-Learning (ODeL), however, use of this pedagogical approach which maximizes peer interaction among learners is yet to be explored.

In an article published in 2006 by the Capella University, the colloquia philosophy and how it is seen as an effective approach when incorporated in the doctoral program was presented. The article, titled “The Colloquia Philosophy: Scaffolding for a Transformative Learning Experience,” discussed how doctoral learner motivation changes as the learner progresses through Tinto’s three stages of development (Rose, 2005). The first stage centers mainly on developing a connection with colleagues, faculty, and support resources; the second stage concentrates on acquiring academic skills needed particularly for coursework and comprehensive examination; and the third stage focuses on designing and completing the dissertation research. These three stages are bridged by the colloquia learning experience “through an organized curriculum that recognizes the developmental aspect of the doctoral education experience” (Capella University, 2006).

As this colloquium class format is still new in ODeL, studies on how this pedagogical approach can be further developed need to be conducted for ODeL institutions to maximize its potential. This exploratory study aimed to assess student interaction in an online colloquium class that was intended to prepare doctoral students for their research-based dissertation. This was done by using a combined methodology of applying network analysis that maps the interaction patterns among the participants of the course and a self-report questionnaire that measured the graduate students’ preparedness for an online colloquium, their assessment of their experiences in playing both moderator and participant roles in the colloquium, and perceived overall usefulness of the colloquium approach.

In the Doctor of Communication Program of the UP Open University, students are required to take a course wherein they participate in a student-managed online colloquium. The course, titled ‘Colloquium on Communication Research,’ requires that the students complete a theory and practice course and research methods courses. The course on colloquium is the last course taken by the students prior to the conduct of their dissertation.

Being online, student-led, and a culminating course elevates expectations of the Doctor of Communication Program as it hopes to address knowledge acquisition, critical thinking, and skills development through a collegial exchange of ideas. As colloquium members, the students are assigned two roles – as moderators/lead discussants/resource persons and as participants. At the beginning of the course, students select and propose a specific seminar topic that she or he shall plan and implement during the rest of the semester. As this is a colloquium on communication research, topics are expected to focus on research tools, methods, approaches, issues, and practices that are relevant to the students’ research topics. Each student is then given a week to be a moderator/lead discussant/ resource person; while for the rest of the semester, she or he will be as participant in she or he colleagues’ colloquia.

On one hand, as a moderator/lead discussant/resource person, the student is expected to make a presentation and propose issues for discussion; hence the students have to choose a topic that they are familiar with to allow them to articulate the topic of interest and identify the most relevant research issues. As participant, on the other hand, the student provides insights and comments on their colleagues’ topic presentations. Each colloquium block is capped off by a written documentation of the interactions in the session which the student moderated. The online colloquium class is presented in Figure 1.

The emergence of distance education introduced a new perspective on how interaction in a learning situation occurs. Anderson (2003) identifies student interaction, teacher interaction, and content interaction as the three modes of interaction in distance education. He states that:

“Deep and meaningful formal learning is supported as long as one of the three forms of interaction (student–teacher; student- student; student-content) is at a high level. The other two may be offered at minimal levels, or even eliminated, without degrading the educational experience.” (Anderson, 2003; par. 11)

The online colloquium course investigated in this chapter was designed with increased level of student-student interaction, and minimal student- teacher interaction, it being student-led and managed. Student-content interaction was ensured as relevant reading materials were introduced by the moderator at the beginning of a colloquium block. The student’s role as both moderator and participant in the course was introduced to increase learning through a community of learners, a distinctive feature of online education. De Schutter, Fahmi, & Rudolph (2004), through a thorough literature review, explored the role of the moderator in making an online discussion productive. In their article, they discuss the importance of the moderator when it comes to encouraging the following activities:

- Participant access and motivation. Participant’s access to and knowledge about software is a pressing factor in making an online conference productive (De Schutter et al., 2004). Moderators need to provide participants with enough information (i.e., agenda and objectives of the conference, description of what is expected of the participants, an outline of recommended pre-readings, and preparatory materials) to enable them to participate effectively in the conference. De Schutter and colleagues (2004) also emphasize the need for an online conference moderator to know how to balance between the two approaches to conference moderation which are: the facilitatory approach (encouraging exchange of experiences among the participants) and guided approach (occasional steering and re-focusing of discussion).

- Online socialization. Putting the participants at ease while promoting social interaction among them is imperative in creating a learning environment through online conferencing. These could be achieved by the moderator through a number of strategies, such as personally welcoming them or asking everyone to introduce themselves (De Schutter et al, 2004; Green, 1998). It is also important for moderators and participants to practice “netiquette” (De Schutter et al, 2004; Green, 1998) in which they respect others’ opinions, beliefs, and values; not dominate the discussion; and encourage and acknowledge others’ contributions.

- Information exchange. An “asynchronous, educational, text-based conference” (De Schutter et al, 2004; Green, 1998) should have a number of participants ranging from 10 to 15. Furthermore, ensuring that these participants are given access to technology which enables them to share information that’s not just about the course, but also about using the technology, is recommended (Salmon, 2002, as cited by De Schutter, et al, 2004).

- Knowledge construction. The moderator is also expected to encourage discussion by asking open-ended and thought-provoking questions (Green 1998, as cited by De Schutter et al, 2004), summarizing the content of the discussion and the contributions of the participants, and eliciting feedback about the content and process of the online conference (De Schutter et al, 2004). The moderator, responsible in stimulating participants’ interest and encouraging discussion among them, should be provided access to a tool that allows her or him to track student participation. She or he should also have access to relevant materials (i.e., details of the conference objectives, relevant text passages, definitions, illustrations, references, and hyperlinks) which can be “cut and pasted” into the conference text box at appropriate moments. In the case of the online colloquium course being explored in this study, all the students were able to take on the role of a moderator. Hence the investigators looked into the nature of interaction among the colloquium participants through a network study. This was supplemented by a perception survey to determine the students’ experiences in performing both the moderator and participant roles in the colloquium.

Cadoc-Reyes (2012) explains how cognitive interpretation, which happens when learners exchange information with peers, leads to the “internalization, modification, objection, or further reification of information.” Accordingly, sharing and exchanging of resources, posing challenging questions, and giving constructive feedback among peers (Yang, Yeh, and Wong, 2010, as cited by Kuboni, 2013) could be best attained when both the instructor and learner innovate in terms of monitoring individual and group performance and “knowledge sharing in virtual classroom discussion forums.”

Network studies are used to analyze relationships and interactions in the social system of an online classroom. Studies have shown that social networks greatly influence the flow and process of knowledge generation in online learning communities (Wang & Li, 2007). According to Knoke & Yang (2008), “a social network is a structure composed of a set of actors, some of whose members are connected by a set of one or more relations.” Based on the assumption of network theory that focuses on the interaction and relationship of individuals in a given system, social network analysis is popular in viewing patterns of ties among “nodes” or actors and how these patterns affect the relationship among individuals in a given system or network. These ties and nodes could be depicted through a sociogram: a visual representation that could be automatically generated through softwares like UCINET, Pajek, ORA, GUESS, and Cytoscape.

A number of social network metrics is used in network analysis to determine the degree of influence a network and its actors demonstrate. Hanneman and Riddle (2005) and Knoke and Yang (2008) describe these metrics as follows:

● Betweenness. Betweenness views the social network in a micro level. It looks into how pairs of actors are connected through an actor that lies between them. These actors, called the “bridge,” are in an advantageous position as they connect two active nodes and their absence would result in an end to the connection between the two nodes. Basically, betweenness determines the number of “information paths” an actor has and who connects different groups of nodes in the network (Gruzd, 2016).

● Closeness. Closeness also views the social network in a micro level. However, unlike betweenness, closeness determines the length of path an actor has from the rest of the actors. According to Hanneman & Riddle (2005), the actors who are in an advantageous position are those “who have shorter path lengths from other actors, or those who are more reachable by other actors at shorter path lengths.”

● Degree Centrality. Degree centrality also views the social network in a micro level. It measures the number of ties each actor has in a network and is distinguished based on “in-degree” and “out-degree” measures. An actor who receives many ties (in-degree) are usually called “prominent” or actors with “high prestige” (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005); while actors who demonstrate high out-degree measures are called “influential actors.”

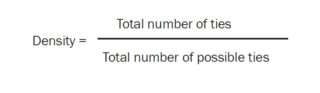

● Network density. Network density views the social network in a macro level. It indicates the “overall connectivity” in the network (Gruzd, 2016) by measuring the strength of the ties which are present in the network over the number of possible ties in the same network (Knoke and Yang, 2008). Low density indicates that not much power is exerted in the network, while high density means that the network has potential for greater power (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). The denser a network is, the higher the connection within the network. Hence a denser network has greater potential in exhibiting higher information flow among actors. The formula for density is as follows:

The study focused on the online colloquium course which had a total of 15 enrolled students. Two sources of data were used. The first was the conversation threads in the students’ colloquia wherein interaction among the students were plotted and analyzed using the UCINET software. In particular, the network’s properties (degree centrality and density) were determined to analyze student interaction in all of the fifteen colloquium blocks.

The second data source was a three-part survey questionnaire which aimed to determine the students’ perception on the usefulness of the online colloquium in preparing them for their dissertation. Of the 15 students enrolled in the course, 14 answered the questionnaire. The researchers attempted to analyze the two roles (moderator and participant) performed by each student through a set of 16 questions presented in a Likert-type perception survey: the first part determining the students’ perspectives as moderators of their own colloquium and the second part determining the students’ perspectives as participants in their colleagues’ colloquia. A third part consisting of a Likert-type question also measured the degree to which the overall design of the course has helped prepare the students for their dissertation. This was followed by an open-ended question asking the students to explain their answer to the third part of the survey.

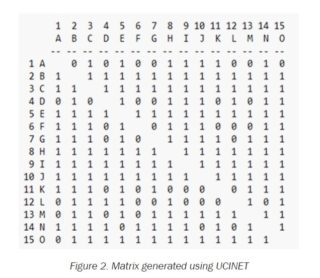

The UCINET software was used to determine the colloquium network’s degree centrality and network density. For the perception survey, frequency distributions and measures of central tendency were used to describe the students’ answers. Likert-type questions categorized under De Schutter and colleagues (2004) four categories (participant access and motivation, online socialization, information exchange, and knowledge construction) were presented in the first and second part of the questionnaire. Code numbers one (1) to five (5) were used for the variables being measured wherein the higher score (5) indicates a stronger agreement to the variable being scaled. Means of parameters were obtained to interpret the level of agreement using Likert-type scale with equivalent rating measurements. The interaction of students was mapped through the use of UCINET software wherein a sociogram illustrates the ties and connection in the network. Figure 2 presents the matrix table which was generated to analyze the presence and absence of ties among the students and the density of the colloquium network. A value of “1” indicates presence of ties, otherwise, no tie was observed. A total of 169 actual ties was observed.

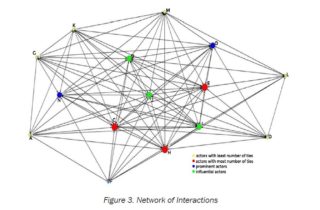

In general, the value of network density observed was 0.80 or 80% of all the possible ties present in the network. The higher the network density, the stronger the connection among the actors in the network which also indicates that the information exchanges in the network was high and that students were able to actively exchange and share information with each other. Figure 3 illustrates the interaction of the students who participated in the colloquium. It shows actors C, H, and E (in red) as the actors with the most number of ties in the network. Measuring the in-degrees and out-degrees of each actor in the network, actors C, H, and E were identified to be possessing the highest number of both in and out degree measures, hence, they are considered as the actors who played an important role in sharing and receiving information in the network. In addition, actors N and O (in blue) are seen to have a significant in-degree values, making them the prominent actors in the network; whereas actors B, I, and J (in green) are noted to have high out degree values which implies that these actors are the influential actors in the network.

The first and second parts of the questionnaire used a Likert-type scale to measure the students’ level of agreement on how the online colloquium course helped them as both colloquium moderators and participants. Results indicated a high score on De Schutter and colleagues’ (2004) four categories: participant access and motivation; online socialization; information exchange; knowledge construction, with the first category getting the highest score of 4.41. These results were supported by the students’ answers in the open-ended portion where most answers fell under the knowledge construction and participant access and motivation categories. On the question measuring the degree to which the overall design of the course in a colloquium format has helped the students prepare for their dissertation, a mean score of 4.43 was generated; indicating that the online colloquium course was perceived by the students as very helpful in preparing them for their dissertation.

With the use of a combined methodology of applying network analysis and self-report questionnaire, the results indicate that indeed a pedagogical approach that maximizes interaction among learners in an online learning community positively contributes to knowledge construction. The mapped interactions in the online colloquium revealed that its network density is high, implying that there is a strong connection among the students which enabled them to actively share and exchange information among themselves. This leads to knowledge construction which is at the core of a doctoral research or dissertation and the end-goal of a colloquia approach as a developmental process.

Anderson, T., & Garrison, D.R. (1998). Learning in a networked world: New roles and responsibilities. In C. Gibson (Ed.), Distance Learners in Higher Education. (pp. 97-112). Madison, WI: Atwood Publishing.

Borgatti, S.P., Everett, M.G. & Freeman, L.C. (2002). UCINET 6 for Windows: Software for social network analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

Brown, A.R. & Voltz, B.D. (2005). Elements of effective e-learning design. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 6(1). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/ irrodl/article/view/217/300

Cadoc-Reyes, J. (2012). Learners’ heterogeneity and knowledge sharing in cooperative e-learning. ASEAN Journal of Open and Distance Learning, 4(1). Retrieved from http://ajodl.oum.edu.my/sites/default/files/document/vol4-no1/Vol4-02.pdf

Capella University. (2006). The Colloquia Philosophy: Scaffolding for a Transformative Learning Experience. Retrieved from http://docplayer.net/20749678-The-colloquia-philosophy-scaffolding-for-a-transformative-learning-experience.html

De Schutter, A., Fahrni, P., & Rudolph, J. (2004). Best practices in online conference moderation. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 5(1). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/164/245

Green, L. (1998). Playing croquet with flamingos: A guide to moderating online conferences. Human Resources Development Canada. Retrieved from: http://archive.org./stream/ERIC_ED433014/ERIC_433014_djvu.text

Gruzd, A. (2016). Learning analytics for the social media age: Studying online interaction using social network analysis [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved from: www.ouhk.edu.hk/URC/LA3_workshop.pdf

Hanneman, R.A. & Riddle, M. (2005). Introduction to social network methods. Riverside, CA: University of California, Riverside (published in digital form at http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/)

Higgins, C. & Face, C.M.J. (1998). Integrating information literacy skills into the university colloquium: Innovation at Southern Oregon University. Reference Services Review, 26(3-4), 17-31.

Latif, L.A, Bahroom, R. & San, N.M. (2009). Skills, usage, and perception of ICT and their impact on e-learning in an open and distance learning institution. ASEAN Journal of Open and Distance Learning, 1(1). Retrieved from http://ajodl.oum.edu.my/sites/default/files/document/

vol1-no1-2009/Vol1-08.pdf

Kehrwald, B. (2007). The ties that bind: Social presence, relations and productive collaboration in online learning environments. In ICT: Providing choices for learners and learning. Proceedings ascilite Singapore 2007. http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/singapore07/

procs/kehrwald.pdf

Knoke, D. & Yang, S. (2008). Social network analysis (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publication, Inc.

Kuboni, O. (2013). The preferred learning modes of online graduate students. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1462/2603

Rose, G. L. (2005). Group differences in graduate students’ concepts of the ideal mentor. Research in Higher Education, 46(1), 53-80.

Salmon, G. (2002). Five-step model of teaching and learning online. Retrieved from www.uws.edu.au/_data/assets/pdf_file0003145183/emoderating.pdf

Wang, Y. & Li, X. (2007). Social network analysis of interaction in online learning communities. Advanced Learning Technologies, IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, pp.699-700

Yang, Y-F., Yeh, H-C ., & Wong, W-K. (2010). The influence of social interaction on meaning construction in a virtual community. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 287-306.

Lumanta M. F., Dolom M. A. C. , & Perez, J. J. E. (2018). Network Analysis in Assessing Interaction in an Online Colloquium Course. In M. F. Lumanta, & L. C. Carascal (Eds.), Assessment Praxis in Open and Distance e-Learning: Thoughts and Practices in UPOU (pp. 139-151). Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines: UP Open University